In this comprehensive episode, Etienne Nichols and Mike Drues dive into the enlightening world of FDA inspections.

The duo decodes the essence of effective communication, the importance of managing expectations, and the art of proactive dialogue with the FDA.

They reveal insights that every MedTech professional must know, breaking down the philosophy, challenges, and expectations surrounding inspections, all while blending unique "Mike Drues isms" and Etienne's candid takes.

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some of the highlights of this episode include:

-

Grasping the art of proactive communication with the FDA, laying the foundation for regulatory success.

-

Delving into the essence of managing FDA's expectations during pivotal conversations.

-

Exploring the unpredictability of FDA inspections and the mantra of always being prepared.

-

Differentiating between inspections for class two/lower medical devices and class three devices.

-

Unpacking the role of FDA registration in attracting the FDA's attention for inspections.

-

Achieving the perfect equilibrium when providing information during inspections.

-

Navigating through concerns raised by FDA reviewers and appreciating the value of swift responses.

-

Addressing the nuanced gray areas, ranging from "sufficient investigation" to acknowledging and rectifying errors.

-

Unveiling real-world scenarios where complaints in medical device manufacturing are addressed effectively.

Links:

- GG Academy - use Promo Code "podcast25" for a 25% discount

- Greenlight Guru

- Vascular Sciences

- Michael Drues LinkedIn

- Etienne Nichols LinkedIn

*Interested in sponsoring an episode? Use this form and let us know!

Memorable quote:

""The solution to most problems is more communication, not less." - Mike Drues

Transcript

Etienne Nichols: Hey everyone. Welcome back to the Global Medical Device Podcast. My name is Etienne Nichols; I'm the host of today's podcast. Today with us is a familiar voice on the podcast, Mike Drews.

Mike, how are you doing today?

Mike Drues: I'm. Well, thank you, Etienne. And how are you doing?

Etienne Nichols: Well, it's good to be with you. I'm excited for this topic. When you proposed this one, I thought, well, it's not something I've really thought about before, what not to say to the FDA.

I'm sure you probably have some thought on why this topic even came to mind, and if not, it's okay. We can go into some of the thoughts that we wanted to hit. But I'm curious, what made you think of this topic?

Mike Drues: Well, I think it's a good question. As always, thank you for the opportunity to have this discussion with you and your audience.

I think a couple of reasons. First of all, this is one of those evergreen topics. This is a topic that all companies struggle with from time to time, regardless of what kind of a medical device you might be developing or marketing.

And also, and we can provide some references and the resources to the podcast afterwards. There were a few recent articles floating around the internet about this particular topic. So, I thought, yeah, gee, this would be a great topic to peel the layers of the onion back further.

And as always, I'll add some of my Mike Drues isms my Mike Drew's twist to this and share with you a number of examples. I think this will be a good discussion.

Etienne Nichols: Cool. So, one of the first things I guess when I think about communication is it's a two-way street. So, if we're thinking about what we shouldn't say to the FDA, maybe where we could start is what should we not answer or what can they not ask us?

Or what can they ask us? Maybe one or the other.

Mike Drues: Well, they can basically ask any question that they want, and we'll get into several examples.

But one place to start the conversation maybe is when can they ask you questions? And the way I think about it is there's sort of two phases to this. One on the manufacturing side, for example, when you have an FDA inspector come in to do a facility inspection, and that's sort of the gist of the examples that were floating around on the internet.

But the other thing that I think of is on the regulatory side, as part of a submission review process or as part of a pre submission meeting, obviously FDA can ask you questions during that time as well.

And as you know from our many conversations before, Etienne, there's no bigger fan of communication with the FDA than me. But on the other hand, I have a big caveat, and that is my regulatory mantra tell don't ask, lead don't follow.

So, I absolutely refuse to ask FDA a question, even in a pre-sub meeting. I will ask questions, but in a very controlled way. And if anybody is interested, we've done a lot of resources out there on pre subs and specifically asking the right kind of questions.

But I don't like to ask the FDA questions. Instead, I say to the FDA, here's what I'm planning on doing. These are the reasons why I'm doing it, these are the reasons why I'm not doing what I'm not doing, and so on and so on.

So bottom line, Etienne, and I hope this makes sense, whether it's on the regulatory side or pre-market or on the manufacturing quality side, post-market, my approach is virtually identical.

Just sort of a minor modification, but virtually identical. And the last thing that I'll say, Etienne, and then I'll share with you an example and we can bring up some discussion here.

I think it's important to manage FDA's expectations.

Whether you're dealing with a reviewer on the pre-market side or an inspector on the post market side, we have to manage their expectations. So, for example, one of the questions that I love to ask, either when I'm sitting on the FDA side of the table, for example, in a pre-sub meeting, or if I'm acting as a I don't really market myself as a mock auditor, but sometimes companies do ask me to come in and sort of kick the tires of the quality management system.

One of the most common questions, one of my favorite questions I love to ask is, regardless of what you're doing, why are you doing that and why are you doing it that way? And believe it or not, Etienne, sometimes I get a response. I do it this way because our procedures don't make any sense.

