.png?width=860&height=430&name=260%20GMDP-header%20(1).png)

Most people in the world of Medical Devices know that they need a Quality Management System (QMS), but what is the best way to go about building that QMS, when should you start, and how do you know when you've built it to the point it can stand on this own?

In this episode, Rob MacCuspie, PhD, Manager of Regulatory and Quality Affairs at Proxima Clinical Research, Inc., discusses the best practices of companies he has worked with to help implement their Quality Management System in a manageable way.

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some of the highlights of this episode include:

- What is the difference in your QMS and a Document Management System?

- What is the most important aspect of a QMS?

- Who really needs a QMS, and when?

- What are the phases of a QMS?

- How to start building a QMS.

Links:

- Rob MacCuspie on LinkedIn

- Etienne Nichols on LinkedIn

- Proxima Clinical Research

- Greenlight Guru software

Memorable quotes:

""If my SOPs and training process can bring in somebody that has no experience and they can hit the ground running, I'm not worried if the auditor has any experience now in my space, right. Because I now have everything in place to show somebody how they can teach themselves and learn and get up to speed and walk through the process."

Transcript

Etienne Nichols: Hey everyone. Welcome back to the Global Medical Device Podcast.

I'm the host of today's episode. My name is Etienne Nichols and today with me is Rob MacCuspie from Proxima Clinical Research. So glad to have you back on the show Rob.

Rob MacCuspie: Great to be here, thanks for having me back.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I'm excited about today's topic because this is one know, we talk a little bit about every now and then. We don't always take the subject head on, but that is quality management systems, what is it, when do you implement it, who is this for?

And so forth. So, I really appreciate this topic, and I wonder if you want to introduce it a little bit better. I know you have a lot of thoughts and different points you want to cover, but I'll go ahead and let you talk to, well first maybe a little of your background and then we can jump into the topic itself.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, sure.

So, I started out as a PhD bench chemist in the National Lab System and did a brief stint in academia before getting intrigued by the medical device industry. And I've been in the industry for about eight years now and have done everything from R&D, new product development, director of labs, product education and I kept getting drawn into the regulatory and the quality side and was really fascinated by it working in the various startups and small businesses.

And so, a couple of years ago had the opportunity to join Proxima Clinical Research and really scale my efforts and be a part of a lot of teams and so really loving it and love working with folks that are bringing new products to market.

Etienne Nichols: And for those of you who listen pretty regularly, you probably heard Robin, my episode last week not last week, last fall I believe it was. So, we were trying to figure out exactly when that was.

I'll have to go back and put a link in the show notes if you want to hear his previous episode, but he has a lot of great experience in this industry. It's more about the mileage than it is the years it seems like. And working with Proxima, I know you see so many companies and get to kind of look at different best practices along the way.

So, I really appreciate you coming on the show and kind of talking through some of these things. Do you want to go ahead and talk maybe we can start out with what is a quality management system, and we can maybe start there.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, so a quality management system is really the overall set of documentation and processes that are going to ensure that the product has acceptable quality. And it's always safe and it's always effective for every single patient or customer that uses the device.

And so, there's a lot of care that people put into designing and engineering these devices. And a lot of that is documenting, how do we do that? How do we do that?

Well, why did we make those decisions?

Why did we set these specifications this way? Why did we design it this way? And then all of that effort that the engineering and design team has put into it; we want to transfer that to the manufacturing team because they want to make it the same way every time.

And they want to know, okay, is this like a three-lane highway that I have to stay within, or is this like a narrow, winding mountain road? I got to be super careful.

And so, they don't know they didn't do the design. They just want to follow that. And so, there's the tech transfer aspect and the manufacturing, and then there's the post market surveillance of wanting to know, hey, what's the customer feedback?

Does anyone have anything that happened that we need to know about and want to know about? And then that way it allows this process of continuous improvement as well, so that you can continue to improve the device and make the next generation make the next great innovation.

Oh, yeah, it's the law. We have to follow the code of federal regulations. 21 CFRA 20 says we have to have one. So, yeah, that's another good reason.

Etienne Nichols: Absolutely. Yeah. And when I first came to MedTech so many moons ago, I wish that I'd had that illustration that you talked about. Are we on a three-lane highway or are we on a windy mountain road?

I've talked about this in the past. The FDA is not going to specify the speed limit. It just tells you the curves, the radius of the curve, the angle, the friction coefficient of the gravel or whatever. And you decide based on what you're driving, Class 3, device, Class 1, so forth, how fast you need to go, and so forth.

So, I think that's a really good illustration. I like that you use that.

So, I'm curious if you want to talk maybe a little bit more. You mentioned it's the legal requirement, and we talk about ISO 1345, part 820 as well. And of course, for those of you keeping up with the legal requirements, there's QMSR and the harmonization with ISO 1345. So, it's more important than ever to be thinking on a global scale.

So, when we're building out a quality management system, there's lots of different questions we could ask, and one of them that we get asked a lot is when do I need to start?

Do you want to mention or kind of talk to that question?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, that's a great question. And this is one that comes up with a lot of our clients.

All right. We love it when we get to work on our partnership. And folks are like, okay, we've already got this great eQMS with Greenlight Guru, so can you help us navigate it? There's kind of two perspectives I see in when do I start. There's the investor perspective of, well, let's delay the cost as long as possible and just push it out and just at the last possible second have anything.

And then there's this FDA perspective.

Know innovators are going to have their quality management system in place, have most of the effort done, and then they're going to start their regulatory interactions. And so, there's this balance because if something's not written down and documented in a quality management system, it didn't happen in the eyes of the regulators.

And so, you can choose to do all of this development, but it's kind of like still the back of the napkin stage in a lot of ways because you don't have anything real yet.

