In this insightful episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, host Etienne Nichols engages with Morven Shearlaw, co-founder of Fearsome, in a thought-provoking discussion on the essence of human-centered design in medical devices.

Delve into the importance of understanding user needs beyond surface-level assumptions and learn how Fearsome's approach to product development is setting new standards in MedTech.

From Glasgow's design desks to global market impacts, this episode is a deep dive into making MedTech better by truly connecting with the end-user experience.

Interested in sponsoring an episode? Click here to learn more!

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Like this episode? Subscribe today on iTunes or Spotify.

Some of the highlights of this episode include:

- The Pitfalls of Premature Solutions: Morven emphasizes the need for extensive user understanding before jumping to design conclusions, challenging the common industry haste to offer solutions.

- The Evolution of Fearsome: Morven shares the growth story of Fearsome from a broad design firm to a specialized MedTech developer, emphasizing the value of a diverse industry background.

- The Nuances of Usability: The conversation reveals the stark differences between consumer product design and medical devices, particularly the rigorous safety and risk management requirements in MedTech.

- Defining the User: A deep dive into identifying the 'user' in medical device design, considering all stakeholders, from clinicians to patients and even those involved in device maintenance.

- Real-world Feedback and Its Impact: Morven recounts a powerful anecdote where candid feedback from clinicians significantly redirected a product's development path.

- The Risk and Reward of Human Factors: An exploration of how human factors, beyond safety, can become a competitive edge and a catalyst for enjoyable product experiences.

- Regulatory Hurdles and Human-Centered Design: A critical look at the intersection of regulatory standards and human-centered design, advocating for earlier and more integrated human factors consideration.

Links:

Memorable quote:

"Quality management is about quality, it's not just about proving that you can sell in the market because you've got a certain certification." - Morven Shearlaw

Transcript

Etienne Nichols: Hey everyone. Welcome back to the podcast. My name is Etienne Nichols. I'm the host of today's episode, and with me today is Morven Shearlaw. Super excited to have her with us. She's the co-founder of Fearsome.

Maybe I'll just hand the mic to you to see how you're doing, and you want to give a little bit of your origin story and maybe some of what you're doing over there at Fearsome.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, absolutely. So nice to meet you, SN, and thanks for having me on.

So, fearsome, we are a design and development agency specializing in medical devices. So, we help our customers bring their innovations to the market. So, we help them design, develop, build, test, and ultimately, hopefully launch into the marketplace. We're based in Glasgow, in Scotland. I would say sunny Scotland, but, you know, that's only every so often.

And as you mentioned, I'm co-founder of the business. So, there's two of us started the business around about 20 years ago. We have a team of around about 20. We're actually growing all the time. Somebody started yesterday. It is definitely a busy time for us.

And actually, this is the main thing I've ever done. I came out of university, did a few sorts of small freelance jobs. I did design engineering at university. Always loved making and building things, understanding how things work, and also the creative side. So, I really love drawing, I love design, I love looking at nice things.

So, yeah, came out of university, it was around about 2000. So, it's quite a long time ago and there wasn't a huge amount of job design opportunities up in Scotland. Very sort of London southeast focused.

It's different now, it's completely different landscape now. But myself and Alan, the other co-founder, decided that we would just sort of strike out and see if we could just make a go of it. That was, know your living costs weren't so expensive, you're happy to eat noodles, all that kind of stuff.

So, we started as a broader design firm. So basically, we did any kind of job that people asked us to do because we were trying to make money and build a business. And we've just kind of grown organically since then. The last ten years we've started to focus towards medical devices and that's primarily what we do now.

But the experience of all the other industries has been really useful in development of the company, building expertise and sort of understanding of different types of manufacturing regulations. So, we've got kind of quite a broad background, but we're now really focused on medical devices.

But I think the broadness has really helped us in thinking slightly laterally, sometimes not being too niche and focused on things. So, yeah, that's a little bit of the origin story. I don't know if that was too much detail or not enough detail.

Etienne Nichols: Well, it's enough to make me curious about a few things. And I know we want to get to the topic of usability and focusing on a human centered medical device design.

So, I'll just go ahead and throw that out there, my preview to the overall topic. But I do want to ask a little bit of question because that actually is really valuable, having worked in those other industries, or at least I can potentially see it being really valuable.

I'm curious, in 20 years, you've probably seen so many different changes. It was 1996, I think the design controls came out, so it's still probably relatively new. When you came out, the differences in those other industries and medical devices, what are some of the stark things that stand out in your mind?

