MedTech Startup Survival Guide with Steve Bell

In this episode, host Etienne Nichols sits down with seasoned MedTech entrepreneur Steve Bell to discuss the critical lessons for starting and scaling a medical device company. With over 30 years of global experience, Steve shares insights from his work with major corporations like Johnson & Johnson and his role in building Europe’s largest MedTech unicorn. He reveals how a conversation with his wife led him to develop an extensive course and a new MedTech AI tool to help founders navigate the complex and often unforgiving startup landscape.

Steve emphasizes the importance of moving beyond a great idea to build a viable business. He outlines the foundational mistakes that sink over 75% of startups, from emotional attachment to non-viable concepts to underestimating the time and financial commitment required. He introduces his “greenhouse score” system, an objective, data-driven tool designed to help founders evaluate their business idea against global competition, urging them to "kill their ideas early" if they aren't built for success.

The conversation also touches on the unique challenges facing first-time founders, including the critical decision of who should lead the company. Steve advises against a "have-a-go-hero" mentality and highlights the value of bringing in experienced leadership to avoid costly mistakes. He stresses that true success lies in being "needs-based, not product-based," focusing on solving a core problem rather than becoming overly attached to a specific solution. The episode concludes with a warning about protecting intellectual property (IP) and the costly mistake of sharing proprietary information prematurely.

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Love this episode? Leave a review on iTunes!

Have suggestions or topics you’d like to hear about? Email us at podcast@greenlight.guru.

Key Timestamps

- 00:02:13 The origin story of Steve's MedTech startup course.

- 00:04:58 The #1 reason MedTech startups fail: A good idea isn't always a good business.

- 00:08:54 The greenhouse score and MedTech AI advisor for objective business idea validation.

- 00:11:09 Why entrepreneurship is a "wide open field" and how to find a path.

- 00:12:00 The importance of "Location, Location, Location" for MedTech startups.

- 00:13:58 The MedTech Survival Guide book and life lessons learned.

- 00:17:02 Should a first-time founder be the CEO?

- 00:18:10 How to find and compensate an experienced CEO.

- 00:20:45 Why you must be needs-based, not product-based.

- 00:22:47 The difference between a business and an orphan or philanthropic project.

- 00:23:53 The risk of destroying your IP before you even get started.

Top takeaways from this episode

- Validate Your Idea Objectively: Don't rely on gut feelings. Use data-driven tools to assess your business idea's viability. If your "greenhouse score" is low, don't abandon the need—pivot the solution or fix the weaknesses.

- Stack the Deck in Your Favor: Simple, logical choices can significantly increase your odds of success. This includes selecting a strategic business location and prioritizing a strong team over a lone "have-a-go-hero" founder.

- Hire Experienced Leadership: A first-time founder should rarely be the CEO. Bringing in a seasoned professional with C-suite experience can save millions of dollars and years of development, as they bring invaluable scar tissue and a network of investors.

- Protect Your Intellectual Property: Be mindful of how you share information. Publishing abstracts or presenting data prematurely can destroy your ability to patent your invention. Treat your IP like a "billion-dollar map" and guard it accordingly.

- Focus on the "Need," Not the "Product": Your passion should be for solving a problem, not for a specific device. Your initial product idea may not be the one that succeeds, but your mission to solve the underlying clinical need should remain constant.

References:

- Steve Bell's MedTech Course: An extensive online course with over 100 videos designed to guide MedTech entrepreneurs from concept to exit.

- MedTech Advisor AI: An upcoming tool that uses an algorithm to provide an objective "greenhouse score" for MedTech business ideas.