So, a lot of times I encourage CEOs or investors, well, how long do you want us to go without actually having a real product? Because there needs to get to a point where we're going to have a real product.

Right?

Etienne Nichols: Right.

Rob MacCuspie: And so that kind of helps find where is that balance? Because obviously sketching on the back of napkin. You don't need a fully built out QMS yet, but you do want to have documentation of, hey, look, we thought about these different design constraints like we were talking about earlier with the analogy. Do we need a three-lane superhighway each way, like an interstate highway, or can we have a winding road that hugs the grade of the terrain?

And both are right for different situations, right? And so, it's kind of looking through what are the user needs? Why are we making this device in the first place? What problem is it going to solve?

And then going into a way to document all of that as you go through the process. So, you want to capture all of that great work that's going into it and really be able to take credit for it.

Etienne Nichols: So, there's a couple of things that I think of, too, when I think of when to start a quality management system. And you kind of touched on this, and I wonder if maybe you could elaborate, but let me kind of develop this thought.

There’re multiple perspectives you have when you're building out a company or when you're growing your company or growing your product portfolio, you have the perspective of the legal, the regulatory requirement.

So, there's a hard line you have to start here. And maybe we can talk about when that hard line is oftentimes when we ask about hard lines. It depends. And that's a fair answer.

We can maybe talk about through those different caveats, but then there's a different perspective. Besides the regulatory requirement and the legal requirement as a business, there's also the safety and ethical requirements. So, what could build the safest and the most ethically sound product? And then there's the third. That's the monetary I look at companies, medical device companies, especially as having three legs.

You have the regulatory legal requirement; you have the safety and ethical requirement. Oftentimes those overlap. They don't always. And then there's the third one, and that's making money, the economical requirement.

And that's really you look at a quality management system, we think, oh, this is specific to medical device. But ISO 1345, you look in the back, it compares to ISO 9001, right, which is one of the goals is to have best practices for the industry.

So, I kind of said a lot there. Thank you for listening to my Ted Talk. I wonder if you could kind of expound a little bit on what perspective are we looking at this, when to start a quality management system and the different thought processes you go through as you look through those different lenses.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, so I tend to look at it as earlier is better. And then there's also kind of this idea of making a plan from the beginning of we don't have to build everything all at once.

Right.

That's very common in the start world. Like, we're not going to go to scaling up manufacturing when we're still working out the details of the device. Right. There’re stages that we go through to hit those different milestones.

And so similarly, the QMS, you can build it just in time and say, okay, we're going to have the early stages, like our document control and design controls when we're doing the design phases.

And we can put off some of that manufacturing till we get there. Then when we get to manufacturing, we can still put off some of that post market surveillance type questions to when we get a little bit closer to that stage.

So, you can kind of build it in stages so it's kind of delivered just in time as you go through. And so that way it allows to capture.

For me, it's really about capturing the work and not having to repeat things because that's something that nobody likes, having to do the same thing twice. And there's the joke, like there's never enough time to do it the first time.

There's always enough time to do it right the second time.

So, for me, it's like, well, you want to be able to show we thought about this, and it's okay if it's not perfect the first time. A lot of times auditors will say, hey, that shows that you looked at it and then refined it based on that.

It shows that continuous improvement is baked into the culture. So, from the legal side as well. There's that consideration of, okay, I don't necessarily have to show my QMS to the FDA to get A.

They're not going to come in and inspect it. But the day I've got that 510(k) clearance and I start selling, an auditor can knock on the door and ask to look back at all those records.

And I really don't want to get warning letters because I was like,

I think Joe did that three years ago.

He's on vacation this week. What are we going to do?

You want to have all of that in place and be able to say, oh yeah, Joe's on vacation this week, but here's everything that he knows and lay it out and then again be able to take credit for all that great work that people are doing.

And that really hits that safety and ethical side because by and large, everyone I work with, that's really something that is so ingrained, it's almost not spoken right. It's just kind of almost taken for granted.

So, I like that you call that out and how important that is. And so, yeah, I really think that it depends on a little bit on the culture, depends a little bit on the funding.

But I think as early as possible in the design phases to start. That QMS, at least with those initial phases, is what I would recommend folks to really consider.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I look at a quality management system almost like a design project when you're building it out. And so, I'd like to dig a little deeper in one of the things you had mentioned earlier, which was that road analogy, three lane highway versus a windy mountain road.

Are you able to draw that or can you link that directly to a real-world medical device example to kind of give just maybe some idea of am I a three-lane highway or am I this mountain road?

I don't mean to put you on the spot here, but do any examples come to mind to kind of fill that imaginary gap there?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, this is where I think my analogy may break down a little bit. But I'm going to say, like, if you have a Class 3 device and let's say that it's an implantable device for a medically fragile population, maybe say it's like pediatrics or something.

Obviously, there's going to be a lot more care and a lot more scrutiny for those high-risk Class 3 devices.

So, there's going to need to be a lot of attention paid. There's going to be a lot more documentation in the system because there's going to be a lot more testing and a lot more review.

Clinical trials, probably multiple clinical trials, especially if it's innovative, you're going to have a first inhuman before you go into a pivotal trial. So, in that perspective, because I could make the argument that the winding mountain road is dangerous in its own way compared to the three-lane highway at the highway speeds. Right. So that's where I think my analogy breaks down a little bit.

But let's say a quiet, slow road, maybe not through residential, but just like a quiet back road, maybe through the woods, that might be a little bit safer, right. So that might be more like your Class 2 or your Class 1 type devices where okay, we know that an adhesive bandage is not nearly as high risk as, say, a pediatric implant like we were talking about earlier.

But that doesn't mean that we don't care about the safety or the efficacy of that device, because I know a lot of adhesive bandages. They look at the inks that they use, and they do the biocompatibility testing to make sure that it's safe.

