What are guerilla tactics for quality leadership? How do you implement a lean quality management system (QMS) and put requirements in place that are truly required - especially when there is the potential for personnel to resist change?

In this episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne Nichols discusses lean QMS implementation with Steve Gompertz, a leader in quality systems management with more than 30 years of experience in the medical device/technology industry.

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some highlights of this episode include:

-

Guerilla tactics for quality leadership that involve thinking outside of the box and trying to get things done without asking for permission from authorities. Sometimes the FDA unintentionally creates fear and creates imaginary boundaries in people’s minds that stifle their creativity.

-

People will struggle and become frustrated when working with a burdened QMS and restrictive standard operating procedures (SOPs).

-

The regulations and standards are intentionally vague and open to interpretation because it’s not possible to have a one-size-fits-all. Meet the intent of the requirements and be ready to defend them.

-

Lean documentation is the best approach. Weed out the things you don’t need. In a regulated or unregulated space, it’s better to have clear, precise, and intentional documentation rather than a pile of papers.

-

Sometimes regulations and standards create negative opinions because it’s human nature to not want to be told what to do. However, what is their purpose? To produce safe and effective medical devices while also turning a profit.

-

Approaches to implementing guerilla tactics include burying or sneaking something in without calling it what it is and getting people to do the right thing without them always knowing they are doing it.

-

Make sure your metrics don’t incentivize the wrong thing. Some companies measure document control in QMS based on time—how fast it takes to make changes? But does that actually make the process more effective and cost less? More likely, it incentivizes cutting corners.

-

Steve recommends shifting your mindset about document control or value-added changes by first defining the problem correctly. Don’t make assumptions.

Links:

Quality & Regulatory Consulting - QRx Partners

Ask Me Anything Session with Steve Gompertz

FDA - Guidance Documents (Medical Devices)

21 CFR Part 820 - Quality System Regulation

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

Greenlight Guru YouTube Channel

MedTech True Quality Stories Podcast

Memorable quotes from Steve Gompertz:

“The regs and the standards aren’t actually that specific too often. They are intentionally vague. Sometimes, that is a point of frustration with people. But when you think about it, they have to be.”

“Step back, stop just reading what the words say, and start thinking about why are they there?”

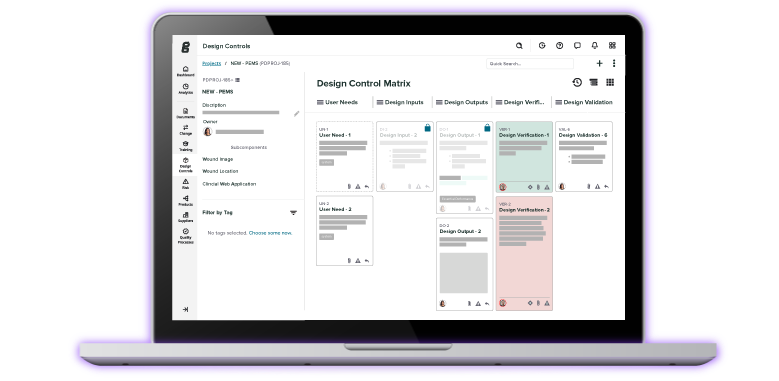

“When you create a quality system, you have to think about the architecture.”

“If it isn’t documented, right, it didn’t happen. If it’s not documented right, things are going to go bad.”

Transcript

Announcer: Welcome to the Global Medical Device Podcast, where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols: Hey everyone, welcome back. This is Etienne, your host of the Global Medical Device Podcast. Today, I'm going to be talking with Steve Gompertz. I hope I didn't mess up his name again. I think I messed it up when we talked in person. But he is a leader in Quality Systems Management with over 30 years of experience in the medical device and medical technology industry. He and I talked about Guerrilla tactics for quality leadership and really implementing a lean QMS, putting the requirements in place that are truly required. His career includes roles in quality system development and project management, engineering automation, configuration management, audit software development. He runs the gamut. He has worked for multiple big companies that you... Well, we'll just go on from that. But Steve, he holds a bachelor of science in mechanical engineering from Lehigh University. He actually teaches a masters course at St. Cloud State University. He really has some interesting thoughts when it comes to quality management system, building those documents out and I really enjoyed this episode. Also, I will say one other thing. We are actually holding and ask- me- anything session with Steve on July 20th. If you're listening to this before July 20th, 2022, you are welcome to come into our community, the MedTech Excellence Community that Greenlight Guru has built out. We're going to have an ask- me- anything session with Steve. If you want to go to that, it's community. greenlight. guru and you will need the access code, or at least as of right now, you'll need the access code, True Quality 2022. I'll put the link in the show notes and hope to see you there. I hope you enjoy this episode as much as I did. Thanks. Hey everyone. Welcome back to the Global Medical Device podcast. This is Etienne Nichols, your host of the podcast. Today with me is Steve Gompertz. Am I saying your last name right? I should have-

Steve Gompertz: I like the way you say it. I just say, Gompertz.

Etienne Nichols: Gompertz. Okay. I'm getting too fancy over here. Well, everybody's heard me say this.

Steve Gompertz: A little too European, but that's probably how they'd say it.