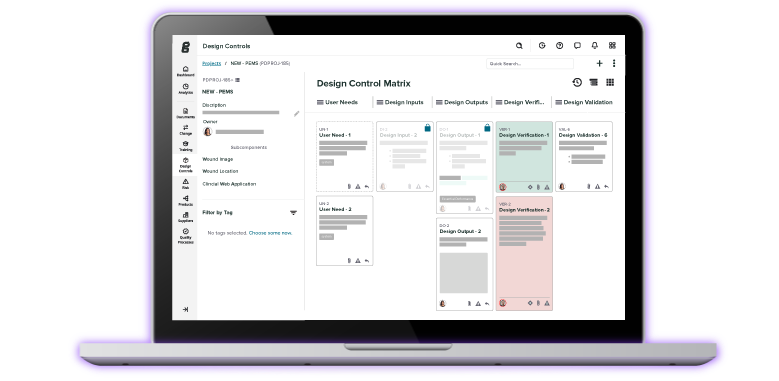

- Greenlight Guru: Provides both a QMS and an EDC solution to help medical device companies of all sizes manage their product development and quality processes.

- Etienne Nichols' LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/etienne-nichols-10705174/

MedTech 101: The Entrepreneur's Mindset

In MedTech, a startup is a new company in its early stages, often focused on a single breakthrough technology. But as Steve Bell explains, a great technical idea isn't enough; you need a great business idea. This means the company must have a clear path to profitability and market sustainability.

Think of it this way: a car enthusiast might build a highly advanced, custom race car in their garage (a great technical idea). But if it costs a fortune to build and can only compete in a small, niche racing circuit with no prize money, it's not a viable business. An entrepreneur, on the other hand, would look at a market need—say, a demand for affordable, electric delivery vehicles—and then design a vehicle to meet that need, ensuring there's a clear way to make a profit. The entrepreneur focuses on the market need first, not just the technology.

Memorable quotes from this episode

- "Every idea is good, but not every idea is a good business... some of them are just really interesting tech that's trying to look for a home." - Steve Bell

- "Most likely thing for most companies is the idea you go in with is not the idea you come out with... You need to be needs-based, not product-based." - Steve Bell

Feedback Call-to-Action:

What are your biggest challenges as a MedTech entrepreneur? Email us your questions or topic suggestions at podcast@greenlight.guru. We read every message and value your input! Your feedback helps us shape future episodes and provide the most relevant content for the MedTech community.

Sponsors

This episode is brought to you by Greenlight Guru. Launching a MedTech startup is a marathon, not a sprint, and managing your quality and clinical data shouldn't slow you down. Greenlight Guru offers a modern, intuitive QMS & EDC solution specifically for medical device professionals. Our software helps you streamline your product development, ensuring you can focus on building a successful business without getting bogged down by compliance issues. Greenlight Guru provides the tools you need to stay on track from concept to market and beyond.

Transcript

Etienne Nichols: Hey everyone. Welcome back to the Global Medical Device Podcast. My name is Etienne Nichols. I'm the host for today's episode and today I want to talk about how to start up in MedTech.

And with me today to talk about this is Steve Bell, who's a veteran MedTech entrepreneur with over 30 years of global experience scaling startups, commercializing breakthrough technologies and advising early-stage ventures.

He's helped build Europe's largest MedTech unicorn, led the global launch of the Versus Surgical Robot at CMR Surgical, and he now serves as a strategic advisor and co-founder across multiple cutting-edge initiatives from AI powered business models to next gen diagnostics.

Steve brings deep expertise in go to market strategy, funding and leadership innovation with a focus on helping MedTech teams avoid the pitfalls that sink over 75% of startups. And so, I'm really excited to have this conversation with you today.

Steve, how are you doing today?

Steve Bell: Yeah, great. Etienne, thanks very much for inviting me on. Always glad to be here. And for those that don't know, Etienne, by the way, is the French pronunciation of Steven. So yeah, we're linked.

Etienne Nichols: Absolutely nailed it. And you know, it's funny, my mom tells me I don't even say it correctly. So, I always love hearing people who, who speak the French language.

I want to say.