Morven Shearlaw: So, in the other industries, we did a lot of work in other heavily regulated industries, so there's quite a lot of parallels between there's thing called ATEX, which is basically when things are designed to be used in explosive environments, used on oil rigs or in submarines. So obviously safety is a huge factor.

And I think the starkest difference is, I think the rigor that you have to go through when you're looking at a product that's going to be used in a consumer setting and what you need to prove the safety factors.

Yeah, I think that's probably the starkest difference between the other industries and medical devices. But like I said, we were working in industries where something goes on fire, you've got a serious problem. So, you have to still regulated. Yeah, exactly.

Okay. And I think maybe access to end users as well sometimes is easier in other industries if you want to talk with nurses, clinicians, they're busy people or there's confidentiality issues.

So sometimes in other industries it's easier just go out and find someone that would use that type of product. But if you're talking about a niche medical product, then your pool of users is smaller. You're going to have a tougher time kind of finding those experts to get that input.

Etienne Nichols: Well, let's use that as a segue then, because if we want to talk about a human centered medical device, something that is designed with the user in mind, who do we define as that user? You mentioned clinicians and nurses. Sometimes I think of if I have a device that's going to be used in the home, just the user, but what is the scope of my end user when you think about that?

Morven Shearlaw: Yes. So, a thing that we would always try and introduce as early into a project or product development is figuring out who the end users are but also making sure we're talking to as many stakeholders within that product ecosystem.

So, like a product, I like to think about human factors. It's product, people and place that's used in. So, you have to consider the environment it's used in, the systems, the organizational systems and the people that are involved in that product.

So those could be the end user. So, it could be a clinician if it's a surgical device. But there's also people that are going to be cleaning that. The system of like how is this reused?

How is it made clean and suitable to be used the next time without any infection risk? You've then got another layer of like, well, who's actually buying the device? Who's making a decision about buying that sort of commercial side?

And then obviously the patient often is a user as well. So, as healthcare is changing and more of it's trying to get sort of being pushed towards the home, people being looked after in the home environment, then the patient become the primary user of these devices.

So, we would always do a kind of an exercise at the beginning. It just goes even before the product exists or the concept exists, say right here are all the people involved in it.

We need to speak to as many of these people as possible just to understand what the issues are going to be, what the requirements are going to be. Is there going to be some budgetary thing that basically means the product can only ever cost this much.

If it's going to be too expensive, it will just be dead in the water. So, we try to think as broadly about human factors as possible, not just what color is the button going to be on the device.

It's really about who all is involved in this product lifecycle, from it being used and being purchased, right up to it being potentially decommissioned or refurbished.

It's always a challenge sort of identifying all the main stakeholders because often you have to speak to people to then understand, all right, that person is also involved in this process, and then we need to find some of them. But to be honest with you, that's the stuff I really enjoy, that sort of little puzzle, figuring out where the important areas where you're going to find the nuggets that are really going to help you develop the products and ultimately, hopefully develop a commercially successful product.

Etienne Nichols: I love that.

Okay, there's a couple of things I want to do. I actually want to do two different things.

Maybe first, what we should do to serve the listeners best. If we zoom out and think of it from end to end, maybe if we could do a very skim flyover and you kind of mentioned a little bit about determining who the users are, but what is the overall process from a human centered aspect of the design and development of a medical device?

What are the different phases or stages we need to do? That's one thought I want to have, and I don't want to throw too much at you, but that's one thing I want to cover quickly or however much depth you want to go.

The other thought, and you can punt on this if you want. You can say, no, I don't know if I want to go there. If I came up with an idea for a medical device, like right now, could you walk me through the different stages? And we'll just say, hey, pinned, we're going to do this. And give a fun example. Which one would you want to do?

Any thoughts?

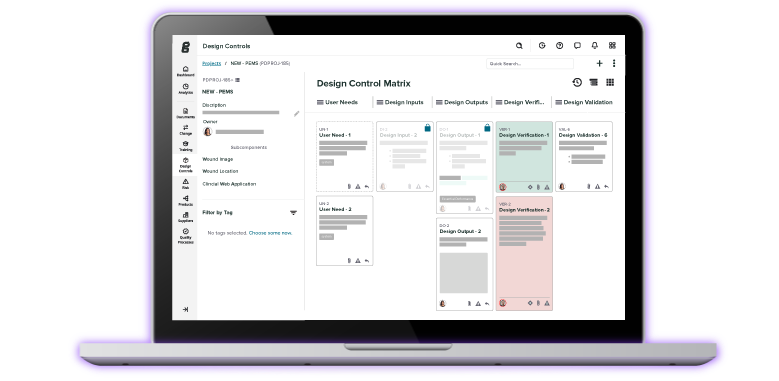

Morven Shearlaw: Well, I mean, they're broadly sort of two sides of the same coin. In that medical device development, you start with your user needs, which gives you your design inputs, which then gives you your design outputs, which is your design, which you then test against your user needs.