But that's what the procedure says. This is not a good response for anybody, let alone to say to somebody, to the FDA, if that's a legitimate concern. If you are following a procedure in your company as an employee, and for whatever reasons the procedure doesn't make sense, then you should bring that up to your company and say, hey, I'm doing this procedure, but I don't understand why it's being done this way. It doesn't seem to make sense.

Can we have a conversation about either providing a justification of why we need to do it this way, or alternatively, maybe we need to change the procedure? Right, but just to say, well, I do it this way because that's the way that people did before me, or it doesn't make any sense or whatever, it's just problematic on so many levels. And the other quick example I'll provide is I had a customer once during a manufacturing inspection that got pinged from the FDA.

They actually got a 43 observation from the FDA because the inspector came in, they noticed that the company was not following the industry standard in a particular area, and the company said, yes, you are correct, Mr. Or Mrs. Inspector, we are not following the standard, and here's why. Well, long story short, Etienne, and they actually came up with a method that was superior to the industry standard, that actually was better than the industry standard.

And they explained that to the inspector and the inspector said, oh, thank you for sharing that with me. That makes sense. By the way, here's your 43 observation. Anyway, that's the problem, because now we have just created not only have we not created incentives for companies to make things better, we've actually created disincentives for companies to make things better.

And I would like to think that whether you work on the regulatory side or the quality side or somewhere else, that that is not the purpose of regulation or the regulatory environment to create incentives to hold things back.

Anyway, any comments on anything that I just went through, Etienne, and I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Etienne Nichols: No, absolutely. One of the things I was thinking about is just the fact that that conversation takes place in two different places. Maybe at your manufacturing facility post-market, like you said, in an inspection, it's most common.

Or during the submission process, I could see neither of those being a good time to say, well, we're not sure, or we don't know why that is the case. I think we think of that intuitively with regulatory submissions.

You know you're going to be talking to the FDA and showing what you're doing. But during an inspection, we may not be as well versed all the personnel. So, this makes me think of applying this conversation to a broader audience.

So those of you listening, you may be thinking, oh yes, that's absolutely right. Well, you need to share that with all of the employees in your facility as well. That's one of the things that made me think of this needs to be shared with everybody on the floor.

We do things for a reason.

Mike Drues: Good point. And actually, that brings up another question. One of the many philosophies I've developed over the 30 years or so I've been playing this game is you can't anticipate every problem or every question, but you can certainly anticipate many of them.

Most of them. So, whether know prior to going to the FDA with a pre sub meeting or prior to an FDA inspection, I will always try to anticipate as many questions, as many problems as I can.

But as I just said, you can never anticipate all of them. So, in the event that somebody does ask you a question, whether it's in a pre-sub or a submission review or an inspection, it doesn't matter if they ask you a question that for whatever reasons you didn't anticipate that you cannot answer at that time.

I have a number of strategies to sort of kick the can down the road, so to speak. In other words, to buy myself some time. For example, I might say, gee, that's a terrific question.

However, the person that knows the most about that particular topic is not part of this meeting or is not available right now. Can we follow up with you and get that person in the room with us?

That's one. Or for example, another example is if you're doing a meeting with the FDA where you only have said, 1 hour and somebody asks you a question and you say, gee, that's a great question, but unfortunately, we only have a certain amount of time today.

And rather than trying to give you a short answer now, we'll follow up with you later with an appropriate answer. Bottom line, if FDA asks you a question that you can't answer or that you're not able to answer at the moment, don't feel that you absolutely have to right there.

Because chances are, and I've seen this happen before, people start throwing things out and you get yourself into more problems than you started with. Use some kind of a strategy like the ones that I just shared, to buy yourself some time.

Etienne Nichols: That's great.

I like those two. Very easy to remember and easy to apply.

If you don't have the answer, get the expertise in the room. If you don't have the answer, get more time to tell the answer. I love think about so if I'm thinking from a submission standpoint.

Okay, that's easy. I know I'm probably planning I may be even initiating that conversation with the FDA, but what about when the FDA comes to visit me? That's not always on my schedule.

When can I anticipate the FDA coming to visit or inspect me for those conversations?

Mike Drues: Yeah, great question, Etienne, and let me just flip it around real quick.

Do you think that FDA should announce let's just talk about manufacturing inspections for a moment here. Do you think that they should announce to the company in advance that call you up and say, oh, next Tuesday we're coming in to inspect your facility?

Do you think that they should do that?

Etienne Nichols: No, for the reason that if I want you to truly test my knowledge, it would likely be a pop quiz where you test my knowledge, not, hey, in three days I'm going to ask you this question, and I now have three days to research that.

But do you actually know the yeah, exactly.

Mike Drues: Exactly correct. And that's exactly how I feel, Etienne. And as a matter of fact,

if the true intent of an inspection is to find out how the company is doing on a normal or an average day, then what is the purpose? What is the point, other than perhaps simply scheduling convenience of FDA telling the company in advance?

In other words, I don't want the company, and this is not to be patronizing by any means, but I don't want the company to be under best behavior when the FDA comes in.