So, I've joined the course because I wanted to get a little bit of prep and foundation in your course because you've built out something, what is it like? Over a hundred different videos and it's very extensive and as it should be because building a medical device company is extensive.

But I'm curious if you could talk to some of the, some of the depth that you have to go into in order maybe this is even getting back into your background. Can you, can you give us a little bit of background on what you've built?

Steve Bell: Yeah. So, you know, I've spent a long time either building startups in major corporations like Johnson Johnson did many of the startups in their cardiovascians being one of them.

Gyneco was one of the other ones that we did in there and then I did multiple California startups, and I worked with some of the best startup people in the world who'd already done before me multiple startups, many that crashed and failed because as you rightly said, over 75% crash and fail.

So, I've been surrounded for the last 20 years with people who just do this on a regular basis.

And I started seeing some patterns. There was those clear patterns of those who have a much higher hit rate and those that don't.

And I been through it myself. Multiple startups crashed, a few done well on a few.

And there's some patterns that start to emerge.

And I just thought to myself, most of this is just not repeating the mistakes that everybody knows are the basic mistakes.

And if you take the life of a startup from concept on the back of a napkin all the way through to either exit or death of a company, or you should kill a company, quite often there's kind of like about a hundred steps that you go through, and in each of those steps there's just a really simple what you should do and what you shouldn't do.

And I found that those people who generally follow the what you should do and avoid the what you shouldn't do don't get in as much trouble in their startup.

So, I spent a lot of time on phone calls at night with startup entrepreneurs who were asking me these questions. And every night I would repeat the same stuff. And my wife just walked into the room one night when I put the phone down and she said,

I can't hear you say this one more time. I just can't hear you do it.

You need to just record this and put it online for somebody because I can't have you do this one more time. You've been doing this for two years, every night and you say the same things.

So that was when the. So, the impetus came that I thought, well, okay, there are these life lessons. There is a very basic sort of recipe book for success.

You can definitely take it from the 80% failure to the 50% with some very simple things.

And why don't I just stick this online so that people can just get access to it and I don't have to spend every evening repeating it. So that was the genesis of it.

And I.

It broke into a handy 100 pieces. It wasn't by choice, actually. It's actually that's how it actually worked out. But it's just right that on that journey, there's about a hundred segments of the life of a startup that you need to follow.

Etienne Nichols: I'm curious what your wife kept hearing. Are there any. I mean, because over the hundred, there have to be certain spikes that this one, you know, the top five or something like that.

Steve Bell: Yeah, yeah, there are. So, she kept hearing me say, often that's just a dumb idea.

Why you, why you think you're going to spend your next 10 years of your life and all that money on something that you know everybody knows is going to fail just because it's a pet project?

So, my number one thing that I talk about to a lot of people is, you know, every idea is good, but not every idea is a good business.

And some of them are really dumb businesses. You know, they're just really, really interesting tech that's trying to look for a home. And even if it finds a home or a clinical need that it's filling, that doesn't mean it's a good business.

And I always talk about something called the water speculum, which is speculums. Like I've been out for years and years and there's at least once or twice a year I get sent a new idea for a speculum, which is just not a business.

There's no business in that. And people are willing to spend time and money. So, my number one thing is if you're going to have an idea, make the idea worthwhile.

You're about to spend a decade of your life on it.

The second piece of that is if it's not a good business idea, why is anyone going to put money into it?

And this is not about R&D; this is not about MedTech. It's about med tech business.

And if you can't have a, you know, a really interesting business that's going to be successful, no one's going to put money into it. They'll see through it in two seconds. You know, there are smart investors out there. So, the next thing is, you know, make sure that you've got a good idea, it's a good business idea, and it's going to make money in this. You know, if I put $10 in, I get a hundred dollars out, how does that work?

And you've got to be able to articulate that.

The other thing then about that is have a big idea.

There are lots of great small orphan diseases or small orphan needs that need to be done.

But that for me is not going to be a business.