And then you verify that you've got something that is suitable and safe and can be launched into the market.

So that front end bit all about the user needs, that's really the starting point. So, you've got to start with who's going to be using it, why are they going to be using it, who are they going to be using it on?

But then you've also got like marketing input. So, if we are working with a customer, they will probably have some idea of the marketplace that they're working in and they will probably have some kind of indication of we are looking to enter this particular bit of the market, I.

Etienne, we want to make a device that is competitive with this other range of devices, or maybe they've got a high-end product, and they want to bring in a sort of a more accessible financially product. So those are part of your design inputs and your user needs. So, your users, from our point of view, we are also our customers, our stakeholders in a product.

It's not just, that's true customers, their requirements of what the product needs to do for them as a business are huge drivers to what the device will be.

So, if you were to come to us, and I'm delighted to do any design project with you, come to us with an idea for a medical product, we would probably want to take a step back and go, well, why this thing?

Where's the innovation lying? Why are you trying to do it this way? And instead of just running with that concept going backwards and going into quite deeply into the users, deeply into who's going to be using it, what else is on the marketplace?

How else can you solve this problem?

Why would there be a market for this particular concept? Because a product doesn't exist in a vacuum. All the things need to be right.

There needs to be a market for it, and that market needs to be large enough to sustain it.

You need to make sure the intellectual property as well. That's a huge factor. Are there other things out there that are doing a similar thing? Is there a bigger player that's already operating in that field?

That actually might just cost you anyway.

But none of these are necessarily questions you can answer, but you have to make sure that you're probing all these things before going on a certain path. Because medical device development, any product development is expensive.

It takes a long time.

The regulatory aspects mean that it takes a certain amount of time. You're paying people to develop things for you, whether you're doing it in house or using a subcontractor or a partnership, there's a lot of time and effort goes into developing things that are safe and manufacturable, even just investment in manufacturing.

The further you go, the more money you spend and then the more committed you are as well. So better to test out the concepts before they're really even a concept, because you can do a lot of things like that where you go out and we've done things where we've gone to clinicians with bits of cardboard to represent a screen.

And it's like, well, could it sit here, or could it sit over here? And ten-minute conversation and you've already advanced the thinking hugely, or even just, we like to sort of map out ideal ways of a product being used or like, call it a workflow before you've even designed anything and sort of probe into that with clinicians or end users.

Is this really going to work? Do we need to make more considerations? So doing as much sort of agile and all these buzzwords and everything up front before you're really committed is hugely like, that's.

That's definitely the best starting point.

Etienne Nichols: I love that you brought that up because you basically hit the nail on the head as far as the mistake I would have come to you with, because I'm just going to give you, my example.

I was like, okay, well, I have a device in mind.

Let's say my wife, just full disclosure, she's a registered nurse and she experiences issues. So, she's a critical care nurse as well. And she experiences issues, things she doesn't like, and she has ideas sometimes.

Like, Etienne, you're a mechanical engineer. Why don't you fix this problem this way? And she has an idea. And so, one of the things she would love to see is a connected IV pole that instead of beeping in the room, it beeps at the nurse's phone, because they always carry around their phones, but they don't really get a message that the IV pole is beeping. It's just the person in the bed who's annoyed. And so, I might say, okay, well, I'll just make a connected IV poll.

And so, I want to come to you and do that. But you already told me, you said, well, what we need to do is explore the problem. If I put it in my own words, we really need to understand the actual problem.

What's the problem? They're not able to determine that this person needs another dose, or maybe the IV bag is emptied out or whatever the case may be. So that's the real problem.

Not that they need to be connected. We're jumping to a solution. Is that accurate?

Morven Shearlaw: Exactly.

And to be honest with you, sometimes the original thought about what the solution is may be the end solution, but you need to go through the process and kind of trust the process a little bit to really probe into.

Okay, so this is what's happening right now, and these are the effects of why this wasted time, or people not getting medication when they need it, or like, you see someone in their bed just really annoyed, you're already in hospital; you're already not feeling that amazing.

And then really just going out and studying, like going and looking at the problem and not being sort of stuck away behind the computer designing something without really understanding what the nurses are going through, what the patients.