I want the FDA to see them under normal circumstances.

That's more realistic. It's kind of like I thought about this metaphor recently, Etienne, and it's kind of like when you prepare your taxes, when you're preparing your taxes, if IRS calls you up and says, Etienne, the next tax returns you're going to file. We're going to audit you. You might be a little more careful, a little more conservative than if they didn't tell you that in advance.

So, to me, the FDA telling a company in advance that they're coming to inspect them is kind of like the IRS telling you in advance before you file your tax return that we're going to audit you.

There's always the possibility of getting an audit, just like there's always the possibility of getting an inspection, but to be told it's going to happen next Tuesday, that's different. Okay, so coming back to your original question of when can FDA come to me?

Well, the short answer is like in everything in regulatory, it depends. For class two or lower medical devices, there is no inspection required as part of the clearance or the 510K or the de novo process in the class three universe. For example, for those in our audience that are working on PMA devices, one of the many criteria of getting a PMA is you have to have a pre-market manufacturing inspection.

But that's only in the class three universe. With one exception, because remember, Etienne, and good regulatory professionals know the rules, the best ones know the exceptions. In the de novo world, there was a recent change that allows in some cases, FDA to ask for a pre-market inspection of a de novo device, but that FDA can use their enforcement discretion to determine when that's necessary.

And it doesn't happen very often, but for the most part, PMA devices, you have to have an inspection before the product gets onto the market for five hundred and ten k, and de novo devices after.

More importantly, and this is what I tell my customers all the time, if you have a small company or a new medical device company that's developing maybe their first medical device, they don't have a medical device on the market yet.

When you get on FDA's radar, so to speak, is when you become FDA registered. In other words, prior to FDA registration, FDA will not inspect you because theoretically, you do not have a product on the market yet, therefore, why the heck would they inspect you?

It makes no sense. Sure, once you become FDA registered, that puts the company on FDA's radar, and assuming that we're in the class two or lower universe, you will be inspected at some point in time, whether it's next week, next month, next year, five years from now, some point in time, then you will be inspected. There's one other circumstance when FDA will do inspection. So, one I just mentioned, after FDA registration, that's the typical way, but there's another time that FDA will usually come in and do an inspection.

And by the way, this is typically an unannounced inspection. Can you guess when that might be, Etienne?

Etienne Nichols: Is that the guided forecast if someone blows a whistle?

Mike Drues: Well, it could be if somebody blows a whistle, but I was going to more broadly speaking, if there's a problem, if your device starts, for example, malfunctioning, if people start getting harmed and so on and so on, then FDA will come in and likely do an inspection, and most likely, they will not call you in advance and tell you that they're coming. So that would be an unannounced inspection. But typically, FDA does give you the courtesy, and it really is a courtesy to say, oh, by the way, Etienne, and we're planning on dropping by your company next Tuesday for a little visit.

Etienne Nichols: Something like, and I wonder how many companies truly take advantage of that luxury. I'm sure they do, but the mantra that I was always told was, stay ready, so you don't have to get ready.

But I'm sure a lot are getting ready during that time.

Mike Drues: The smarter ones are certainly getting ready, and by the way, the smarter ones are not waiting for FDA to call them up. And I'm telling you, I'm going to be here next Tuesday, but we'll talk about that in a couple of minutes.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, so you mentioned. So, the FDA will tell you in advance they're coming.

How should they prepare? If you get that, whether you wait until they tell you or before, like you said, the smarter ones are preparing long before or just staying ready.

When and how should you be preparing for that FDA inspection?

Mike Drues: Well, I would like to think, Etienne, and maybe I'm a little naive here, but I would like to think that preparing for an FDA inspection is a bit of an oxymoron to begin with, because at least in the theoretical world and I would like to think in the real world as well, that companies will always be ready for an FDA inspection. In other words, it should not be a source of anxiety or apprehension or nervousness or panic.

On the contrary, the company should be ready at any point in time for FDA or anybody else to come in and take a look at what they're doing, ask questions, and so on and so on.

So, I think, on a personal note, I think it's kind of unfortunate that so many people in our industry, they have this connotation that if and when the FDA comes to visit them, that it's an anxiety ridden experience, and it really shouldn't be.

It's not intended. You should always be prepared for an FDA inspection. Kind of like we've talked about recalls before, Etienne, kind of like having a prophylactic recall plan. In other words, don't wait for an actual recall of your device to happen and then ask yourself the question, oh gee, what do I do? No, that's terrible strategy. That's not even a strategy at all. In fact, be proactive, be prophylactic and come up with a recall plan in advance. Obviously, we all hope that none of our medical devices will ever have to go through a recall.

That goes without saying. But obviously recalls do happen. So, if and when it does happen, be prepared in advance for the recall. What was the old Boy Scout motto, Etienne?

And I was an Eagle Scout once upon a time. Be prepared, right? So be prepared in advance for an FDA inspection. Another thing that many companies do, obviously, to prepare for inspection is to have a mock audit, to have somebody come in, usually from the outside, and kind of play the role of the FDA inspector and go through their systems and ask questions and look for problems.