Investors are looking for the big shots. They're looking for the, for the, the big needs that affect a lot of people.

And the reason for that is just simple math, right? If you've only got a hundred patients worldwide that can ever use your device and you've got to make a hundred million investment to do it, you got to sell that at such a phenomenal high cost, you're never going to make money. So, I exaggerate on the size of it there, but that's the lens that you need to look through.

You got to look through that filter and say, okay, is this big enough to affect enough people to be a sustainable growth business with profit?

Because that's what the investors will ask.

So, if you kind of take those first three things together, it's, it's a lot around the idea.

And I, I tell people, kill your ideas very, very early.

And the reason for that is that you only have maybe four or five genuine startups in you in a lifetime because they take so long. Now it's average exit at the minute in MedTech is 12 years.

That's the average exit. Average, yeah. And you're going to raise, you need a lot of money, you know, maybe a hundred million dollars for a decent product.

10 years.

A lot of people will lose their houses; a lot of people will lose their college funds.

You better make sure that whatever you're doing is absolutely worth it, bankable. And if it hits, it's going to hit big so that you get the reward.

And that's why I generally at the beginning try and say, and I know people love their, love their children, they love their babies, and their ideas are just absolutely the best thing they've ever had.

If it isn't a good business that's investable, you gotta kill it and kill it fast because the idea is important, the team is important, but the two together is the critical piece. It has to be a good idea with a good team. And that's why she makes a good business.

Etienne Nichols: I can hear someone saying that, maybe listening to you and saying, totally agreeing with you. But here's the problem.

They're so close to this problem that they're trying to solve that they maybe they haven't zoomed out and actually been able to see that, you know, maybe this isn't actually a business viable product.

So how do you, how do you fix that, that ocular problem?

Steve Bell: That, that's, that's great. So, part of the problem is we're all human beings, right? And we, we all have emotional attachments to stuff. And what I've done in the past is I, I basically, I removed project names, I removed, and I sort of tabulated it and I did that when I was at J and J.