Etienne Nichols: I'm excited to be with you, Steve. I'm especially excited about our topic today because and I think our audience will really respond well to this because it's about quality management systems, specifically the guerilla tactics for quality leadership. When you sent that title over, I was excited reading about that, but tell me what that means to you. What do you mean by Guerilla tactics for quality leadership?

Steve Gompertz: Yeah, it's obviously meant to be eye- catching. It's kind of to create a reaction, but it's really just about thinking outside the box in colloquial terms. The best way to describe it is just how to get things done without asking for permission and not getting fired. The title definitely always catches everybody's attention. I borrowed it actually from another consultant decades ago where I went to a similar session that he was giving, what was at the time called Concurrent Engineering. We now think of that as integrated product development. But back then, that was the hot new term. I was at a conference and he was doing this talk on Guerilla tactics for Concurrent Engineering. One, I liked kind of the boldness of the title and he had lots of really great ideas for just not just how to get concurrent engineering in place, which how to implement change without the authority to do so. A lot of people, I think, struggle with that. That's really what... When I do this workshop, that's what it's about, is how to get your past those barriers.

Etienne Nichols: That's a really good something you bring up there when you said doing it without... Maybe having permission without getting fired or any negative repercussions, hopefully it doesn't get to that extreme. But I think a lot of people maybe if they've not been in the medical device industry or maybe if they have been in the medical device industry and have worked for large organizations with very burdened quality management systems or restrictive standard operating procedures, that is a struggle. A lot of people probably feel like these regulations are too restrictive. What's your response to that? How do you react when people talk about those types of things?

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. There's a couple of things going on, what you just asked there. I get the element of on a regulated industry, it seems tougher to kind of go outside the boundaries. The topic though, really does apply across just about any industry or not just quality or any function. But to your point, you're right. That big hammer everybody's head of the FDA or whatever regulatory body it is always creates this fear." We can't do this, we can't do that. FDA will hate it. An auditor will find this and write us up for it." Early in my career in the med device industry, that's what I heard a lot of. That was sort of the anecdotal training was don't do that because FDA. That was the much tones, will not like it or not approve it. And then as I became more of an actual student of the regulations and the standards, really started to become a professional rather than a hobbyist around this stuff, I sort of realized the regs and the standards aren't actually that specific too often. They are intentionally vague. Sometimes that is a point of frustration for people. But when you think about it, they have to be because there's no way to just have a one- size- fits- all. To me, I kind of flip that around and go well, then I'm pretty open to how I want to interpret this as long as I can defend it and show that yes, I'm meeting the intent of these requirements. The requirements are broad. FDA inspectors and other types of auditors will tell you that. Yeah, we don't tell you exactly how to do it. Tell us what you believe is right for your environment, your organization and be prepared to defend that. If you convince us, then we're good. But they're not coming in with a pre- prescribed notion of exactly what your quality system has to look like or what that particular activity has to look like. Except like I said, in a few rares instances, like if you look at 820, complaint management is one very specific to the information they want. Why it's so surprising that so many companies get written up for that, but that's a whole nother topic.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. That's maybe one we should cover at some point. That's a good one.

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. That is a good one to talk about. That and Kappa, two places, they are really pretty specific and everybody gets it wrong. I don't understand.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. We'll have to figure that one out sometime. All right. Well, I am curious though. A lot of companies have these very massive documents. Maybe like 30, 40, 50 page quality manual. What do you advise companies? Have you had experience in that sort of thing, trimming those down, making them still... What are your thoughts there?

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. That's a pet peeve of mine. When I do the workshop, there's a whole section basically on lean documentation as a better approach. I think again, that idea that in a regulated space, we better say more to be really clear and one for the auditors. Again, I don't know why we always write for the auditors. They're not working with us every day. They come in once a year, maybe. But more importantly, to the people that have to then perform activities under these procedures or work instructions and we feel like we've got to be really prescriptive and detailed and these things just become massive and it works against you because nobody wants to read that, especially if it's words. I push the ideas of move more towards the lack of words, images, how about videos? Let's rethink what a document means. But if you do have to have some words somewhere on the page, it's just, how do you just lean it out to what you actually need? Again, it comes back to, do you understand the intent of whatever requirement you're trying to meet within the standard of the regulation? Quality manuals are usually... It's the starting point. When you have that typical pyramid of what everybody's quality looks like, the triangle at the top is the quality manual. If you think about that diagram, it's the smallest object on the pyramid. Why is it the largest document? I took over position as head of worldwide quality for a company and a week later, we had an audit come in. I don't really know anything about how the company operates, but I sit down with the auditor and typical they ask for," Hey, could I see the quality, Daniel?" And I slide a 45 page document across the table to him. He picks it up, kind of like that old thing about a professor weighing your paper to decide what your grade is. He's just sort of holding it, feeling its heft. And then he looks at me and goes," Tell me again, how many requirements is this designed to meet?" And I said," Three." And he goes," But it took this much paper to describe how you satisfy those three requirements?" My answer was," I've only been here a week. I'm going to be working on that." My response to that is why do you need 45 pages to meet three requirements? Then I also teach St. Cloud State University, a class on quality systems and several other classes. I always challenge my students going," Well, how small is too small? If I'm telling you to lean it out, is there a lower limit?" They think about their own companies, what they've seen and they can't go," Well, it'd be nicer if it was under 20 pages. Maybe we could do 10." And I go,"Can you get down to single digits?" And then they start getting uncomfortable. Like," I don't know, a small quality manual." And then I always throw out," What if you could fit it on two sides of a piece of paper?" And they kind of go," Well, no. That wouldn't work." And then I whip this out and this is my... Oops, sorry. I don't know if that'll come up. No, there it's. This is my tri- fold brochure version of a quality manual that meets all three requirements and is fully audit- tested both in a regulated and a non- regulated environments. It's met audits in 9001, 1345. So the first time I showed that to an FDA inspector, typical audit," Let me see your quality manual." And I handed him this and instead of weighing it, he looked at it and went," Finally."