As I said earlier, I don't market myself as a mock auditor per se, but I do spend some of my time coming in when companies ask me to evaluate their quality management system and some of their processes and so on and so on.

So here are some things that you might want to look for when you're looking to hire a mock auditor. First of all, look for somebody kind of like an independent reviewer.

If our audience is familiar with the concept of the independent reviewer from the design review and by the way, I also work as an independent reviewer for design reviews. And one thing that I always want in the agreement is that no matter what I say to the company, I want to get paid.

Because you want an independent reviewer. You want, just like a mock auditor, you want them to be brutally honest. If you have an independent reviewer or if you have a mock auditor, come in and say, oh, you're doing a wonderful job, pat yourself on the back, have a parade.

I'm sorry, you might be ticking the box. The regulatory requirement, you are meeting the letter of the law, but you are not meeting the spirit of the law. You want somebody to literally be brutally honest and kind of like any of in our audience that are familiar on the clinical side.

An M&M conference, a morbidity and mortality conference that physicians and surgeons have all the time where you literally get into a room and you pull the gloves off and you duke it out.

You want to talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly. So, look for somebody that's going to be brutally honest.

When I ask people questions in audits or reviewing their QMS, I will give them the benefit of the doubt unless they give me reason or until they give me reason to do otherwise.

For example, and I know we like to talk about examples, Etienne, and so here's an example.

I had a company once, this was a few years ago, who was telling me how robust their document control system was, their document management system was. And just coincidentally I wish I could have planned this, but it was not.

It was just coincidentally. I happened to notice that they were projecting what was in that particular section of the QMS on the screen from the computer. And I also had a copy of it, a hard copy of it, in a binder in front of me.

I just happened to notice, coincidentally, that the rev date on the bottom of what was on the screen was different than the rev date that was printed on the bottom of my printed manual.

They just destroyed all of their credibility when it comes to not just how robust their document management system was, because clearly it wasn't robust. It wasn't working for such a bad thing.

But I've learned that if the company is making such a small, seemingly simple, maybe even a trivial mistake in this area, what other mistakes might they be making in other areas that might not be so simple, that might not be so trivial? So, once again, I will give the people the benefit of doubt unless and until they give me reason to think otherwise.

And then at that point, I will pounce.

Now, how many other reviewers or inspectors do that? I don't know. But that's my approach. Does that make sense?

Etienne Nichols: I think that's good advice. When choosing a mock auditor, we don't talk about that a lot or very often or choosing an independent reviewer. I think that's really good advice. I really like the example you used with doing your taxes.

I remember getting audited. I never thought this was happening to me. In 2018, I was audited, having done my own taxes all my life. I like to follow the forms, and I had messed up.

I look back on that and I think, would I have done anything differently? I don't know. But anymore, I assume I will be audited, so everything stays the same. But to your point, you should assume you will be inspected because you will be.

And that's really good advice. Be ready so you don't have to get ready. What about the actual conversation? So, we're preparing for the conversation by just being ready from a manufacturing standpoint, from a regulatory submission standpoint.

And you did give some advice on how to answer some questions that maybe we don't have the answer to right off the top of our head. We need to get the expert in the room, get some extra time on the calendar.

What about some suggestions or general guidelines in answering those questions when the time comes?

Mike Drues: Yeah, great question, Etienne. And a lot of the advice that I'm giving today, as well as a lot of the regulatory and quality advice that I give in other areas, is based not just on my regulatory or quality experience, but on my expert witness experience.

Because as I've mentioned before, Etienne and I spend a growing part of my time working as an expert witness in medical device product liability cases. And so, for example, one of the things that I do with my attorneys prior to a deposition or being testifying in a court is do some role play where the attorney will play opposing counsel and ask me questions and see how I respond.

And then we have to be a little careful what I say here, but how I should best wordsmith my responses and so on. I would suggest that companies, when they prepare for an inspection and as we talked about earlier, Etienne, and you should always be prepared.

So maybe this is something that you do on a regular basis, perhaps a couple of times a year, is you do some role playing and you have somebody, ideally somebody from the outside.

I don't think it's a good idea to have somebody from in your company do this, but somebody from the outside, whether it's an independent consultant like me or somebody else, come in and do some role playing.

And I work as a consultant for the FDA. So, I will temporarily put my FDA hat on and ask you questions about, for example, why are you doing something a certain way?

And if the person is like the deer in the headlights or they say, well, that's what the procedure says, but it doesn't make any sense, that's a problem. And at least if you do it in this practice environment, it's a little safer than if you do it when FDA is in the room, so to speak.

That's obviously a more controlled environment. Another piece of advice, and this is general advice, Etienne, and you may have heard this before, but I've learned it not just in my FDA inspection experience, but in my regulatory experience and in my expert witness experience as well.

And that is answer the question that was asked, and only that question. In other words, don't go beyond don't provide additional information. And I'll be honest with you, Etienne, I have a very difficult time with this one myself, because I usually will provide additional information that was not asked for.