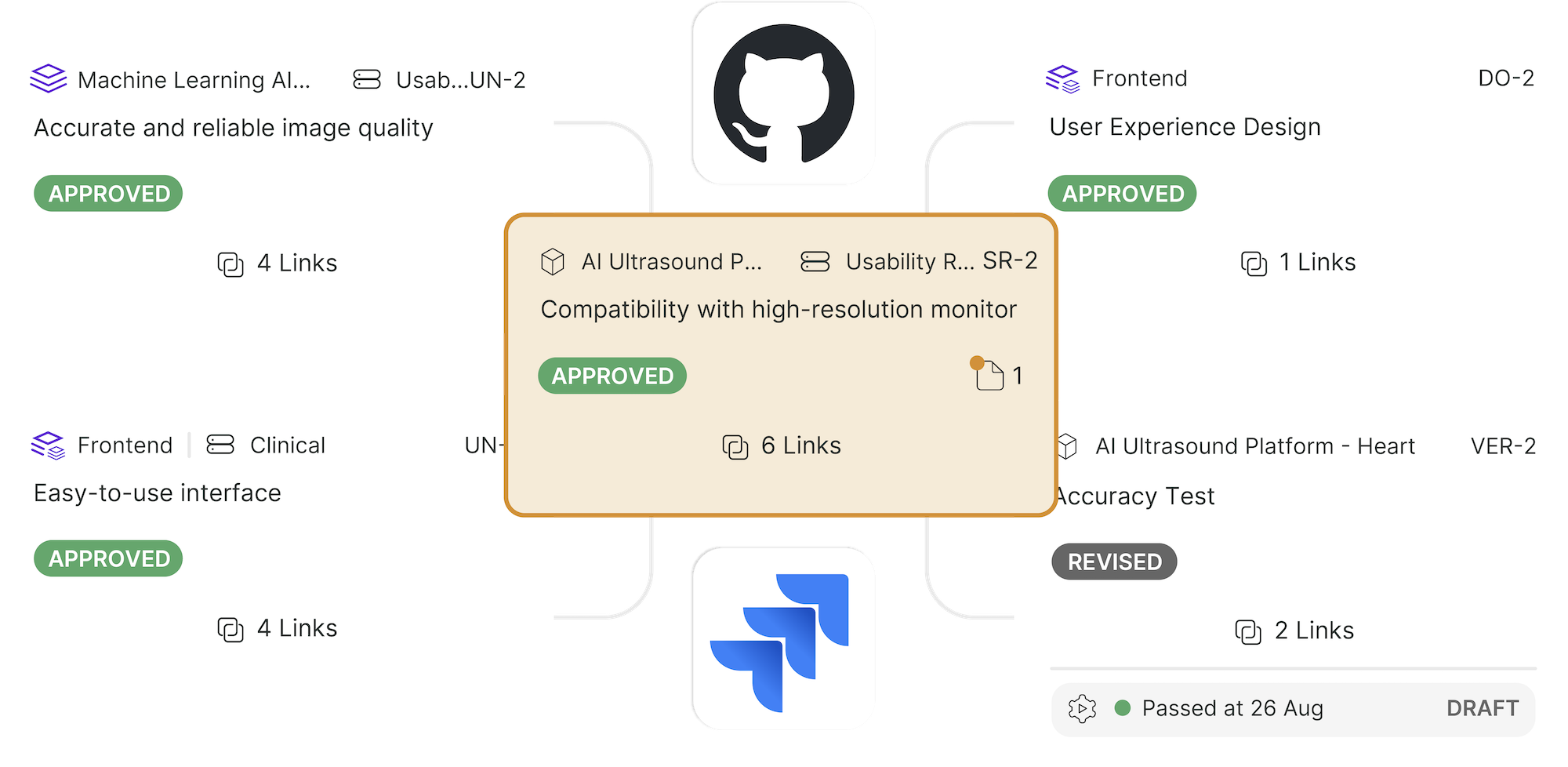

What I've done recently is I've built a score system, and you go in and you just answer 20 questions.

And I have a model that puts all those in it. It looks like it's an easy model. It's actually, it's about 330 years of information in there. It goes through a massive, weighted algorithm and it will tell you; it will give you a score, what I call the greenhouse score, which is how much chance that business has got of surviving or not. And it'll tell you the weak points. And I've just built a MedTech advisor AI that we're about to launch very soon that if you fill the score in, the AI will analyze your score and it will tell you where your weaknesses are, it'll tell you where your strengths are. So, it's not me telling you you're getting an objective score based.

And what it does is it puts you against all the other scores that we've done in the world.

So, it ranks you. And the reason why you need to do that is you can't look at your own idea in isolation.

You're competing for the same dollars as everybody else's ideas.

So, somebody else has got a better greenhouse score, which looks at all kinds of things. There’re all kinds of factors in there. It's a very complex weighted score, but that's basically how investors will also look at you.

So, if you've got a really low score down in the sort of the 50s and everybody else is up in the 120s, it's not me telling you you've got a bite at it. It's not me being emotional with you. I'm giving you a fact driven algorithm. That should give you an indication.

It doesn't mean that you can't fix the idea. You may have got it in the wrong market, you may have had the scope wrong with it, you may have got the regulatory pathway wrong.

There could be several things in there.

So, it might not be a bad idea, but it's not for another human to tell you need to have an independent partial algorithmic based score that just ranks you and therefore you can then make a decision based on that and hopefully be less emotionally attached.

Most people still stay attached even when they see they've got a score of 30 versus everyone 150 and they can see where they sit on the graph, they still say, yeah, but my idea is different.