Etienne Nichols: That's awesome.

Steve Gompertz: Because there's just certain things he wanted to look for in a quality manually and he didn't want to go through 45 payments to get there. This caused us some shock. The first time I did this, it was in a non- regulated industry for 9001 based quality system. And then I tried to move it into my next gig with a medical device company. And they went," Well, I'm sure a 9001 auditor would be fine with that. No, but an FDA inspector, they're not going to accept this."" Why? The concepts are the same."

Etienne Nichols: So time out for just a second. I've got to ask, how did you feel the first time you took that into an audit? Did you have any trepidation at all?

Steve Gompertz: I didn't. I was pretty confident. Sometimes I'm over confident maybe. And it wasn't like I could blame it on you. Earlier in my career, I wouldn't have hesitated at all. But I just felt like I was at a point in my career where I was on top of my game and the traditional style of quality manuals and other quality documentation no longer made any sense to me. And having been through enough audits and knowing what the expectations are, and again, I don't always base what my decisions and what I think the auditor wants to see. I look at what does the company need to meet the intent, which is we're supposed to produce safe and effective devices. If you're 9001, you're supposed to produce customer satisfaction. What does it take to do that? That's really what the auditors are trying to confirm. Yeah, I felt pretty confident going in. But yeah, it was a good first test. How is that going to fly? And like I said, when that auditor went," Finally, there we go." That's all I needed to hear.

Etienne Nichols: I interrupted you and I apologize for that. So if we go back to your story though, now you're taking into a medical device, two things. I'm curious about, number one, obviously, how did it go? But number two, how did you get buy- off on that company to actually... Maybe that goes back to your Guerilla tactics.

Steve Gompertz: Yeah, that's one of the things I do talk about when I do the workshop is one of the barriers is often... As I said, you feel like you need permission to do this. What if you can't. You feel like you've got a good position to do that. In this case, it was just good timing. There had been other places I wanted to do it and I wasn't going to be able to get anybody above me to allow that risk. In this case, I'd had the idea for quite a while, but now I'm finally with a company that's smaller. And I was part of the actual executive team. The CEO was pretty good at trusting me. That was why he hired me. He understood the logic and he was like," If you are confident that this is going to jeopardize our certification, then I'm behind it." So I lucked out in that case. But if he hadn't, if I had to do it over again and I wasn't going to get total buy- in, what I might have done is had this in my back pocket, gone with an improved revised version of the 45 page or maybe down to 15 or 20 pages just to lean it out as much as possible. But I probably would've offered this up for opinion to the auditor." As long as I have you here, if instead I had handed you this, what would your reaction have been?" Get that other data point that I can then go back to somebody and go," Hey, the auditor said he would've been fine with that and actually saw some benefits." So it's part of building that groundswell. I talk about this in the Guerilla tactics. When you're thinking like a Guerilla leader, you have to sway the masses. You typically don't get to... You have to recruit. You don't get conscripted forces to work with you. You have to convince people and so part of it is building up that rapport and showing them that there is a chance of success and that the risks are not as horrible as they might be. There's always some, but that's part of the Guerilla tactics is you've got to think like that is, how am I going to bring together a uniformal army to go with me on this journey? And the influence, some of the powers that be, maybe become rebels on their own that can include a path.

Etienne Nichols: That's the quality manual. I'm sure there are other aspects or other areas of organizations that you see opportunity to lean out. What are some other pitfalls you see companies getting into as far as that goes?

Steve Gompertz: Well, yeah. I started to talk about just documents in general get to be too big. You go in there just about any company, you do an audit or do some consulting and everybody's SOPs tend to look the same. You could pretty much guess what the first sections are going to be. You're going to have purpose. You're going to have scope. You're going to have applicable documents. You're going to have definitions and roles and responsibilities. We're down five sections, but we've not yet said what to do and that's another thing I pushed back on. And I got this from one of my managers who... That's what he brought up. I was revising a procedure and he said," Why does it take six pages to get to the part I want to read which is telling me how to do my job?" I get it, this other stuff's important, but why does it come first? That's an interesting approach. I've since completely revised my template that I recommend. Purpose and scope are important. Purpose tells you, am I reading the right document and does this apply to me? Great. After that, section three is the procedure. Definitions, applicable documents, reference documents, roles and responsibilities. All of that can go in an appendix at the back. If the reader wants it, they know where to find it. But typically what they want to see is show me the flow chart and flow charts are another big thing that I do. More graphics than words. They typically want to see, what does this look like? Is there somewhere that I can jump to for some additional information and all that background information is that somewhere else that I can find as well? But instead of flooding it to the front and now I get a page and page to page till I get what they want and I'm already losing my audience and becoming bored with this, it definitely flips it upside down and goes," Why are you doing it?"" Well, it's because they said that's what they have to look like."