And I remember it might have been my very first deposition. I learned that lesson the hard way. I mentioned something that was not in my expert witness report as an anecdotal example, and opposing counsel just pounced like a lion.

So, I learned that not to do that again. But here's a classic example. If I ask you the question, Etienne, and what time is it? How would you respond?

Etienne Nichols: 12:34 CST.

Mike Drues: Oh, I'm sorry, forget I asked you that question.

Etienne Nichols: Erase my mic.

Mike Drues: I should have asked you the question, Etienne, and do you know what time it is?

Etienne Nichols: Yes.

Mike Drues: Do you know what time it is? And if you would have and many people would look at your watch and say, 12:34 CST, that's great, but you're not answering the question that I asked. I asked the question; do you know what time it is? And the proper response would be, yes, I do, or no, I don't.

Right. So that's a very simple but it's a very powerful example. I'm sorry, I screwed up the example.

Etienne Nichols: No, I'm glad you bring up that example. It's interesting. Well, first of all, the fact that you do podcasts and the expert witness has got to give your brain a bit of just overheat it sometimes, because oftentimes I tell people when we're doing podcasts, now answer the question you wish I had asked so that we could have a good conversation.

But that's just not what you do during an inspection.

Mike Drues: I can get away with that in a podcast, Etienne, and politicians get away with it all the time. But in a deposition or in a trial, a good attorney on opposing counsel, they won't let you get away with that.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. And so, extending that logic, those are kind of two extremes. We have just a conversation that we can have. We have a deposition or a trial. Now, where on that spectrum does an FDA inspector fall?

Do I treat it like the yes, I know what time it is? At some point, will they see this guy is know there's a human element there? But what are your thoughts?

Mike Drues: That's a very good question. Thank you for asking that, Etienne. And I think in that spectrum of FDA. Inspector versus expert witness. I'm going to be closer to the inspection side. In other words, legal. I will provide the minimal amount of information. If I think it's necessary to provide a little additional information, then I might do that.

I'm not going to worry quite so much about getting pounced on like I would from opposing counsel in a deposition, but nonetheless, I still would stick with the advice of answering the question that was asked and not going beyond that. But again, I'll be the first to admit I sometimes have a difficult time doing that myself.

Etienne Nichols: It makes me think of an example we had from engineering where there are some guys had the T shirt; anyone can extrapolate engineers interpolate. And so, when we're thinking of things, if an inspector is thinking, I'm going to ask this question so that I can then ask this question, if you answer ahead of what he's asking, you may not be going down the train that he's going. So, it's not necessarily disrespectful. It's more respectful to answer the question so that he can proceed down his train of thought rather than interpolate or extrapolate.

Mike Drues: It's actually, it's interesting that you phrased it that way, Etienne. And, because to me, what it sounds like you're describing essentially is the Socratic method, something that I use all the time.

In other words, Socrates was a very smart guy. Whenever somebody asked Socrates a question, he would never answer it with an answer. He would always respond with a question. But it was a leading question, such that after asking you a series of these leading questions, he got you to ultimately go where he wanted you to go, but you felt as if you got there yourself. It's an extraordinarily effective communication technique. I use it in my teaching all the time. I use it in my consulting all the time.

And if I'm an FDA consultant, I'll use it in the FDA all the time as well. And speaking of questions, one other piece of advice that I'll share with our audience, Etienne and another thing that I've learned from my expert witness work and from my FDA work as well, is before you answer the question, if you're not sure you completely understand the question or why it's being asked, feel free to ask a clarifying question. For example, what specifically are you looking for? Or why are you asking me for this particular information?

There's absolutely nothing wrong with asking a clarifying question, and it's better for you to really understand the question so that you can give the proper answer than to just kind of guess what you think is being meant.

And that's like throwing darts at a dartboard with a blindfold on. And I see this not just in FDA inspections, Etienne. And, but I see this in pre-market reviews all the time when FDA comes back.

For example, after a company makes a submission of a 510K or a PMA with an additional information, request an air FDA. To their credit, they will script out their questions as best as they can.

But sometimes when the reader, the company, reads the question, they're not exactly sure what the question is asking, or they're not exactly sure why the question is being asked. So, I will frequently ask for FDA to have a quick I prefer to do it as a meeting or if necessary, via email to clarify exactly what information are you looking for or why are you asking this question? So, asking a clarifying question before providing the answer is a good strategy and another way that you could use that technique.

Going back to what we talked about a moment ago, Etienne, and if somebody asks you a question that you can't answer, if you don't think you could ever answer it, then it's good to use one of those strategies that I mentioned earlier.

Sure, if you think that you can answer it, but you need a few seconds to think about it to craft your answer. Here's a strategy ask a clarifying question. Even though you might think you already understand the question, ask yourself a clarifying question to buy yourself a little bit of time while the person is responding to your clarifying question, then you can be thinking about how you're going to respond to their original question. So, as you've heard me talk about, Etienne, and before, I characterize the relationship between the company and the FDA as a poker game in every sense of the word, this is just another way of playing that game.

I won't go so far as to say manipulating the game, but playing the game, winning the game, is a heck of a lot more complicated than just simply reading and understanding the rules of the game.