If they're going to put new types of inks and new colors because it's the new design that they're putting out, I might want to see soccer players on my bandage. Somebody else may want to see Disney characters. I don't know. Right. But they still have that same level of care and concern that's appropriate for that level of the device.

So that's where I think the analogy is, that you think about what's that intended use, how does it fit into the regulations, and how's my quality management system going to support that.

So, there's a little bit of nuance with that too, because some of the lower risk devices are what they call GMP exempt. And so, it's not automatically all Class 1 devices are GMP exempt.

You really have to look into your specific product code and where it would fall and what that intended use is and what the FDA has decided.

But even with GMP exempt, like a lot of government terminology, it's a little bit misleading.

It doesn't mean you're exempt from having anything at all. It means you're exempt from 100% of the requirements of Part 820. It means there are some things that you can omit.

However, when you really get into the weeds, some things at first look like you don't have to do them. And then when you come around to the back end, it's like, oh, but I need it for this other requirement over here.

So, did I really get out of a lot? A little bit, yeah.

Etienne Nichols: So is it safe to say if you are a medical device company, Class 1 to Class 3, you do need to define your approach to quality, and maybe this kind of strikes at the heart of what truly is a quality management system versus what we sometimes call a QMS.

And I don't know if you want to speak to that. I don't mean to speak cryptically. We can talk more if you like. What are your thoughts?

Rob MacCuspie: Well,

yeah, this is a good point about nomenclature, because I hear folks use and I'm even guilty of this myself, I'll say like an eQMS, and I'm referring to the electronic system that is supporting the quality management system, and it's also the people and the processes that are going into it, right? And so, there's document management. And I hear people talk about, well, I'm just going to have my document management system. And believe it or not, as recently as five years ago, I was working at a company that used pen and paper and locked filing cabinets and everything had wedding signatures.

And for them, that works good for them.

I like to think about I grew up watching a lot of cartoon shows and reruns as a kid. So, it's like, okay, do I want to live like the Flintstones, or do I want to live like the Jetsons?

I'm aspiring for the Jetsons.

I don't have my flying car yet, but self-driving cars might be around the you know, it's one of those things where there are document management systems and they support the quality management system, and there's the overarching set of processes that go into it as well. So, it's not just, okay, I've got everything accessible. That's a part of it. To me, one of the most important parts of a quality management system is the people.

We were kind of talking about, hey, what do we think the most important part is beforehand? And so, it really inspired me because the people to me are really what makes the quality management system, because you can have a culture of, hey, look, we're all committed to this.

We want to make this right, and we want to get the job done right. And it's almost like I looked at it as like it's a safety net because if I'm working at heights, I might have like a harness and I'm strapped onto something, so I don't fall off the edge, right. I mean, there's a reason I don't work in height construction because I probably would, but I've got my quality management people, the QA and QC folks, they're like my safety. Like if I forgot to sign something or forgot to do something a certain way, they're going to come back and say, like, hey, did you mean to do that or do you need to go back and fix that?

And so, it's like a safety net. It's like a safety harness for me. And so, to me, the people is one of the most important parts, and I think that's often overlooked or taken for granted because we get so focused on what's the actual process we're going to follow, how are we going to do this? We get into the weeds of the design choices and how do we document it? We get into the weeds of how are we going to test it to make sure that it's working the way we wanted it to.

And there's a human element involved in all of that. So, I'm kind of curious, your perspective too, about what you think some of the most important parts of a QMS are.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that's a good question. And yeah, we were kind of throwing this back and forth, but we reserved the answer until we're actually recording. So, get to surprise each other here.

So that's really good. I agree. Without the people, I mean, you don't have anything.

But I would go maybe one step further. So, I'm going to yes, and it's the people, but yes, it's the people. And specifically, in my mind, it's the management. And the reason I say that is management responsibility.

When I look at the overall, just the overall part 820, and the different requirements and responsibilities there, management responsibility is what drives the quality all the way down to the lowest level. And I don't know, it should not be this way. It's kind of like economics.

If you put something on a spreadsheet, you say, okay, this should work. But then in real life, why does it break down? Well, people are incentivized in certain ways, and I don't mean to draw this to money, but let's go back to the management illustration that I would use is if management is committed to one thing and the people are committed to something else, who usually wins in that scenario? Typically, eventually, whatever management is committed to is what plays out in the end because we all are kind of, we're in this together, but at the same time they're driving the ship.

So, I definitely agree with what you said. I think I'm just going to yes and emphasize that management responsibility section, to me that really is if that isn't in line, nothing else is going to matter because nothing else is really going to truly work.

I don't know what are your thoughts.

Rob MacCuspie: I really like that because I don't want to get too much into leadership philosophy, but there is definitely a responsibility of management to set the culture of an organization. And so, yes, in terms of setting priorities and setting goals for the organization and then walking the walk as well as talking the talk, that really helps set the culture for the organization. And so having that flow from the top, yes, absolutely is critical. In addition to, yeah, there's management review board activities that have to take place and as they should, because you want the people at the top who are accountable for this to know what's going on and to have visibility to this and be asking those hard questions of is this the best we can do?

Etienne Nichols: Right. So, this is really good. I have another question though, maybe specifically about software as a medical device. Because a lot of times I don't know, I don't know what your perspective is.

My perspective of the industry recently, in recent years anyway, is we have a lot of software developers coming into the medical device industry and they say, okay, this is cool, you're all medical device people, but we're software.

And then we have a lot of medical device people going into the software industry saying, okay, we have to slow things down and do it this way. And I'm being very over generalistic and it's not probably not 100% true in any one case, but just kind of as an average this seems to be the case.

There's an influx of software developers who are looking around saying why are we going at this pace? Why is there so much documentation needed? And maybe it's rightfully so, but what are the differences?