Is there an impact on the patients?

Is there other things it could tie in with? Are there already other ways of working or other systems that solve some of these issues? Or you could pair up with, are there any unintended things that might happen by removing the physical distance between the nurse and patient? Are the nurses. I really don't think this for a second, but just to sort of hypothesize that if they're contacted remotely, then the visits to the actual patients might drop the face-to-face contact.

And maybe that's. I really don't think that's a case that's going to happen, just like figuring out what are the risks, because again, it's part of human factors and medical devices. It's all risk based.

Etienne Nichols: That's a really good point. And that's something that I personally forget sometimes. So, my background was manufacturing and product development, and I worked with the human factors team, and I didn't always see them as risk management.

But you're right, that really is what 62366 is based on, is all about risk management. I wonder if you could touch on that a little bit more.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, absolutely. And I think this is a point where actually our background in having a slightly broader industry portfolio background really helps because the regulatory aspect about human factors from medical devices is so heavily tied into.

Sorry, somebody's phoning me.

Etienne Nichols: No, that's okay. We're all human beings here.

Morven Shearlaw: So. Yeah, because it's so heavily tied into risk management and identifying risk and basically trying to design out, where possible, that risk to harming a patient, harming a clinician,it can get sort of siloed a little bit. You get the team of engineers, and you get the team of human factors people.

And the engineers design something, and then human factors people test it, and then they might have a few design inputs to change. But sometimes it goes so far down the process before that human factor thing is really done and essentially the product is already designed.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Morven Shearlaw: The way that, when we worked in other industries, human factors was always. Sometimes it was a bit of a nice. You really had to persuade people that you needed to go out and speak to users.

And that's where we came to realization. It's really commercially important to engage with users earlier on, because if nobody wants to buy the product, once you've designed it, then you've got a bit of a problem.

So, we've always kind of viewed human factors as something that's really integral to developing a commercially successful product, and also something that is nice to use, like enjoyable to use. That's really important as well. Whereas sometimes in medical devices, it really is just so focused on the safety aspect as it should be.

But we're always trying to layer in that, making sure there is still that kind of design element that's about, this is a nice product to use, therefore it's more safe because it's nicer to use. Also making sure that you're designing with the person that's going to be purchasing it in mind, really, that commercial element.

But the risk management is so important, and because it's so heavily tied into identifying, where could they be critical? Where could something go wrong that is really going to cause harm to someone?

And that's what the summative testing is all about. And therefore, then what allows you to prove to the FDA and MHRA and UK that it is a safe product? Because with all the sort of the horror stories of things that have happened in the past, it's really such an important element, but it's really useful to remember that actually human factors is a broader thing. It's about where people meet products and things should be nice to use and enjoyable to use, and that's where human factors can actually come in and sort of help in that design process.

Etienne Nichols: It could be a competitive differentiator, too, I would think. Something may do the job, but something else is more enjoyable to use. That's a clear winner. Yeah, absolutely.

Morven Shearlaw: I mean, I think everyone uses things in their life and everyone's got the one thing that they hate picking up because it's a pain, but they've got to use it anyway.

I was actually thinking about this just earlier on. We've been working in the ophthalmic area for a little while with a number of customers and some of that equipment that's used by opticians.

You go out, you speak to opticians, and they all say, like, verbatim, they'll all say you've got a problem with. There's a thing called a slip lamp where there's like a sort of frame that you put your chin and you put your forehead against, and then the optician will come up and look into the back of your eye.

And a lot of these are constructed in a way that they've got poles that just go straight down onto a table. And opticians are like, if a female comes in with a large chest, it's very difficult. You have to basically shovel up against its larger patients and global trends of people getting larger.

Sometimes it's impossible to get them actually into a position where you can look at their eyes. So, they end up using older techniques, more basic equipment, which means that population, a certain number of the population, are getting less, they're getting less care than other people, which is not right.

But it's just kind of accepted that the equipment, it's like, oh, well. And the equipment manufacturers, it's almost like the elephant in the room that everyone kind of knows that it's not great. And some companies are starting to try and work around about it and solve those, provide solutions that are kind of more inclusive, basically.

But certainly, yeah, there are certain industries where if you just made that difference, it would be a game changer. People be suddenly like, all right, yeah, that problem that we all just work around has suddenly gone away.

Etienne Nichols: That's a really good. I love that you bring that up, because the diversity is something that we don't always think about, women's health and so forth, when it may not be something that's specific for like that.

I would not have thought of that. I've actually been in the optometrist where we talk about the old equipment. He says, yeah, I think this has been the same equipment for the last 30 years.