Etienne Nichols: Right? It's not single deck blackjack, it's poker. Absolutely.

Mike Drues: That's a fabulous metaphor. I have to use that one myself.

Etienne Nichols: Okay, we've got the questions that maybe we know the answer and so forth, or maybe we need to buy some time. But what about if a problem is found? How do we handle that?

Mike Drues: Yeah, great question. And look, I would like to think that if you're doing all the things properly that there wouldn't be any problems. But if everybody did everything the way they should, then we probably wouldn't need FDA inspections.

We probably wouldn't need an FDA. So given that companies do sometimes have problems, most of the time, inadvertently or by mistake, occasionally not, the question is what to do. First of all, kind of like we just talked about before in terms of clarifying question, make sure you understand exactly what the problem is.

In other words, or what the concern is. I don't want to necessarily use the word problem all the time because problem sort of automatically assumes a negative connotation. So, what is the concern or what is the question that the reviewer has here?

Make sure that you understand exactly what that concern or that discrepancy is.

Once you do that, unless this is an absolutely urgent matter, in other words, unless, for example, you're in the class three universe, you're making totally implantable artificial hearts, and all of a sudden, the last several devices that were implanted failed and the people died.

Okay, that's an extreme case, and that's something that you need to respond to, like, ASAP.

But in most times, in medical devices, it's not so urgent, it's not so extreme. So don't feel that you have to solve the problem right then and there. If it's a simple problem, if it's just a matter of paperwork, well, the information that you're looking for is in this other document here, let me give it to you. Okay, that's fine. That's an easy concern to address, but most concerns, certainly the concerns that I get involved with are a little more complicated than that.

And so, again, buy yourself some time to say, okay, we'll investigate this, we'll put together a response, and we'll get back to you. Don't feel like you have to address it.

And most of the time, inspections, when an FDA comes in for an inspection, most of the time the inspector is not there for just like 30 minutes or an hour.

Most of the time they're there for maybe a few days, in some cases a few weeks. So, if they bring up concern and it's something that you can deal with, but you need a little bit of time, say, we'll get back to you tomorrow, or if there's a weekend, take advantage of the weekend. If you need to pull your team in on a Saturday to come up with a, you know, we'll get back to you on that on, unless, you know, there's an eminent threat of harm, you don't have to solve the problem right away.

And then the other thing that I'll say in this regard at the end, because this is a suggestion that I've made to the FDA many times over the years, which they still have not implemented.

We don't have a good process in place for when companies do get 43 observations or worse, warning letters for the company to address their proposed solution to the problem with FDA in advance, to make sure that both the company as well as the FDA, agree that, yes, this isn't a reasonable and appropriate solution for this particular problem.

This is one of the reasons why when companies get 43s or warning letters sometimes, and I have many examples where the same company will get the same 43 or the same warning letter, sometimes multiple times over and over again.

And part of the reason may be because either they're not addressing the concern, and if they are, and if they're not, then shame on them.

Those people shouldn't be in this business. Or if they are addressing the concern, but they're addressing it inappropriately or not effectively, then they're going to be getting another 43 observation or another warning letter in the future, it stands to reason.

So, we need a way. I've suggested to the FDA we create another form of a pre-submission meeting or a pre-sub having to deal with manufacturing issues exactly like this. I had a company recently who got a 43 observation in a manufacturing inspection because FDA said they did not investigate all complaints equally, which is true. And we said to the FDA, inspector, yes, you're exactly right. Let us explain why. When you think about it, investigating all complaints equally doesn't make any sense.

We have a system previously spelled out in detail in our quality management system, which describes which complaints get investigated and which do not, and in what sort of a priority and what are the steps, and so on and so on.

Kind of like the metaphor that I often like to use, Etienne, and if you go to the emergency room, a patient having a heart attack is supposed to get treated first over a patient that has a splinter in their finger.

We use a triage system. So, this particular company, they made a respiratory device. If the complaint was about a valve on the device not working, or a gauge on the device not being accurate or something like that, okay, that's a no brainer that needs to be investigated, and that needs to be investigated right away.

But on the other hand, if somebody calls in with a complaint that says, well, there's a scratch on the outer housing of the device, and it has no impact of safety, efficacy, performance, any of that kind of stuff, then what the heck is the purpose of investigating that?

You know, treating it equal to a complaint, know, a valve or the gauge on the device is not working. The point of this example, Etienne, and is very simple.

If we had an opportunity to present this to the FDA in advance. I E prophylactically like I have suggested many times, a form of a pre sub meeting. We create a new type of a pre sub for manufacturing issues like this, where we could present this plan to the FDA.

Prophylactically then we would have avoided all of these. Know, it goes back to, I think, what I said earlier. The solution to most problems is more communication, not less.

Etienne Nichols: One of the things that you made me think of when you were talking about, if someone asks you a question or you gave the advice of truly understanding what the problem is before answering, perhaps if there's an issue or maybe it's just a concern, truly understanding that, and then maybe buying some time and investigating that.

One of the things I thought of was, when we give this advice, one other tiny little layer I would put on is some people need to learn what it means to investigate a problem.