Are there any differences between a medical device company, just a standalone physical product, and a software is a medical device company when it comes to the quality management system? What are your thoughts?

Rob MacCuspie: So, on one level there's not differences because they're still going to make sure their product is designed safely and effectively. They're still going to test it to make sure that it works.

On another level there is a difference because how you test software is completely different than how you manufacture a physical artifact.

Now obviously companies that have both hardware and software elements to their products are going to have to do both of those. So, if your software as a medical device, yeah, you don't have to fill out details on all of those manufacturing SOPs and subparts of Ink 20, but you do still have to have at least one little SOP in there to address, hey, we don't actually do physical manufacturing, therefore love us, we don't have to do anything.

I'm stealing that phrase from my colleague Michelle. I love that phrase.

There are savings and efficiency gains. I don't want to discount those. And at the same time, there's a lot of documentation that is not up to the 21 CFR part eleven with the traditional software industry.

From what I've found, just having a ticketing system is not always a way that is suitable to document. Here's every change that I made. Here's how I did my design controls, here's how I did these different aspects.

So, it's a helpful tool, but it may not be everything that is needed. And so, there's a lot of, okay, well there was the spirit of these things from the industry I'm coming from, and I need to add a little bit onto that.

So, I think I've seen that tension as well. Kind of like the caricatures of like, let's go at lightning speed versus no, we've got to really slow down. And I think there's a healthy friction there because it reaches a good compromise.

I would also say that there's been a lot of concern expressed by the industry about can the regulations keep up with the pace of innovation in the software field.

I would propose that that's always going to be a challenge because government is by its nature not going to be able to move as fast as innovative startups. So, the folks that are on that leading edge of the wave of the innovation are probably always going to be frustrated in some sense that there's not enough clarity of okay, but there's a cookie cutter approach of what I have to follow. It's like, well, but there's not a cookie cutter approach for something innovative and disruptive either. Right. So, it's part of the price of admission into that world.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. You mentioned something about the government and maybe not being able to move as quickly, and for those of us who wish they would, so that my software or whatever could move faster, I really recommend thinking about that very long and hard.

Do you want the government to move as fast as you do? Because then you're going to be yanked around in different ways. You'll always be dealing with multiple changes. We already are dealing with a lot of changes, but can you only imagine if they moved as fast as maybe a software company?

That'd be tough.

So, one of the things that I think about when I think about those regulations changing is fully understand why it's there.

Regulations in themselves are boring, but the history that led to that regulation is rarely boring. It's usually pretty interesting. What in the world happened to cause someone to ask to add radiological to the CDRH?

There's that whole foot. I wish I had the actual footstore where you were, okay, I'm going off script here, so let's move back. But look that story up. It's very interesting, some of the things that led to these regulations, but I say all that to say fully understand why the regulation is there.

You may actually be meeting it in some way, and maybe you can speak to this if you already do certain amount of verification testing on your software, maybe you're already meeting that IQ, OQ, PQ requirement, or maybe only minor modifications to your change control could meet the requirement.

I don't know if you've seen some of that or have any examples.

Love to hear you expound on that, if possible.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, a lot of great comments there. I'm kind of like which one do I want to jump on first? Yeah, from the regulation perspective there's absolutely I agree with that. You don't want the government to try to anticipate where things are going to go because it can lead to situations.

I saw this with I was in the Nanomaterial space some number of years ago and Europe got very aggressive with regulations, and the US was kind of lagging and so people were going, well, I want to know what the US is going to think.

But I don't want Europe because they're telling me to do things I don't want to do. And so, there's rarely I had a buddy in the Coast Guard, he said, yeah, it's one size fits all, three sizes too small.

A lot of times asking for those regulations, like you pointed out, can be a little bit hazardous. But to that point, when the companies come in with that approach to the safety and the ethical perspective and the commitment to.

Making it effective. There's already documentation in place, and they're already using tools that's like a great platform. And so, it might meet the spirit or even be above and beyond that spirit in some cases, but there's like this little it seems like a little thing compared to the spirit of it, but it can trip everything up downstream. And so, it's one of those things, like, maybe an example might be like, if I didn't use Grammarly and I'm using there incorrectly, it kind of waters down the credibility of everything else that I've done right.

And so, it's a little thing compared to the heavy intellectual lift of the story and the document, but you don't want to lose that. It's the same kind of thing with the culture is there and the story is there.

It's just the grammar is not quite perfect. So having to help edit that, it's a lot easier of a lift, and it's a lot easier of a culture shift because it's kind of like, okay, we were doing it this way, and it's like a subtle tweak versus, like, oh, my gosh, I don't have time for my designers to write down what they're doing because we won't hit our milestones. But if you don't write it down, you don't have the product, so you're still not hitting your milestone.

So maybe we want to rethink this a little bit and then kind, know, talking about, hey, people are already doing a great and I know we talked about this on the de novo podcast and not wanting to be afraid of de novo's.

That's where I go, hey, if you're doing something really innovative, don't be afraid of the De Novo because you can now set the standard for this new product code, this new technology the FDA hasn't seen before that other people may try to copy and make their own version of.

You get to work with the agency and say, here's the special controls. Everybody else in this space needs to follow the testing they need to do. And it's not like, know, lock out barrier to entry for the competition, but you are kind of setting the bar they have to jump over.

So, if folks are interested in that, there's a lot of other thoughts out there on that.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, and I was thinking just as you were speaking, I was trying to think of an example too, and I thought maybe labeling would be a good one for software as a medical device.

I don't know if you want to touch on that, but I know we mentioned QMSR early in the harmonization with ISO 1345. I believe it's part 820 45 in the proposal because the FDA did not feel like ISO was strict enough with labeling.

So, they have a certain section, and I know a software is medical advice. They may think labeling I don't have a physical product. I'm going to put a label on it, but it is still something that applies to you.