Etienne Nichols: So that that's one of the things. Well, first of all, I think that's awesome that you built this and that's going to be really helpful to the industry because one of the things that I really believe that makes entrepreneurship difficult from just having talked to different people and interviewed over 200 medical device professionals, most of them founders, it seems that it's just not an easy path. People can go down PhD at MIT because it's a clearly defined path you go through. You take these courses, you do these things, do this research.

Whereas entrepreneurship is a wide-open field and it's not clearly defined.

Steve Bell: It's not, it's not. But there are, there are basic rules of thumb that you need to follow. So, I'll give you one of, one of the examples. One of the MOD.

One of the modules in the course is location, location, location.

You'd be amazed how many entrepreneurs, they happen to sit in some weird little town like Bad Giessen somewhere in Germany, out near Stuttgart somewhere, okay. But was far away from the epicenter of MedTech funding in the world and a small university there gives them a grant of €50,000 and they got a European grant.

So, they found their company in this weird little location.

I don't need to tell anybody that's going to be a failure who's going to come and invest in you there, right?

So, the basic thing is if you're going to, if you're going to start a business, okay, the immediate time that you first really put your company into an office, put it in somewhere where it's near a major airport, put it in somewhere where an investor from London or from the US or from, from Singapore or whatever can fly in with one flight because they're not going to take five flights, two trains, two buses and a taxi to come to your little company somewhere.

It's not happening.

So, these are basic rules of thumb. Okay. The again, it's not like it's a hard and super-fast rule, but I can tell you those who are based in the Cambridge triangle and those who are based in some weird little town in a small forgotten place in Poland, I know who's getting the investment dollars more likely doesn't mean 100% because the idea might be great. But I guarantee you most of the investors are not coming all the way out to Poland in that small place.

Simple things like that, lots of lessons like that throughout the whole MedTech thing. So, I think it is an algorithm. I think it is like a big lot, big, big complex algorithm and the more things that stack the deck in your favor, still a lot of luck involved but, but at least stack the deck in your favor.

Etienne Nichols: Absolutely. I think and it's interesting because I, I, I look at positive and negative levers and when you talk about, because you actually mentioned bring that 80% failure rate down to 50 maybe and it doesn't mean that doing these things is Going to guarantee you failure.

But by not doing them, it does guarantee you failure, I think is kind of what you're saying.

Steve Bell: Yeah, and there's, and there's just lots and lots of things, things in there that their life lessons learned. And again, I've actually got a book that's going to come out called the Medtech Survival Guide. I forgot. I think I've called it a Medtech survival guide.

And it's literally, it's going to be a hundred things that you should and should not do, you know, in a very digestible format. And this is just things that I've, you know, in 30 years I've just seen what works and what doesn't work firsthand. You know, how to raise money, how not to raise money, how to raise good money, how to raise bad money.

What does your board look like at the beginning of your company and what does your board look like at the end of your company? Two very different things. Yet I see so many startups where they have the same people on the board, which is some friends who put some money in at the beginning who know nothing about the business, who live till the end of it.

There’re all kinds of just small sort of like when you go through it and hopefully when you've gone through the course you'll sit there and say, but most of that was like really obvious because after the fact it's very obvious.

But you'd be amazed how many people go in and they try and reinvent the wheel.

Why that's madness to me and this is why I'm so passionate about this.

MedTech is one of the hardest businesses in the world. It's super regulated.

It's really difficult. Oh, got a thumbs up. It's really difficult. It's regulated. It's got so many minefields that can strip you up. Just as Medtech, J and J struggles, Medtronic struggles, Boston Scientific struggles.

Second one, startups. Startups are hard, right? Startups are really, really hard.

And now what you're trying to do is you're trying to put the two things together.

And quite often a first-time entrepreneur, first time founder, never done a startup.

Oh, it's frozen. Am I frozen or is it still working?

Etienne Nichols: Well, the video's frozen, but I still hear you.

Steve Bell: Oh, let me turn my video off and turn it back on again. For some reason it didn't like my.

Hang on.