If we're expecting them to come back the next day during that inspection period, maybe it's two, three days, we may come back with what we think is a solution, but really a lot of us just don't know how to do proper investigation.

Root cause analysis.

Mike Drues: I could not agree with you more. And this is a topic of a whole different it is discussion. You may remember one of our recent podcasts from a few months ago.

We discussed some of the most common reasons why companies get 483 and warning letters from FDA, and one of them was for not investigating complaints. If there's simply no investigation whatsoever, that's a difficult thing to excuse.

What usually happens is it's not a sufficient investigation. And now you get into that whole infinite gray area of what constitutes a sufficient investigation.

And that's where it gets interesting. But the last piece of advice in this area I would give Etienne, and then I think we probably can wrap this up sure. Is if FDA brings up a concern or brings up a problem that you recognize is actually a mistake, like for example, I'll use the complaint example. Like, for example, they say, well, here's a record of a complaint coming in on such and such a day. I can't see any record of you investigating this complaint.

What the heck is going on here? And remember, Etienne, and as I said earlier, I will give people the benefit of the doubt until they give me cause. Otherwise, if they say, oh, I'm sorry, that's on this particular document over here, you just didn't see, that fine, not a problem.

But if you recognize there's a complaint that for whatever reason fell through the cracks and you didn't investigate it, would you say something like, gee, that's interesting, we should have investigated that.

Now you're on slippery slope here, right. So, this is another one of those times where I would probably try to buy myself some time and say, let us look into this if you really want. Here's an interesting example.

Etienne Nichols: Whenever I see that smile, I want to hear it.

Mike Drues: We've talked about, and you're very familiar with Kappa's corrective actions, preventative actions, which, by the way, I've said on many podcasts, I think it's back *** words. I think we should call it a protective sorry, a preventive action.

Corrective action. But nonetheless, would you say, gee, that complaint apparently didn't get investigated. Perhaps we should consider opening a Kappa. I think that's a very legitimate question to ask within your company. I'm not sure that I would bring that up when the FDA inspector is standing in the room, but there could be an advantage of doing that.

I'm not sure. But anyway, something to some of that.

Etienne Nichols: Goes back to the softer skills. But I agree, considering it up on the spectrum, closer to the legal side, just keeping that in mind, I think is good advice. Like you said earlier, exactly what else is important? I know we're about out of time. Did we miss anything that you wanted to cover?

Mike Drues: Well, like all the topics that we talk about, Etienne and I think this is a great start to the conversation, but we're just scratching the surface, the devils and the details just to kind of go through and recap what I thought were some of the highlights and more important takeaways from today's conversation. And then Etienne and I would love to hear what you think were the important things.

But a couple of things. First of all, as we discussed, always be prepared for an inspection. Traditionally, FDA will give you the courtesy of letting you know in advance when they're coming, but they don't have to do that.

And as I said earlier, if there are problems with your device, they won't do that. They will just show up unannounced on your door. Hey, knock on your door. Hi, it's Mike from the know. Invite me in to take a look at everything and pay attention not just to what's going on with your particular device, but in your competitors’ devices as well.

This is something that I don't think I mentioned before, but it's worth noting here if there are problems with other similar devices, for example, if your device is on the market as a, you showed the FDA that your device is substantially equivalent to your competitor's device.

If it turns out that your competitor's device has problems and maybe that device is under recall, don't be surprised if FDA comes knocking on your door unexpectedly and says, hey, we noticed that your competitor, who by the way, has a very similar device to you, is having problems.

We want to come in and take a look at what you're doing to make sure that those problems don't happen to you, right? So that can does happen, and to be honest with you, that's FDA doing their job.

That's what they're getting paid to do. Most important, and this is going to sound a little trite, perhaps maybe a bit even naive, but most important, if you're doing what you need to do, not just what the regulation requires you to do, because as we've talked about before, that's the academic equivalent of being a C student.

If you're doing what you need to do and if you can prove, if you have objective evidence that you're doing what you need to do and if you can explain or rationalize or defend not just what you're doing, what you need to do, but what you're not doing and why you don't need to do that if you can do those three things, if you're doing what you need to do, if you can prove you have objective evidence that you're doing it. And if you can explain or rationalize when somebody challenges you, why are you doing it this way?

Then you shouldn't have any problems at all. And you should welcome FDA or anybody else to come into your facility at any time because you're well prepared you have explanations, you have evidence, and I have to be a little careful what I say here, Etienne. And when I'm working on the FDA side of the table, I will frequently ask the company a question, even if I agree with what they're doing.

I will ask them a question like, why are you doing it this way? And if they give me some explanation that's based on some logic from engineering or medicine that makes sense to me, then I will give them a lot more latitude, a lot more leeway.

But if they give me a response like, well, I'm doing this because it's required, or worse, I'm doing this because the 50 other companies that work in this area do it that way, therefore I'm doing it that way, I'm sorry.