And so, this is one of those things you may be meeting, but how you're meeting, it just may be minor tweaks, and you can be not only fulfilling the spirit of the law, but the letter as.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, yeah. Well, labeling is a really interesting one, too, and I really enjoy it because there's a lot of aspects to labeling that FDA considers that are not obvious from that title.

Right. We think of label as like, what's on the carton on the shelf at the local drugstore, and that's where software companies are like, but I don't have a label, I don't have a carton.

But all of the marketing claims on the website and in advertisements are considered labeling. If there's an instruction for use document, that's considered labeling in addition to, obviously what's on the carton.

So, there's a broader impact. Claims that are made in conversations at trade show right. That is labeling because it's part of the marketing materials. So, the FDA does have an interest in jurisdiction over those marketing claims.

So that's where there really is going to be labeling for every device out there, because folks are going to want to communicate how great this is. And there's obviously some boundary conditions of what can be said and what can't base on the testing that backs it up and based on the context that it's presented in and the audience it's being presented to.

So, there's a lot of really interesting nuance in that labeling question.

Etienne Nichols: And for those of you who are wondering how okay, I thought we were talking about quality management system. I actually just had a thought to tie this back because you mentioned people being kind of the foundation of the quality management system by extension, training and fully understanding that quality management system is going to be very important.

It's one of those management responsibilities, making sure everybody has adequate resources, adequate understanding of your approach to quality.

You mentioned that off label use or dissemination of information. One thing you mentioned was social media. I mean, Twitter liking someone talking about your off-label use if they are promoting off label use, and an employee of your company just liking that, giving it the thumbs up, could land you in some hot water.

So really having a cohesive understanding of your approach to the labeling, the dissemination, all this stuff is very interesting and it's very tied into your quality management system as well.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, we think of it as like a Ven diagram. There’re some things that are clearly regulatory, there's some things that are clearly quality, and then there's a lot that overlaps in that Venn diagram.

And labeling is one of those because we helped a lot of clients make their marketing SOPs so that they can train their marketing staff and really all of their staff on, like you said, hey, you can't just go home and like Aunt Betty's post on, hey, this supplement cured my cancer.

It's like, well, okay, maybe it did for you, but as the supplement company, they can't go out there and like that because they're now making a drug claim that hasn't gone through the appropriate clinical trials at that point.

And it's a big risk for the company. I made an extreme example to illustrate the point, but it can get into things that seem less serious but are just as black and white in the eyes of the enforcement agents.

And so, yeah, having that quality management system to say, look, we are documenting people, it derisks that risk for the company, and it helps bring people together in that cohesive culture. They feel more confident in what they can say and what they can't say in the context.

And it gives you that control that, hey, just like you put the thought into the marketing, just like you put the thought into the engineering, and now we're helping scale that for everybody so that they all get the same thing. That's where the quality management system again, the documentation, the processes, the people, all of it rolled into one is really going to work well when all of that comes together.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

And all of these things’ traceability to this, to that. That is very key. That's one of the foundational pillars in my mind of a quality management system. And so, I might ask you the question, how does one start a quality management system or QMS?

So, I just open a Google doc and start typing.

What are the best practices? What are the best companies doing?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, so the best companies, like I alluded to earlier, are going to have a plan when they go into it. So, at Proxima, we help clients develop what we call a QMS roadmap.

You can tell certain analogies that we like.

So, it's the idea of, like we're talking about earlier, what needs to be built when for that company, for where they are in their process and their goals. So, if their software is a medical device company, that's going to look a little bit different, say, than a pure physical device company or versus something that's integrated.

So how do I go about starting it? You make the plan. You identify how I'm going to do document control as a company, what people are going to need to be involved. I got a responsibility matrix who's going to cover what bases, if you will, and make that plan. Now I can kind of sit down and say, okay, now I open my Google Doc and start typing and work on the draft of my colleagues.

And now we're going to route it through our document control system once we're finalized and sign off on it. Do the trainings, get that going. Oh yeah, we got to do training.

SOPs and records. Okay, let's do that.

All of the things right.

But hey, you know what, we can push some of these things off till we hit another milestone. And so that really helps people sit down with the how of how to go and build it out.

Just like you talked about with an engineering design process, right. We have to kind of have a little bit of the end in sight and we have to know what are the steps we're going to take along the way.

And there'll be a little bit of learning along the way. And that's why quality management systems and document control allow for revisions in the process.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, and just kind of to torture that metaphor a little bit.

The design controls process, when you think about it, starts with user needs, part 820 30. Anyway, you start with those user needs go to design inputs and so forth. So, when I say I look at a QMS as kind of a design project, what does your company need?

So, you look at these different perspectives. Who's going to be interacting with my quality management system? Obviously, the employees are probably number one, your company. That's who it's really for.

But most of the time we make number one, the notified body or the inspector who's going to come in and look at it. Now that's obviously important, but they are not the ones who are using those every single day.

Those plainly written. SOPs those should be designed for employee, the employees in mind, at least.

Correct me where you think maybe should change, but then those coming in and auditing you, what are your thoughts?

Rob MacCuspie: I kind of have a really high Aspirational goal. Yeah.

If my SOPs and training process can bring in somebody that has no experience and they can hit the ground running, I'm not worried if the auditor has any experience now in my space, right. Because I now have everything in place to show somebody how they can teach themselves and learn and get up to speed and walk through the process.

Now, obviously it's not going to capture 100% of everything, but if I'm writing things in a clear manner, then, okay, maybe if it's somebody in a chemistry lab, they have to have certain basic level of chemistry understanding it's written for that. But if I'm not requiring folks to have a chemistry degree that are going to go work in the chemistry lab, then my SOPs better teach them enough of that chemistry that they need to know.