Oh, hang on, let me turn it off and turn it on.

Etienne Nichols: Well.

Steve Bell: Oh, there we come.

Etienne Nichols: There we go.

Steve Bell: We're back.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, we're back.

Steve Bell: I Didn't. I'm not going to do the maneuver again because whenever I put my fingers together it seems to have stopped. So maybe there's some hidden thing in Apple's, Apple's algorithm. There's.

So, so, so basically you were saying yeah, yeah, yeah. And, and you know, first time founders, some of them have got MedTech experience but some haven't.

And some of them are like, you know, university grads or PhDs or engineers and, and they're like I'll have a go, you know making, making a startup in MedTech, great, love the enthusiasm. But have somebody else in the driver's seat. Have somebody who's done a startup or, and done MedTech because it's a really, really hard one to, to, to, to do a startup in.

It's, it's really quite, it's quite amazing to me how many people think I'll just have a go because I'm a surgeon.

That's the thing that amazes me the most. I know surgery. So therefore, how hard can a startup in MedTech be?

Etienne Nichols: And I actually want to talk about that. That was my next on my list.

Should a first-time founder be the CEO? And maybe if I tweak that question because I'm sure there are first time founders who are listening to this podcast and think well, I already am one, what do I do now?

You know, and, and, and what do you do if you find yourself in that situation? Are there ways to overcome it? Just all your thoughts about first time founders as CEOs.

Steve Bell: So, my, my, my rule of thumb would be never ever first-time founder, or CEO put a CEO in who's done this before or been a COO another company or a CFO another company, it doesn't really matter.

But they've been on the C suite of, and they've kind of got some scar tissue that they're going to bring along. You'll save months and millions by doing this. Right.

Etienne Nichols: I want to ask a question about that. So yeah, just because I have a specific few people who have come to me and said hey, I've invested so much money getting IP patents, etc.

I have this idea, and I really think it could work. I know other people who are, I'm a surgeon, several other surgeons, but they actually have the self-awareness to say I don't want to CEO a company.

How do I find a CEO and what do I pay a CEO? And I'm sure those are loaded questions, but any thoughts?

Steve Bell: Yeah, so I mean there are professionals out there who find CEOs for startups, you know, there's several great people and depends on whether you're in Europe or the U.S. but there's great talent management firms out there and they have on their books CEOs who are looking for, as they say, the next gig. Yeah, right. And it's not going to be cheap, but they'll take equity.

It was a great idea.

You don't pay them top dollar CEO, you know, Jane J. Money. But again, it's really funny. So, a lot of people, as the founders say, I want to do it on the cheap, don't do MedTech. Then we're looking at hundreds of millions of dollars. Right. You've got to be thinking from day one, this is an expensive venture and trying to do it on the cheap by bootstrapping it all together and you can sort of get there, but your chance of success is the lower than 50% just because of that. So go to a professional, find the right kind of CEO. And the reason for that is you'll pay the money, but they'll bring their own money to pay their own salary.

They'll go out and be able to bring in with their millions. Because people say they've done it before.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, yeah.

Steve Bell: And you know, their win is your winners, you get millions invested into your company.

Their winners, they get a nice salary and to get the options and everything.

But trying to bootstrap and do it yourself and do it as a part time gig and stuff, that's just a recipe for failure. It just can work. And I've seen the odd one work, but generally it's a recipe for failure.

Etienne Nichols: That's a really good point because a lot of times, like you said, they are surgeons who maybe are doing this. And, and I think if you just drew the illustration the other direction, who would want a pancreatic surgery on the cheek?

You're like, well, let me find the cheapest surgeon to do this. Not what we're after.

Steve Bell: Or even worse, someone who's never done a pancreatic surgery. Oh, my goodness. But, but they've developed a harmonic scalpel.

Surely. How hard, how hard can it be to do a pancreatic surgery? Can't be that hard. Right. Because I've designed a scalpel, one of the most complex things in the world, you know, the electronic scalpel.