And sometimes maybe things don't need to change. They meet the need, but sometimes maybe we haven't seen certain populations. So that's a really good point. I'd be curious to know if you.

Well, let me back up. Most companies probably want to build a device that is somewhat human centered. Maybe that's not the focus, but they probably have that somewhere in their goals, even if it's just a nice to have even some of those companies who are focused on it. What do you consistently see them fall down on or really forget about any pitfalls.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, I think it's kind of what we touched on before. We are the same in the team. You want to get to the solutions; you want to get to the.

Okay, let's go to engineer.

Etienne Nichols: It's an engineering thing. Yeah.

Morven Shearlaw: That's what is exciting about doing design. It's like doing stuff, testing it out. And companies that even are focused on that sort of human factors or user centered development, there is a tendency to want to go as fast as possible, which is completely understandable. It's commercial organizations, projects have got budgets and projects have got timelines, and there's a desire to try and keep to those.

But I think it's jumping to solutions and then probably not testing enough with people early on. Like the example I was talking about, just screen placement, a bit of cardboard kind of simulates that you don't need to develop something that's a fully working functional prototype. There's a nervousness as well to go out to users.

Everybody knows, you know, you need feedback, but you don't necessarily want to go and get that feedback because you might be wrong. Right. So, I think that's human nature.

Etienne Nichols: Sorry, I didn't mean to interrupt. I'd be curious if you have any stories about going out and getting that feedback.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, actually there's one that comes to mind, and it was probably one of our first big medical device projects where we were absolutely excited to have got the project to do. It was reinventing a piece of imaging equipment. Basically. I can't see too much. I'll try and tell the story.

Etienne Nichols: No, I understand.

Morven Shearlaw: But basically, the customer had come with a brief. They were getting a certain amount of feedback from the field that they weren't selling because their product was too expensive. So, they wanted to make a kind of an entry level product that meant that they could hit more markets and hopefully sell more units.

So, that was fine. And luckily, they were happy for us to go out and do some sort of market investigation and talk with clinicians in the UK and the US as well, because obviously those markets are a bit different in terms of how healthcare is set up and the US being a bigger market. Anyway, so we went out and spoke to.

I actually was involved in this. There was four of us, or three of us went out and spent two or three days in a hospital talking to clinicians and nurses that were all involved in this procedure, in this sort of area of health.

And we filmed people talking. And this was a big mistake I made. I filmed someone without actually asking them. So, they were fine afterwards, but they were a bit surprised.

So, I would say, yeah, always learning on the job. This is a while ago as well. So, it's all on sort of camera phones and everything.

And basically, the clinicians absolutely ripped into the product. They just said, oh, it's terrible and it doesn't work with all my other devices. And it's big and clunky and we love the technology. The technology is great, but the thing is, I'm paying to use and.

Etienne Nichols: They.

Morven Shearlaw: Were sewing us where the patient would be and it's like, well, it doesn't affect where the patient is, and if the patient's bigger, then it's just too big. So, they gave us all this really great feedback where it's like, okay, that is starting to give some pretty clear design directions.

These are things that really, these are the reasons that people aren't buying it. It's actually not the technology and it's maybe not the price. If they were persuaded of the value, then the price would maybe start to be less of an issue. We're written fantastic, edited it together, sort of sound bites on pretty damning stuff, and then shared it with the company.

And the, the CEO basically sort of jaw hit the table because he was like, why don't we know this? This is crazy that we don't know this about our users and our market. And basically, a lot of people in the company did know it.

The sales force and the clinical training force were always getting this feedback, but they never wanted to really communicate it in that way because for whatever reason, they were nervous about seeing bad things about the product back into the sort of management.

So, it was a bit awkward for us because actually there was some slightly awkward conversations. But I mean, it was ultimately really valuable for the project because it meant that there was some clear direction and it sort of changed what the brief was, which was we need to solve these problems.

And maybe it doesn't necessarily need to be a cheap, cheap product, it could be a more expensive product. But as long as it works well for these clinicians and fits into how they want to work, because that's really important.

A lot of people that are doing these jobs are really skilled. They've been doing them for a long time. They've got very set ways of working and they're not about to relearn something just because it might give them a little bit of. It might be slightly better technology, but ultimately, they could do it a different way, they could do it the way they've done it for a certain number of years. So, it was an eye opener for us as well.

The distance between a company and their users just having that third party involved. Sometimes you get better, more in depth information because people want, you want to please people, you want to tell them what they want to hear.

If someone's asking you a question, who's from that company?