And so, if I've got trained people, they can explain that to the auditors. Auditors that are examining a company that has chemistry elements have probably seen that before. They may not be experts in that particular type of chemistry.

They're probably not because they see so many things, but they can pick it up pretty quickly if you've got all of that training in there for someone that has a reasonable level of experience.

So, I feel like it’s kind of can hit both of those goals if it's really well written and yeah, the people that use it every day are your team, are the people that are working at the company, or in some cases people have contract design firms or contract manufacturers.

And depending on the level of oversight that you want or need, you want to make sure that they can come in and do what you're asking them to do.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that makes sense. So, we've kind of talked a little bit about the SOPs the specifics of them. There’re two different things. When I think of document control, I think of document control, maybe part 82040, I believe it is document control, where it talks about what kind of defines document control.

But when we look at medical device companies, there's usually a document control department. There's document Control, the technology we use to control our documents, whether it's a filing cabinet or a password protected server of some sort.

Can we talk about a little bit about the technological side, whether it's paper versus electronic? And what are your thoughts there?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, the paper side is fairly intuitive, I think, for most people. And everyone's aware of the cumbersome nature of it, especially with remote and distributed workforces. This day and age mailing documents back and forth.

I don't know, maybe carrier pigeons might be faster, but it's not efficient for the way we do business today. So having electronic options is great.

There can be kind of these hybrid things where maybe I've got Part Eleven compliant esignatures, and then we all esign a PDF for our routing and then we have a secure way to store that on servers that are password protected, and the read write access is controlled so that it's always the current versions.

And that's kind of like a digital equivalent of the binder on the manufacturing floor with the paper. SOPs so there's kind of that middle ground. But then what's usually most easy for people to work with is an integrated system that handles the digital signatures that handles the document control.

Serves you the most current version when you're looking for it. So, you don't have to worry about is that paper copy outdated or is that file outdated? It hasn't been updated in two years.

I can't believe it as innovative as we are. Right, well, maybe it has just no need to change, right.

So, you're able to have more confidence in that.

And so, yeah, there's a need for document control, especially as companies grow, because the number of documents is going to increase. And so being able to manage that efficiently really adds value to the organization.

And so, then the tools that support those folks are just as important. A question we get asked a lot is, well, but hey, my Google Docs tracks who made what edits to this document, why do I need anything else? And the short answer is it's not compliant with Part 11. The longer answer is to make it compliant with Part 11, you probably have to do so much work that you would rather pay to have a solution off the shelf.

Etienne Nichols: Right.

Rob MacCuspie: Most people I have found prefer to do that approach, not to say it can't be done.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I mean, if I ran through, I used to just kind of mention a little bit about part 820 40 when I talk about document control, the requirements. I mean, it's very simple when you really look at it's only a couple of paragraphs long, go read it.

I definitely recommend people to do that. But essentially, you're saying, why did Rev A go to Rev B?

Who said this was, okay? Who approved this change, and on what date did they change it? So, when you say, okay, well, Google Doc, they track all my changes, it doesn't really say why you did that, doesn't justify those changes and give a departmental approval or just the impacted areas approval.

So, there's a couple of things lacking there. And like you said, that's interesting. I've never really thought about how would I make that Part Eleven compliance? It would be a big job.

So that being said, I don't know. What are some of the best companies doing? Well, actually, let me back up a little bit. Sorry, I was about to go down another Ted Talk, and I don't want to do that.

What about the bigger companies who they're set in their ways? Maybe they so we could look at companies who have just maybe I want to get something off the ground, I've got a new product and so forth.

But we look at a bigger company because I've actually worked at Fortune 500 companies that are still working on paper. Maybe their actual SOPs are Bloated because they're trying to cover both biologic and medical devices.

How do I trim those down? What about the other spectrum? Because we do work with a lot of larger companies, and how do we help them get to the best place?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, so that's a great question because making a QMS efficient for the organization is a big challenge and a continuing challenge. I like to think of a structure for how I'm going to design things kind of in almost like a pyramid.

So, I've got SOPs that are kind of overarching to the whole organization.

And then I might have SOPs that are specific to, say, certain pieces of manufacturing equipment or certain tools, certain analytical equipment in the laboratory for QC release. And so, I've got kind of, okay, this is how to use those tools.

And then I've got a process, and then I don't have to update every SOP that uses my calipers when I want to make a measurement because I've got that one. SOP over here I can reference hey, use caliper measurements and reference the SOP, and then I can have the process of like, okay, now I'm thinking about that process.

I want to mix these two things together, put them in a mold, compress them whatever, and then I'm going to make my measurement that's the right size and I'm good to go to the next step.

So, there's ways to think about how to focus the scope of those SOPs and not try to make it be so all encompassing at that broad level that, okay, I'm trying to do for devices something that only applies to biologics, but I didn't quite think about the SOP and the scope and applicability.

Quite right. And so now I'm cascading that down. And so that kind of can create some Bloat, right? It can create, well, I've got to do all of these things for everything when maybe I don't have to do that for everything.

Everything. Maybe just some things. Maybe it's 50% some things.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

That makes a lot of sense from the content side of your quality management system. We talked about the other side, the document management side or the document control, I don't know which.

However, you want to look at this, the actual tool you're using, whether it's Paper or a server on your own physical drive or however you want to handle the electronic side, how do companies, instead of taking that leap, maybe a big company that it's going to take a while to change their tools.

They recognize we're in a sad situation from a technological perspective. We're still using Paper. We're still using Google Docs and Dropbox and DocuSign. How do they instead of taking the leap and just trying to make a quick switch, how do you get that boat up next to the dock?

Is there a phased approach where you can say, okay, for this limited amount of time, we're going to use this existing system, but we are also moving over here? How does that work?

Any thoughts?