Etienne Nichols: So really you're building the SOP for the people who are going to be using it, not so much for the auditors.

Steve Gompertz: Right. I think that's the other problem is that these are typically written for the audit or in order to pass an audit, but that's not their purpose. It's one of those theoretical statements I make to my students. And I go," Stop worrying about the FDA." A shock. The look like that. Wasn't what the whole degree program was about, is learning how to not get in trouble. I said," But the FDA wants the same thing that the company needs and that's to operate correctly." The goal of the safe and effective device, that's what we're in business for as medical device. That's what FDA is about as well is just... But we're going to give you some guardrails, some guidelines to follow. Well, they're not guidelines. I'm going to tell you have to do them this way. But ultimately, that's the same thing we want and you do it as a business because it's going to make you a successful business. FDA wants you to do it so you don't hurt anybody. Those two things are not mutually exclusive. I think you just need to get into that mindset of," We're not in the business to pass audits. We're in the business to produce a safe and effective medical device and to make money." That's the part FDA doesn't care about. But there's a way to do that. I always tell people," Stop..." The typical human thing, we don't like to be told what to do. So regulations and standards are just obvious examples of that and we automatically have a negative opinion of them. And I always tell people," Step back. Stop just reading what the words say and start thinking about why are they there? Why did they feel the need to put that requirement there?" Understand the purpose of it and it's intent. And eventually you start to go, even if I wasn't in a regulated industry, isn't this how I'd want to run a company anyway so that it would operate efficiently? Of course, I want doc control. Of course, I want to revision things around. I don't want to lose sight of that. By the way, my intellectual property is probably dependent upon it. So there's all these business reasons for all these requirements, that we are in the regulations and the standards, focus on that. If that drives you and you're going," Well, what's the way in which I should do it?" Now you can refer back to the regulation standard because it'll tell you," Well, here's where the guardrails are. You have to stay on this road if you're going to do this." It just takes a change in that mindset of going," What's right for the business and what are we trying to get? We understand the risk. Oh yeah. And we're going to get our auditor to inspect it at some point. There is this FDA thing. So yeah, we will have to pay attention to that, but don't make that."

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. That makes sense. You had mentioned something about graphics and flow charts. I can look back at my past where we had... Maybe we were talking about design controls and we had a flow chart that was... We went the other direction with flow charts. How do you maintain that middle ground? One other thing and that is, I hear some people say," Well, you don't want flow charts because they're an audit trap because people update the words and they don't update the flow chart." How does that work with the redundancy or what are your thoughts? I'd like to hear more about that.

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. There's a lot to that. When you create a quality system, you have to think about the architecture at first. That's why you have that pyramid as the starting point. But it's very hierarchical or at least it's supposed to be. Which could be a segue back to why are some quality manuals are so big. For small entities, you can just have a single document that is everything. But if you're in a larger organization, you are supposed to think about the architecture, the hierarchy of these documents and that's what the pyramid is supposed to showing, that there are these layers. You have to be very clear about what kind of content exists in each layer, the quality manual is just satisfying three things and just sort of sets the stage. This is what our architecture looks like, this is our quality policy, this is how we interpret these things, here's the roadmap to the rest of it. Then the layer that's often missing in the pyramid is a process layer. Usually, we jump from quality manual to procedures and then you end up with a whole bunch, dozens and dozens of procedures and you go," How are they connected?" And you go," Oh!" Because there is that piece about that it's supposed to be a process based system in the regs and the standards. That's the layer that's missing that you should define the high level. I always use design controls as an example of that. That at that process layer, there should be a document that says," This is what our overall design and development process looks like. We have a five stage process. We do concept development, we do design, then we do development, then we do market release and then post market follow up." Something like that. That's a very simple flow chart to start people thinking," Here's what this looks like overall." Now, that concept stage, phase one, let's write a procedure for how to perform that. Each stage now gets its own procedure at the next level. Within the procedures, you think about,"All right, what are the activities that need to be performed to come up with a good concept to move forward with?" In all of this, you're very focused on what's happening. You're not yet into a lot of detail about how and that keeps some of the complexity out of it. It lets you keep those flow charts a little cleaner, because like I said, you've gone from big blocks, a five block flow chart that says this is design and development. So at least we get the context. Now, we go into phase one and you get another little bit more detailed flow chart that says," Well, these are the activities we have to do." Requirements definition. And you have to do requirements assessment and whatever. Maybe now, there's eight or 10 activity blocks in there. All of you said is that this is an activity that occurs and this is its purpose, but we've still not said how. Now, you make the decision for each of those activities, do you need a work instruction that says step by step," We want it to look like this." But also keep in mind, not everything needs that. Some things it is sufficient to just go," This activity has to occur. It needs to produce these deliverables when it's done." That's all you need. We don't need to tell you exactly how maybe you make it easier but we'll give you a template for that deliverable because we prefer some continuity or not have you waste time trying to figure it out. But you make that more guidance. You don't have to use that template. If it doesn't fit the project you're working on and you have a better idea that works better for your project, go for it as long as it meets these requirements. It's of thinking through the levels of detail and keeping the most detail down to the bottom and don't write a work instructions for everything, unless you actually need to constrain those steps.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. Wow. Okay. That makes sense. The process layer. I do come from a background where the different medical device companies that I've worked for, that was how it was a massive quality manual with those dozens of SOPs that... Yeah, you had to go back to the quality manual to figure out where they went to each other. But that makes sense what you're saying. You're blowing my mind a little bit. Honestly, it is a bit of a mindset shift.