And it's one of the things about user testing; you have to really frame it. You have to be very careful about how you test with people, because ultimately people will want to tell you what they think. You want you to hear that good or bad.

Etienne Nichols: That's interesting. And this is a little bit off. Maybe it's not completely relevant, but it made me think of, just in talking with people in general, you mentioned that third party being a good go between or the one who's not.

They're able to give the unsanitized information, and you don't want to be that bearer of bad news. But on the flip side, just in dealing with people in general, I've learned that secondhand compliments are sometimes the best that you want to receive.

And what I mean by a secondhand compliment is I could tell you, hey, you look nice today, but if I hear someone else say, hey, that report they did was amazing.

And I say, hey, I heard the CEO likes your report. That means a lot more than you come for me, because I get nothing out of telling you that. So sometimes those secondhand.

But in business, we're all humans.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, absolutely. And I think it's really important to remember that, that people have egos and they want to please as well. But, yeah, absolutely. I think that just having that sort of slight barrier between two parties that are quite interlinked does help get richer information out. And then the trick, or the skill is sort of using that information and then sort of turning it into design, actually accepting it. Exactly.

Etienne Nichols: So you gave a lot of questions earlier on, and I wish there was a way for me to just kind of bullet point every one of those out because I asked, okay, let's say we have a theoretical design, and you said, well, let's go back and I would ask you this question and this question, what's the actual problem you're trying to solve?

Who's going to interact with the device and all these different things?

Maybe this is probably a question more for Charlotte, who's on the call just a minute ago, our marketing person. But that would be a fantastic maybe checklist. I don't know if there could even be a comprehensive checklist but if I wanted a human centered device, I wonder if that'd be something we could build.

Just where you ask all these questions, these are things you have to do. At least a baseline. There may be me additional on top of that, but a checklist of questions to ask. Maybe if that's something we could put together and download and put in the show notes, I think that would be fantastic. But I don't want to put you on the spot on recording.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, absolutely.

It's such a broad thing because it is about looking at the market as well and figuring out who your controllers are. Yeah, absolutely. I think that would be a really kind of useful resource because it's the kind of things that we would mentally start logging at a start of a project anyway.

These are the things we need to find out. These are the conversations we need to have. So. Yeah, absolutely. But yeah, as long as you're not asking me to detail your questionnaire right now.

Etienne Nichols: No. Yeah, maybe we could put that together. Those of you listening, I'll keep you posted on whether or not this is able to come to fruition. I don't mean to put you on the spot right now, so that's really cool.

I'm curious if you other have resources or books, and I'll give you an example. So, I didn't know a lot about HF, but a friend of mine who was in human factors recommended the design of everyday things. I think it was Don Norman, someone who originally worked at Apple.

It's been a long time since I read the book, but anyway, he talked about all the different affordances, signifiers, and it made me really appreciate human factors from a human centered design approach.

Any recommendations as far as that goes, as books or.

Morven Shearlaw: I mean, absolutely. The Don Norman one is a kind of classic starter point.

I think. Weirdly, often the books that I find the most useful, and I think I'll have to give it to you in the show notes because I. Yeah, that's fine. Name in a moment was a woman who. She was a journalist, and she lived for a year. I'm not going to say the country because I'm going to get it wrong, but she really immersed herself in the way that people were living there and just lived as it wasn't Tibet, but it was something like that.

She was like living with a nomadic tribe and really understood how they dealt with things. And then that helped her come back and talk about informing policy and things and books like that, where that is.

Basically, it's human factors plus, if you know what I mean. Really being a method actor and just basically becoming as close to the people you're working with as possible. So, yeah, I do have a couple of books that I would recommend, but I'm sorry, they're going to have to be in the show notes.

Certainly, the ones I find the most useful when you're thinking about engaging with people and talking to people are they tend to be the more kind of psychology-based information rather than the nuts and bolts of human factors. Like, how do you have natural conversations with people? There's a really good book called the Mom Test, which is actually, I'm sorry, I'm not American, so I'm saying, mom.

Etienne Nichols: No, this is great.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, that's a fantastic one. Because it's about building new products. It's about building digital products, actually. It's not medical devices at all, but it's about how to ask questions that even your mum couldn't give you the answer because your mom's always going to be nice to you, and she's always going to give you the answer she thinks she wants.

So how do you have conversations with people that will help you build better products and really get the answers to the questions that you're asking without the best answers come out of not actually saying, here, I've thought of this product.

What do you think about it? Because people will go, that's great. They're not going to say, well, actually, it's not going to fit into my daily routine because I already do this, and I do that. They're not going to think in that way.