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, there are ways to explore some creative solutions like that. For sure.

You can look at some creative ideas to try to set some boundary conditions and some scopes and say, all right, we're going to say at the highest level, we now have the flexibility to choose A or B during our transition period, right?

Maybe we intend to transition. And so now we're going to focus on we're transitioning maybe this business unit or some compartment that makes sense for the organization and move that part over and kind of get comfortable and familiar with it and then roll it out in a more broad context.

Again, maybe in a staged approach like we were talking about earlier, because resources are always limited, right.

There may be some creative ways to look at opportunities to do that.

Obviously, it's one of those things, though. The longer that a hard task is put off, it's going to continue to rack up debt. Right? So, I always look at it as like, okay, how long do I put off my QMS if I'm a startup? Well, every day I don't do today's work now.

Tomorrow, I got to do two days and then next week. I got to do five days, well, six, really, because I got to do Monday's work too, and all of last week's.

And then it just continues to pile up in the same way. It's like, well, we can't afford to do this.

Can we afford not to do this?

Is the other question. And that's a question that, again, has to be answered by management. There's a lot of considerations in there, and one of the concerns I've heard is, what if we make mistakes in the switchover process? How do we ensure that? And again, there's ways to address those concerns and make sure that there's the right checks and balances in place without it being burdensome to migrate it over.

And depending on how much effort people can put into it, it can be a great time to look for some of those content efficiencies in addition to just the document control efficiencies that can be gained.

Etienne Nichols: I definitely agree that Parkinson's Law is in full effect. When you're trying to make a big change like this, the amount of work does expand to fill the amount of time you give the maybe not taking a leap, but like you said, a staged approach makes sense to me.

That being said, what about some of the returns on investment from a regulatory standpoint? So, the argument might be made that, okay, we are where we are. Well, we've been here a while.

It is kind of what it is. Do regulatory agencies look more favorably on a more advanced quality management system?

Or why would they if that were the case? Maybe they don't, but what are your.

Rob MacCuspie: Thoughts from a pre-market submission perspective? There's not a lot of concern on that front as long as it's meeting the requirements.

It kind of goes back to that conversation we're having a little bit earlier in the podcast about they're not going to dictate to you that you have to do it a certain way.

They're going to say, here's the requirements. You figure out how you're going to go meet them. Now, that said, you could have an amazing car. Pick your favorite sports car.

Maybe it's a Ferrari or a Maserati or whatever your favorite is. You could be an extremely safe driver with that car, or you could be an extremely reckless driver with that car.

Yeah, they're kind of looking at how are you driving?

As much as, okay, well, is the car safe to be on the road? It could be the 2003 car that I learned to drive on, if it's still road safe.

Etienne Nichols: The thing that it makes me think of as you talk in there, I was kind of thinking back in my experience with FDA inspections in a paper-based system versus something else, and I can remember, okay, the back room.

We always talk about the war room. The war room where they're up front, they're talking to the inspectors. There's maybe two or three people there in the back room with paper because they are going to those filing cabinets, those vaults, maybe requesting things from Iron Mountain, which is a legitimate thing.

When you ship those off after a few years, that may be ten or twelve people in that back room, depending on the size of your company, and thinking about how much time they're spending not doing something else, that's a pretty big deal.

That's a pretty big resource lift or drain. And so, one of the things that I think because I think you're right, who cares?

The FDA probably doesn't care what kind of quality management system you have. They care about the results. They care about how you're driving it. Are you able to get me this document in time?

Are you able to get me the right document? Is it traceable to other things? That's where the rubber hits the road in my mind again, to torture the metaphor of driving.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah. So, we're going to drive it into the ground. Sorry for let's do it.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I've got more time, too. I don't want to take up all your time, but this has been fun. Keep going.

Rob MacCuspie: Yeah, I've got a few more minutes, but yeah, it's one of those things where audit preparation you described a really good audit preparation process. You've got the people that are interacting with the auditors and asking for exactly what it is that they're looking for and trying to understand both what they're asking and maybe what they're looking for isn't what they're asking directly for yet.

Right. Because sometimes they'll pull on the thread to unravel the whole sweater.

And so, understanding okay, like you say with that traceability, yes, we've got this. And then they're going to ask for this and this. So, let's get the folks ready.

If you've got a large company and lots and lots of products, I've heard of some companies having over 100 audits a year between ISO and FDA and other agencies. So now you're talking about, again, whole teams that are basically just dedicated to doing nothing but audits.

What else could that team be freed up to do to contribute to the quality of the organization if they could do that job more efficiently?

That's a great question and one that I think those large organizations probably should look carefully at.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that's a great point.

I don't want to take up all your time. I really appreciate you coming on the show today. I do want to give you a chance, though. Do you have any closing statements and where can people find you?

Rob MacCuspie: Sure.

I guess my closing thought is that I love that quote attributed to Peter Drucker, that culture eats strategy for breakfast. And all the variations of, you know, having that culture from the top, like we were talking about.

I like your analogy there of focusing on the people, focusing on the mission, focusing on we want this to be safe and effective we want everybody to live better, healthier lives.

That's why we're doing this and bringing that all together, that really encompasses the quality system. It meets the regulations that are required, and it really creates a strong organization, and it builds the reputation of the brand, and it helps people feel good about what they're doing.

So, there's a lot of opportunities for quality management systems to be more than just a filing cabinet.

So, there's my Ted Talk for what it can be.

Yeah, you can email me. It's robmccusby@proximacro.com. I'm on LinkedIn. Feel free to reach out to me there. You can find me on the Proxima website. We'll put some links in the show notes, I guess, and yeah, look forward to talking to anyone that wants to learn more about this.

Etienne Nichols: Rock on. We'll definitely put those links in the show notes, so those of you who've been listening, go check those out. He has a name. His last name is a little like mine.