Steve Gompertz: I've been to some places where rather than having a process layer, that process diagram is in the quality manual which then might make the quality manual bigger. But there's sort of combining two layers. As long as you get the concept of what is more typical, is you go from this very high level stuff in the quality manual, which typically is also just a repeat of what's in the standard, which is not valuable at all. And then it jumped down, like I said, you have this big pile of procedures that are not connected. And then they wonder why things are inefficient and they have non- conformance because nobody can see the bigger picture because you didn't draw it in the right way.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. As you go through and work with companies, I guess just the way you just did with me talking through it, showing how it works, that makes sense to me. If it's audit ready, then why would you argue against that? But we go back to your Guerilla tactics. Doing those things without permission, what does that look like implementing some of these tactics?

Steve Gompertz: Yes, it depends but there's a lot of different approaches to this. One of my favorites is I call it hide the vegetables, which is sneak it in there without calling it what it is. I learned this from somebody else that had I great respect for. I went to a new company and they were taking me through a little training and I was doing CAPA training and he goes," You've got to read the SOP." And there's a form to fill out when you do CAPAs. And I go,"All right. Let me see if I understand what they're doing here." There's a section here and it says," All right. You need to go in here and you need to define the problem." All right. Great. And then the next section is,"Do you have any measurements to support that?" Okay. And then there's a section of," Give us an analysis of what those metrics are telling you." And all of a sudden the light bulb went on and I went," Did I just hear define, measure and analyze? DMA. Am I going to guess that the next section is something about what's the improvement?" Sure enough. There was buried in this process, but it didn't say Six Sigma anywhere and it didn't say to. I went and found the guy who wrote it and I said," Am I nuts? Does this sound a lot like Six Sigma?" And what I got from him was,"Shh! Nobody's supposed to realize that."

Etienne Nichols: That is genius.

Steve Gompertz: He was a master Black Belt and he goes," Because when I tried to sell the idea of going full blown Six Sigma, they push back on it." Didn't want to spend the money on whatever master Black Belt. So I've been spoon feeding it to them a little at a time. The idea is eventually this just becomes how the process works. And then when you start talking about this process, everybody goes," You mean that process we already do. What's different? We've been doing that for three years. Haven't we?" Yes. Now, we're just calling it by what it's supposed to be called. That's the hide the vegetables approach is that yeah, can you sneak pieces of it in there somewhere?

Etienne Nichols: That seems obvious. Once you say it just seems so obvious, but wow.

Steve Gompertz: Doesn't it? Yeah.

Etienne Nichols: Because I've been in situations where we had to read books on KATA for manufacturing or maybe we're going to implement Scrum for project management and everybody rolls their eyes and you're like," How do we do this?" But that makes total sense what you just said. Interesting.

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. There's all those... Whether it's Agile or Lean or whatever, all of these things, there's always somebody who can find some pushback for why that's an outdated concept and you don't want to go there or it's nothing new. Yeah, you just start hiding a few pieces in there and then it just becomes the norm. Eventually, maybe somebody like me figures it out and goes," Wait, I know what you're doing. It's okay. It's okay."

Etienne Nichols: One of the other things that I'm curious about is when you put these new things in place, what are the type of metrics that you should put in place to determine whether you did the right thing? 40 pages versus a trifold, that in and of itself seems like a no- brainer, an obvious thing. But at the same time, we like to measure certain things. What kind of metrics do you put on a quality management system?

Steve Gompertz: Boy, there's a big topic because it's something everybody gets wrong. They measure the wrong things. They measure what management wants to hear. They don't understand the intent. A good example, doc control. I'll tell a client," All right. As we're defining..." One thing I like to do is like to say," Hey, at that process layer, in that document, call it a QSP, quality system process document." There's going to be a section that says," What are we measuring in this process?". Every process I go," Well, what's the intent?" There's actually requirement for that. Because if you talk about manufacturing, cycle times, yield, all that... That stuff's really obvious. And then you go," So what's the measurement on doc control?" And I go," Oh. Well we've already measured that.""No." What are you measuring?" And I can guess what it is. It's how fast does it take to get a change request?

Etienne Nichols: That's what I was going to guess. Yeah.

Steve Gompertz: It's time. Because that's what management likes. They like efficiency. Costs less if it takes less time. I always go," Does that really tell you whether or not the process is effective?" Because I know lots of ways to speed it up by cutting corners. That's not going to make it more effective. It's going to make it less effective, but it's going to be fast. What I want to know is things like how many of those changes should have been avoidable. Let's categorize why that change was re- posted? Is it because it's an improvement to the document or to improve some feature of the device? Or is it a correction for something that should not have been there in the first place? Because then the metrics will tell us," Hey, maybe our review process, our change review process is not effective." People were maybe rubber stamping this stuff. Because we can always do another change request later and fix it until it becomes something well, when you missed it was actually a big deal. With my classes, I do a whole bunch of sections on minor errors that result in catastrophic failures, things like that. A lot of them come back to documentation. Something that I've missed in the documentation results in a rocket exploding on launch. I use a video of the for... That was back in the'80s or'90s, I think and it exploded 15 seconds after liftoff. I always ask everybody when they watch the video and this explodes into half a billion dollars lost. And I said," What was your first thought? Was it documentation error?" The crosswinds, something like that. It actually was when they did an investigation, it was a documentation error. They had put a requirement in the wrong place in the document. Therefore, the downstream users of that document, the 2A department did not see the requirement, therefore did not write a test within the protocol to test that situation that had actually occurred during the launch.