I'll be all over them like a cheap suit because that's not the way this game is supposed to be played.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, to your earlier point about going above and beyond, I think sometimes we throw around the word standard so much that we forget in this industry what the classical definition is, which is just a baseline expectation, normal behavior, and so it's okay to go above and beyond the standard.

I think we forget that sometimes.

Mike Drues: Exactly. Good point. There are so many times where something is considered the gold standard, and gold standard doesn't necessarily mean that it's good or that it works.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I know. We're out of time. Thank you so much, Mike. I really appreciate you coming on the episode and we'll let you get back to it.

Mike Drues: Thank you.

Etienne Nichols: Thank you so much for listening. If you enjoyed this episode, reach out and let us know either on LinkedIn or I'd personally love to hear from you via email.

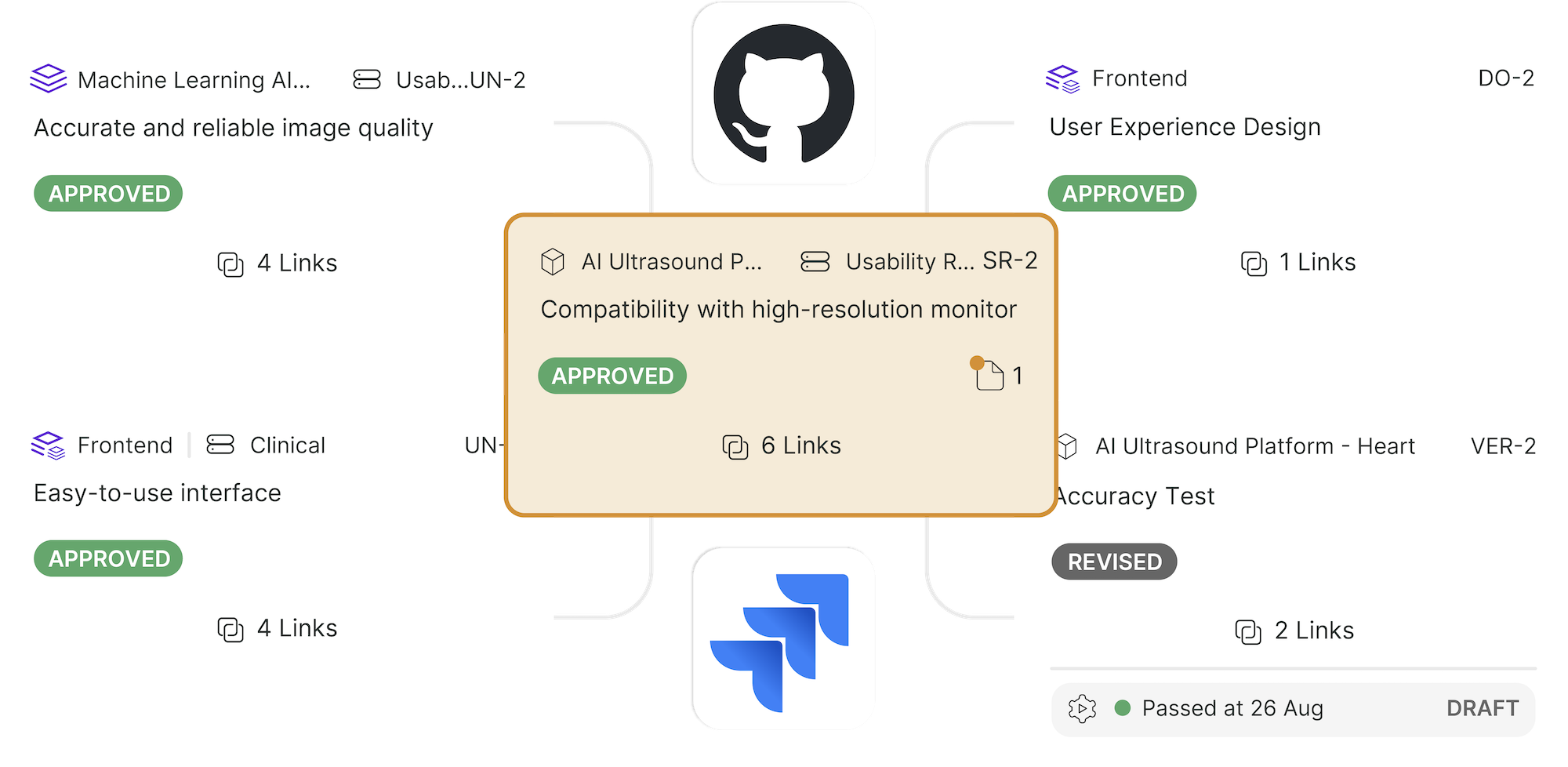

Check us out if you're interested in learning about our software built for MedTech. Whether it's our document management system, our Kappa management system, the design controls risk management system, or our electronic data capture for clinical investigations, this is software built by MedTech professionals for MedTech professionals. You can check it out at www.Greenlight.Guru or check the show notes for a link. Thanks so much for stopping in. Lastly, please consider leaving us a review on iTunes. It helps others find us. It lets us know how we're doing. We appreciate any comments that you may have. Thank you so much. Take care.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

.png)

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...