There’re probably multiple ways to spell it, so we'll put those links to make it a little bit easier for everybody. Rob, thank you so much for being on the show.

Everybody. You've been listening to the global medical device podcast. We look forward to next time. We'll all see you all later.

Thank you so much for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, reach out and let us know, either on LinkedIn or I'd personally love to hear from you via email.

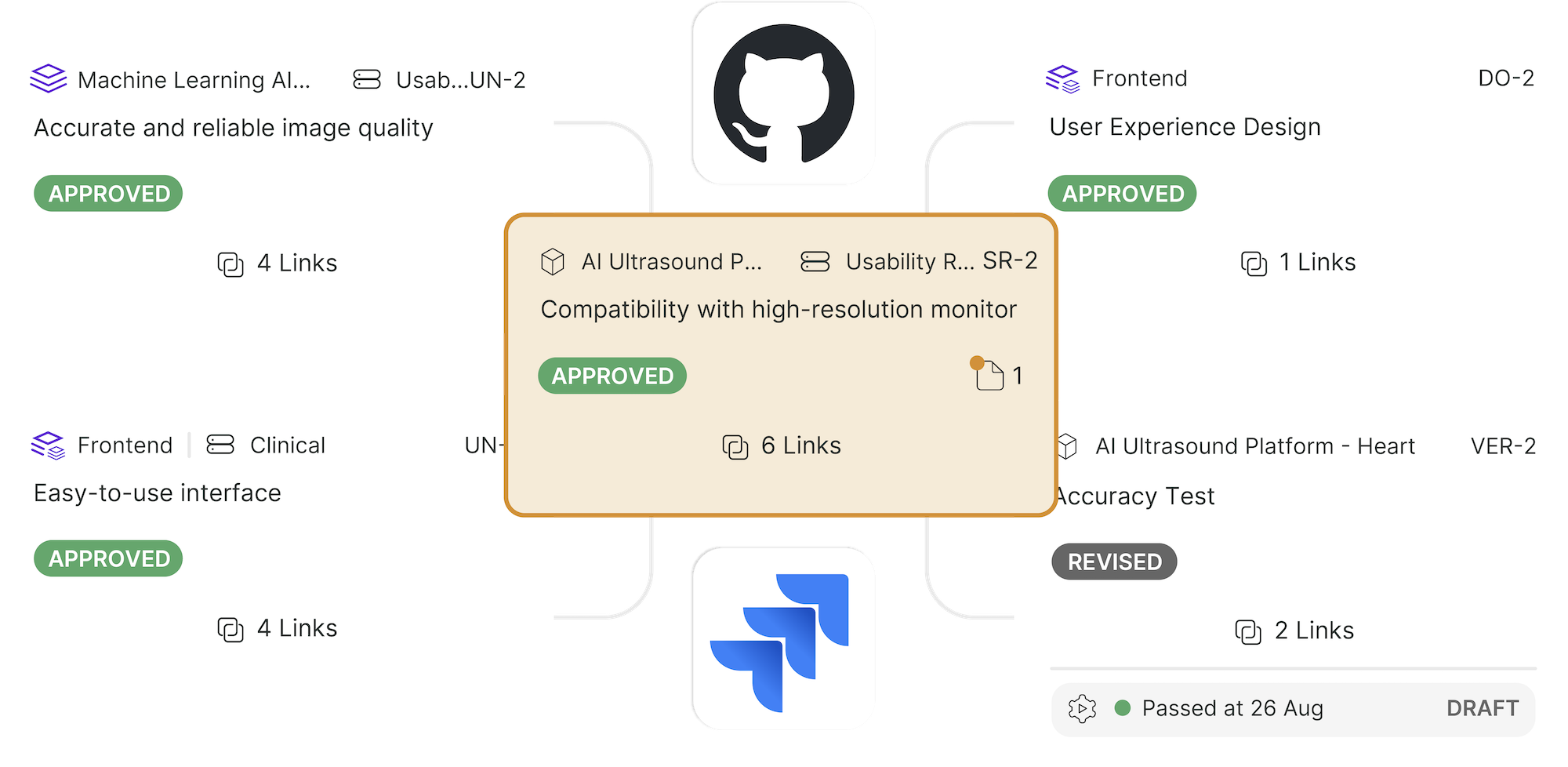

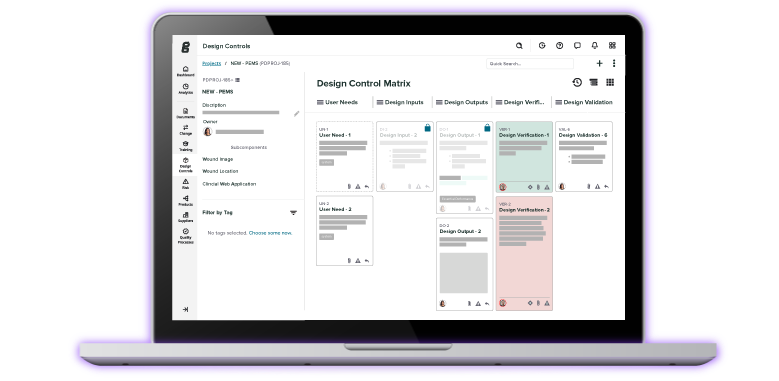

Check us out if you're interested in learning about our software built for MedTech. Whether it's our document management system, our Kappa management system, the design controls risk management system, or our electronic data capture for clinical investigations, this is software built by MedTech professionals for MedTech professionals. You can check it out at www.Greenlight.Guru or check the show notes for a link. Thanks so much for stopping in. Lastly, please consider leaving us a review on iTunes. It helps others find us. It lets us know how we're doing. We appreciate any comments that you may have. Thank you so much.

Take care.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

.png)

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...