Etienne Nichols: Wow. That is...

Steve Gompertz: You put a sentence in the wrong part of the document and$ 500 million is lost.

Etienne Nichols: Wow.

Steve Gompertz: 500 million. And there's lots of examples of that, where there's small errors and things like that. Because people go," Why do we have to measure that control? Is that really an important process?" Can we focus on the really important ones? And go,"Well, I'll tell you what. If it isn't documented, it didn't happen. If it isn't documented right, things are going to go bad." The metrics thing takes a lot of thought and it can be challenging. It's got to change the mindset that you've got to get out of this. Well, this is what management's comfortable with and then that goes to oh, wait. Management is going to expect to see cycle time related metrics. Now we're going to come back and say," That's not what we're measuring anymore." You're back to that influence. You've got to sell them all. So how do you do that? If they go to management review and they want to see how fast their CR is going through and you don't immediately yank that out and go," No, we're going to show you this instead." Because that's when they're going to react badly. It's," We'll keep showing you that metric. But just on the side, we've been tracking this other metric that we thought might be curious and here's what we found." And then they start to get it and they go," Wait. 60% of our training requests shouldn't have been necessary? How much time did that take that we could have been spending on other things?" Again, hide the vegetables and they start to get used to those metrics. So yeah. It's starting to combine certain techniques and go... You don't want to just thrust it in there and go," I'm replacing it because I think I'm smarter than you." If you're going to create that defensiveness, it's... Like I talked before, if I had just shown up and said to an inspector," What do you think of this?" Versus," I've already replaced a big manual with this. You have to take it." You might not have that opportunity. And the same thing happened with metrics as well. The other way is not... Obviously, it's a topic that's been given as well around metrics and I do cover this in the Guerrilla tactic workshop is how to get those measurements because measuring things often creates fear. You need to typically measure somebody else's process and the people in that process automatically assume you're measuring them. How do you make it clear you're not measuring them.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. So they don't take it personally. Yeah.

Steve Gompertz: Right. Because there's always that age- old us versus them, production workers versus management. They're just looking for a way to fire us or make us work harder, that kind of thing. You have to be creative sometimes about your data collection methods. They have to be less obtrusive. It may require you turning some of those people that are in that process into part of your army to get them to understand what's in it for them, what's in both directly and indirect. How's it going to benefit me directly? Also, there's the indirect is well, if this helps the company get better, then the company can afford to give you a raise next year or the bonuses... That's the indirect. The direct is," Hey, that part of the process that you hate doing, if we can get the right numbers, we can demonstrate maybe why we don't need to do that." We've all seen that in production. Somebody's doing something and you go," I couldn't do that eight hours a day. That would drive me nuts."

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. Examples are already popping into my head. I'd better keep quiet. Names have been changed-

Steve Gompertz: We've seen enough people assembling things with tweezers. They're trying to thread something impossibly small through an impossibly small hole. I bet they don't enjoy doing that. I bet they'd rather be doing something else.

Etienne Nichols: Oh yeah. Yeah.

Steve Gompertz: But how do you make them sound? We're not eliminating that step to eliminate you. It's so that we can better utilize your skills on something else.

Etienne Nichols: That's a great point. Yeah. That something I guess every engineer has to go through that hazing from production at some point in their career.

Steve Gompertz: That's the problem. If you just go down there and show up and want to start measuring things, they can intentionally and unintentionally interrupt or affect your measurements. You get biased and now, it's not really good measurements. It's how are you going to do this so that if you need them to be the ones taking the measurements, they won't undermine you. Or if it can be done without direct interaction though, how do you not influence what's happening? Because there's always training management. How do you evaluate the effectiveness of training? A lot of companies go," Oh, well... Then after somebody takes the training, we observe them the next three times they do it." I go well, two things are going to possibly happen. Either they're going to do it perfectly because you're standing there watching them or they're going to mess it up because you're standing there watching them.

Etienne Nichols: The observation influences the measurement.

Steve Gompertz: Right. You need to get much more creative about how are you going to collect this information without you becoming part of the equation?

Etienne Nichols: Question, if we go back to earlier, when you were talking about the regulations and how that mindset shift allows you to ask the question," Why?" if we look at those words and we struggle, we don't like to be told what to do, but when you change your mindset and you start thinking," Why is this written? This has helped to adhere to better my business. I would want to be best practices." That makes sense to me from a looking at the regulations perspective. Now, if you think about metrics, now I don't know why I wouldn't have thought immediately when I think," How do I want to measure change orders?" My mind immediately guessed," Well, time." Because that's what I've seen measured in the past. How fast does it take to get a change order through? Do you have any recommendations or tips, best practices to change your mindset shift in that way as well to say okay, maybe a metric that immediately comes to mind, but how do we get to the metric that we really want? Like teach man to fish. What are your thoughts?