So, you have to talk to people around about a product with that in mind, but not talking about the solution, not talking about the design of it. Just really trying to figure out as much about them and what they need.

I think that's a great one. It's really accessible, it's really easy to read, and it sort of opens your mind to, like, okay, yeah, I did ask that in a really stupid way. Of course, that person's going to say that. It's a great.

Yeah, I can build up a couple of more suggestions at the moment.

Etienne Nichols: Oh, no, that's fantastic.

Morven Shearlaw: Don Norman's definitely a classic intersection of psychology and design is really okay.

Etienne Nichols: And that book you mentioned, I know I'm getting a little off topic here, but there's a book about Robert Moses called the Power Broker. The author of that book wrote one.

I can't remember which president he talked about, but he lived in New York, and he wanted to learn about this president. So, he actually went and lived in Texas for several years so he could understand the president better as he was writing his biography.

But it just made me think of that. Just the book you were mentioning. The book, the mom test, How to Talk to customers and learn if your business is a good idea when everyone is lying to you. I love that title.

I'm going to put that on my Amazon cart right now, actually, so I'll put that in the show notes so people can find it. Very cool.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, I think potentially you've got the same issue as I have, which is like someone mentions, you're like, okay, I'll buy it. And then you've got a huge pile that you're sort of trying to get yourself through.

Etienne Nichols: One person gave me a great idea. He said, what you need to do is you put it on audio, get the audiobook and listen to it at one and a half or two times speed.

And if you think you're really getting into something, if you go through it two times, buy the actual book, and then you can mark it up. And that way I filter it that way. So, I listen to a lot of books and then I read a smaller amount of books.

Morven Shearlaw: A smaller amount. Yeah. That's probably a sensible thing. Yeah. I find there's a couple of podcasts that I have to listen at a faster pace just because the people speak so slowly.

Etienne Nichols: I know, yeah, it's a tough balance. Yeah.

Very cool. So, one other thing I wanted to ask about just with this is, what about the standard itself? When you get into usability, we talk about just focusing on the user and focusing on the problem, and I'll just throw out a statement. Someone told me early on in my career that really helped in a lot of different areas, not just with design of a product, but even your processes and things like that when you're trying to be a little bit more efficient.

And they said the heart of the problem is the seed of the solution. So really understand what the problem is you're trying to accomplish. I mean, it's what you've been talking about this whole time.

But what about the standards and including all of those things, what are some things that maybe they're getting it from a human centered perspective, but what are those companies that are focusing on that? But maybe they're still not getting that the standards are going to require anything come to mind?

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, it's a huge sort of education piece that a company needs to do internally or with the help of a sort of regulatory input is identifying all the standards that you're going to need to comply with.

And that can be difficult as well. If it's an innovation where there isn't necessarily, there isn't necessarily design standards that actually tie in closely in terms of the risk of management and the human factors.

A definite issue is people starting it too late. Like I sort of mentioned before bringing, and in fact I was talking to consultant ergonomics the other day and he said a lot of his work is summative studies where he's brought in and he's like, this is formative, you're actually still developing it and you're not close to summative or it's so designed. And the issues you have are just now inherent in the product and then it becomes, well, you make the instructions better and unfortunately the burden then becomes on instructions.

And obviously instructions are not a solution. Instructions are a necessary part of a medical device. You need IFUs. You need IFUs that are proven to be understandable. But it is a bit of a sticking plaster on design issues. And obviously like who reads IFUs?

Etienne Nichols: The last-ditch effort. Right?

Morven Shearlaw: Exactly.

So, I think probably that sort of starting it too late or assuming that it is something that is going to be a simple bolt on, on the end is definitely.

But in saying that, I think anyone that is engaged in sort of has bought into human factors requirement or like the fact that they need to focus on their users are at least in the right mindset to be aware or informed that there's a regulatory process that needs to be developed. There needs to be a design history file. You need to have the evidence and not just building that evidence to build the file using that process.

It should be happening naturally, and the regulatory side is just to kind logged, if you know what I mean, rather than sort of doing it as the tick box exercise. But it's certainly, I mean it's the thing that ergonomics, some human factors specialists moan about. It's kind of their industry bugbear about medical device companies sort of coming going can you do a summative testing? And then they're really just doing it because it's a regulatory requirement, which is the wrong way of thinking.

Quality management is about quality.

It's not just about proving that you can sell in the market because you've got a certain certification. It should be driving the quality of the product and helping you develop something that is the best it possibly can be, rather than just something you need to do.