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. The key is how you define the problem. Like anything else, it starts with the requirements. If you don't define the problem correctly, then everything after that's going to be going down the wrong path, the same way as if you don't get the right requirements in place, everything you're going to build to design is going to be wrong. It's a step we often just go right past because we think the problem statement is easy because it's staring us in the face, isn't it? We go," No, not necessarily." That's what you observe. Those are the symptoms. That's not actually the problem. Again, it's a mindset... But spend a lot of time making sure you are working on the correct problem. The problem with doc control is not how long it takes to get a change request through, it's how many change requests were doing and why are we doing it. Are they value added changes versus things we should have been able to avoid? I was at a talk recently and somebody threw out a quote. It gets attributed to Albert Einstein, but it's one of those quotes that again, he never said. But it goes along the lines, somebody at some point must have said it but," If I had an hour to save the world, I'd spend 50 minutes figuring out what the issue was and 10 minutes implementing." That's the mindset. We tend to flip it. We spend 10 minutes defining the problem and then all the other effort goes into solving it. We could be solving the wrong thing. We've got to spend the time up front. Like I said, there's lots of... teaches a lot of this. You put that wrong problem statement in place and the example I've used with my students is if I state the problem of that a certain part is failing inspection too many times. The percentage inspection failures is too high. If I restate that as the problem, I know the solution really quickly. Let's not inspect that part.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. There you go.

Steve Gompertz: The metrics will come right back down where we want them.

Etienne Nichols: Great example.

Steve Gompertz: Well, that's not the problem. The problem isn't they fail inspection. The problem lies somewhere else. The problem is they're not within tolerances on a regular basis and therefore they're not going to fit in the assembly they're supposed to go into. All right, now let's do the five whys off of that. Often what it turns out to be is it has nothing to do with the inspection process, it's something much earlier and somewhere else is where the solution lies and it could be in those doc reviews.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. Yeah.

Steve Gompertz: It manifests itself in production or in incoming inspection. That's not where the solution is. The solution lies way earlier than that and maybe a completely different part of the world, in a different organization. That's where the solution is. I've had lots of experiences with that, where we're focusing on the wrong part of the process and then go," Actually, it's not the last step in the process, it's the first step. If it started there three months ago, we would've solved this problem."

Etienne Nichols: That's a great point. Yeah. I can remember in a manufacturing line where we were having failures and they immediately knew," Well, we know it's this problem up here that gets injection molded." So we go right up to that part and I just started walking up the line, starting at the problem, going back, just kind of thinking, because I'm like," What do I know? These guys are smarter than me." But the next part, I looked at I'm like," Would it have detected the failure here? No. Would it have detected the failure here? No. There were multiple places it could have landed and actually it was one of those spots where the failure occurred. It wasn't the actual part itself that they thought upstream." That's a really good point. One person had told me and I forget this. I wish it was always at the tip of my tongue, but the heart of the problem is the seed of the solution. It's just like you said, every time someone tells me, that it's the requirements, it's understanding the true problem statement, that that's really the key, I love that. That's a great point. It makes life easier. If you focus on the true problem, instead of like you said, fixing the length of change orders or fixing the fact that we're inspecting.

Steve Gompertz: Again, it's human nature and they say men are more inclined to do it. Is to jump right into the solutions. You've got to kind of take that step back and go," Am I solving the right thing? Am I listening?" There's probably a bunch of gender based things that I shouldn't get into here. But they often say," Men do the wrong thing. Think more like a woman maybe." But underlying that is this idea of yeah, don't make the assumptions. Get the actual context correct first.

Etienne Nichols: That's a great observation. I appreciate that observation. So one other point that I remembered you talking about and that was the seven habits of highly effective quality leaders. I wonder if you want to touch on that before we-

Steve Gompertz: No. Obviously, we don't have time to go too deep in that, but I'm a big fan of Stephen Covey's book, The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. I think it's still as high up on bestseller lists decades after it was written. He's dead. He had this big organization. But I went through the training. I'm not like... I don't have the tattoo.

Etienne Nichols: There's still time.

Steve Gompertz: But there's a lot of good stuff in there. At one point I was just sitting down one day and I was sort of lamenting... Actually, I did it first with project management. I was just sort of lamenting again, the number of people in project management that just had never gone through any sort of form of training and didn't understand that there's science and actual methodology to it. It's not just being good firefighters, that kind of thing. I was thinking about Coveys ideas and I said," Well, this habit actually is pretty similar to something you'd want to see in a good project. If I change the wording a little bit, it talks more to project management." Then I finally went," I wonder if I could do it for all seven."

Etienne Nichols: Oh man, yeah.

Steve Gompertz: And I did. I eventually worked up the Seven Habits of Effective Project Managers and then of course, as I got into quality, I went," Well, time to do it again. Let's see if I can do it through quality management, with quality leadership." And I was able to. Yeah, I'm stealing heavily from Steven Covey's ideas, but then turning it into things that are important from a quality leadership perspective. We've talked about some. This focus on requirements is one of the habits there, that it's just first and always is about requirements. We touched on the language of management. That's also one of the habits, is learning how to translate into management, which is dollars. That's the pretty typical thing that quality and any technical person gets into when they're trying to sell their ideas to management and they understand all the technical aspects of it and now they're going to try to sell it to somebody who's not as knowledgeable and doesn't necessarily care about the technical coolness of it, they want to see the business side. You have to be able to do that. I think it's Duran who has it twice in one of his books where he says, that's the key is that you have to learn to be bilingual. You have to be able to talk technical speak and you have to be able to talk business speak and then merge the two together and that's how you'll be influential. That's one of the seven habits I've got in there. So yeah, I just borrowed very heavily from Covey and said," What would the equivalent of this be if you were trying to be a quality leader?"

Etienne Nichols: I'm curious, what was the one that really made you start thinking about that? Do you remember?

Steve Gompertz: I think it was the requirements one. Because that's always been a big thing with me. It's similar to what I talk about, don't spend the time doing the problem. If you don't spend the time getting the requirements right, then everything else falls apart from that. It's the same thing and it's in the standards, it's in the regs, that requirements definition is not just about writing them down. It's not a brainstorming exercise and then you pat yourself on the back because now we have the requirements. There's all these other things they talk about. Like," Are you sure you've got them all? Are you sure they're not conflicting? Are you sure they're clear?" There's this evaluation piece that has to go on. That implies more time has to be spent upfront getting the requirements right. Why do they have that? Why is that in the standard of the reg? Because they understand if you don't get that point right, the rest of it doesn't really matter and you're going to do it wrong anyway.

Etienne Nichols: There's a tipping point, it feels like, in people's career. You mentioned one in your career where you finally had a handle on all of those things and so you could blaze the path that maybe others haven't gone through yet. I think that's super cool and very admirable. I feel like there was this not to the same extent, but there's a point in my career where I was frustrated with documentation. But then at one point, I looked at everything. I thought," Man, this is a little bit chaotic." We need a document that has just this much stuff, just so we can have it all in one nice place. I did that and I just was able to breathe the sigh of relief. Documentation can make your life easier, should and if it doesn't, then maybe you're not doing it right.

Steve Gompertz: The other really big key is that word system, quality management system. It's there for a reason. It didn't just give us the third letter in QMS because we need three letters to make it a decent acronym. It's there because that's really the key is you have to see it as a connection of things. If you're not understanding the connections I have this slide, I show my students, it's an electrical schematic. I said," These are your requirements to be met. It shows you the logic." And then I show a pile of parts that matches everything on the schematic. And I said that's actually compliance because there's a one for one relationship for every requirement that that schematic shows you, I can show you the part that goes there. But they're not touching each other. It's just a pile of parts. So nothing works until you assemble it into a system and then the intent of the schematic is realized. We do that in so many different ways where we just create this pile of parts, whether it's a pile of documents or an unstructured bill of material or things like that. We don't think about the relationships and that's why that word system is there. That's part of the idea of doing the process based thinking is to go," You need to see the bigger picture." Now, why don't we do that? It's hard. It's hard to see the big picture. 820, hopefully is going to go away pretty soon. But 820 has been based on the old version of 9001, the 1994 very siloed view. It's a pile of parts. It's a pile of processes and then we wonder why quality isn't come out of it. And then we go,"Yeah, well didn't. Well, 9001 get rewritten in 2000 to change that view to be more process- oriented?" Yes. But a lot of people never made that transition in their heads because it was too complex. Before, I could focus in on this process and then focus in on this process. Now, you're telling me, I can't just do this process without thinking about how it's connected to all the others and it's a proverbial thread on a sweater. Yeah. That's how a quality system works. When you pull the thread, the whole thing is going to come with it. I get it. It's hard, but you have... This comes back to why do you have to have the architecture well planned out so that before you pull the thread, you understand what it's connected to and now you can make better decisions about whether I want to make this change, how do I want to make this change? How is it going to propagate through the system?

Etienne Nichols: I feel like that was kind of a mic drop right there. Did you have anything else you want to add to our listeners, where they can find you, what you're doing?

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. These days I'm doing consulting, so I don't work for any particular med device company. I try to work for all of them if I can. But our company's called QRx Partners and it's very simple. www.Qrxpartners.com is the easiest way to find us.

Etienne Nichols: And I'll put a link in the show notes as well.

Steve Gompertz: Yeah. And my email is just as easy, steve. gompertz@qrxpartners.com. We actually have a feature on our website where we will let you ask us some questions for free. So you can touch base with an expert and get some free advice. And certainly get the conversation started and not start the clock on. And then as I mentioned, I do a lot of teaching. I'm not saying you have to go get a masters degree, but I teach a masters degree program here that's available remotely. But then I do these workshops, like The Guerilla Tactics. There are others that I do as well at various conferences, as standalone webinars or we can certainly deliver them individually to companies as needed.

Etienne Nichols: Awesome. Yeah. Well, that's great. I really appreciate it, all the things you're doing to make the industry a more streamlined place. It's much needed. And so I appreciate the work that you're doing. For those of you listening, you've been listening to the Global Medical Device podcast. We appreciate you listening. We are going to be having an ask- me- anything session with Steve in a few weeks as well. So I'll have a link in the show notes and we can stay tuned and we'll tell you a little bit more about that. Thank you so much for listening. We will see you next time.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Nick Tippmann is an experienced marketing professional lauded by colleagues, peers, and medical device professionals alike for his strategic contributions to Greenlight Guru from the time of the company’s inception. Previous to Greenlight Guru, he co-founded and led a media and event production company that was later...