Etienne Nichols: Absolutely.

The. I've talked to people about this before, as far as your design history file and the design controls, it's really just a formalized process of what good engineering already does.

I mean, you already should be thinking about the user needs that you've been in other industries that maybe that wasn't formalized, maybe it was, I don't know exactly, but I've worked outside the regulated environment where you still want to know what your customer is looking for.

Otherwise, you're not going to be able to sell it. And you need to know what their needs are so that you can go into those design inputs, design outputs and so forth. But this is just a formalized way, it's the best practices. And so, it should be used.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, exactly.

Etienne Nichols: Differentiator.

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah. They shouldn't be existing separately. It really is a sort of symbiotic relationship. And yet the design controls are there to help you build the evidence.

Ultimately, rather than something that should be driving the development, that development should be happening like that. Anyway.

Etienne Nichols: So, I'm going to put several things in the show notes. I'll put some links to how we can find you, links to the books you recommended. Maybe we can get that other one as well.

I'll try to find it and maybe you can send it to me. If we could do the downloadable, we'll see, we'll find out.

They're going to get on to me. You don't put people on the spot when you're recording them. But anyway, appreciate your good sport. Anything we're missing? Any other thoughts that you have, piece of advice you have for companies?

Morven Shearlaw: Yes. Well, just go out and talk to people, go out and seek feedback, because ultimately it makes better design happen, it makes better products happen. We are all human beings, so we should be thinking about us in everything we do. So, yeah, sorry, that's a little bit kind of high and mighty as an ending point.

Etienne Nichols: Well, it's true and I love how you started off. You start off that way, I think it's fair to end that way. Just remember the whole supply chain of people who are going to interact with the device.

Talk to all of those people. It's difficult and it could be intimidating, but yeah, absolutely.

Morven Shearlaw: I love finding about things that you don't know about. So naturally I think it's a great thing to do.

Etienne Nichols: I think that's a good piece of advice, is just to be curious. But I remembered a question I wanted to ask you, and that was you had mentioned how it can be intimidating to go out there and talk to those people.

And you also mentioned even the person who's reprocessing the device. But how do you recommend getting a hold of some of those people. And any tips on that aspect?

Morven Shearlaw: Yeah, so we have done all sorts of different things where you just talk to as many people in your sort of social network and just people in the company, you say, do you know anyone that is an X?

We also do use recruitment companies, which I think is important for later stages where you're bringing in truly impartial. And if you've got a really kind of niche area you're looking at.

And actually, that pool of people is quite small in the world. For example, we're doing a project within neurosurgery, so we need to speak to a certain type of neurosurgeon. So obviously those are busy people. Those are very time impressed people.

So actually, you need a third party to go out and find them for you and engage with them in a way that they are going to respond to. I am a great lover of LinkedIn and just sending people messages and going, hi, I've noticed you're. Would you mind having a really, I need an expert, and I want to talk to someone for 20 minutes.

Would you mind having a chat?

I usually word it a little bit better than that, and it can be scattergun and you might only get a few people, but definitely you have to be a little bit inventive. But then you do want to make sure that you're not bringing in too much kind of personal bias where somebody's like, it's a friend of a friend, so they don't want to upset you, and they want to give you an honest feedback. Right. And yeah, it depends if you're looking for a certain type of patient as well.

Good things are like patient support groups, if you want to speak to families of looking after family members who've got dementia or something, not necessarily talking to the patient themselves, but talking to the family members going out and just reaching out to charitable groups and organizations or people that meet for coffee every Tuesday to get some sort of community support.

Basically, just be know, fantastic advice. Yeah, I love, yeah, be inventive and don't be afraid to sort of ask the question because usually people want to help.

Etienne Nichols: Right. Yeah, that's good advice. I love that. Well, Morven, thank you so much for being on the show. I really appreciate it. Those of you been listening, you've been listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Check the show notes. We're going to try to have some good stuff in there for you. And until next time, we will see you all later.

Take care.

Thank you so much for listening. If you enjoyed this episode. Can I ask a special favor from you? Can you leave us a review on iTunes? I know most of us have never done that before, but if you're listening on the phone, look at the iTunes app. Scroll down to the bottom where it says leave a review. It's actually really easy. Same thing with computer. Just look for that leave a review button. This helps others find us, and it lets us know how we're doing. Also, I'd personally love to hear from you on LinkedIn. Reach out to me. I read and respond to every message because hearing your feedback is the only way I'm going to get better. Thanks again for listening, and we'll see you next time.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

.png)

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...