And that's the, the, that's the flip side, opposite. For some reason surgeons and clinicians thinks it works okay that way because they're super smart people.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Steve Bell: But they don't understand it's a profession. It's an actual, you know, there's method to the madness. It's not just have a go. And that is why 85 fail, because we have this have a go hero kind of mentality of going in. The idea is good enough on its own. It's not. Most likely thing for most companies is the idea you go in with is not the idea you come out with.

It very often morphs or changes or you get through the first labs and say, oh, well, that's not going to work.

But the need is the same.

The need is the same doesn't mean that the solution is the same.

Etienne Nichols: And I've used that as an illustration before. So, I want to pressure test this with you for a minute because I've, I've used the illustration that let's say you think you're a band aid company and then suddenly band aids go out and now it's surgical glue.

If you are a wound care company, then nothing's changed for you as a company. Maybe the products change. Is that how you look at it?

Steve Bell: 100%. You need to be needs based, not product based.

The product is just a result of the need.

And there might be 15 ways to resolve the problem. The first idea you happen to have when you were in the shower that day and banged your head against the wall and said, oh, I've had a really great idea that isn't necessarily the best idea that wins in the end.

And people have to get attached to the need that they're trying to solve, and they have to get passionate, and they have to get really deeply passionate about. We're trying to fix this problem, but not the solution.

Okay? They have; they have to understand that the desperate need. The broken water pipe, okay, is the focus, not the wrench, not the screwdriver, not, you know, what, whatever is the, the, the duct tape, right?

You've got; you got to get the best solution that's going to win out for it. And honestly, how many times I've seen where startups where they go in saying, this is the idea, and three months into it they're like, that idea sucked. That was the worst thing we could have thought of. And we've got a much better idea. So, yeah, I, I think that they've got to go in with this attitude of what's the need that I'm trying to solve?

Not what's the problem I'm trying to ram down people's throat. Oh, excuse me, the product I'm trying to ram down people's throats.

Etienne Nichols: There's another thing that you mentioned earlier that made me think, because I have a question that I wanted to ask about the difference between a business and an orphan. And you mentioned something about this. Well, there's these niche places that problems that need to be solved, but it's really not a business idea.

I can hear, you know, the philanthropists and a lot of people saying, well, those problems need to be solved too. Would you, how do you look at that?

Steve Bell: And yeah, yeah, they do. And there are funds and foundations that will help with orphan ideas. There was a Kaisha Bank, Kaisha Fund in Spain was one example that had day just dedicated to orphan projects.

That would be for me, I think it's great and I think for philanthropists and stuff it's brilliant.

Etienne Nichols: Sure.

Steve Bell: But not, not if you want to make a for profit business. They are not going to be the places to do it. You, you know, some do now and again, but it's rare. I mean hyper rare.

You know, you're going to spend the next 10 years, make sure it's something that's likely to succeed and likely to turn a profit and likely to get bought or become an IPO or be a sustainable business.

What you don't want to do is go in there and say we're going to have this, you know, charity business forever.

Fine, if you want to do that. But that's not what I talk about. I, I don't believe that. That's my strength there. My strength is for profit businesses and how to get someone to hand over $50 million to you so that they can make $500 million back.

That's, that's what MedTech business is mainly about.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

You mentioned something when we first started talking about this, about how many people destroy their business before they even get started. Whether that's the IP or the moat through academic research and just, just publishing papers.

What are, what are your thoughts about that and what do you mean by that?

Steve Bell: Yeah. So, you know, at the end of the day, if you can't defend your idea legally or from secrets or whatever because people mistake IP intellectual property with patents, they mist. It's patents are part of the intellectual property.

You know, Coca Cola doesn't have a patent on the recipe. It's a secret recipe.

You know, KFC doesn't have a patent on spices, but the blend is important. So, there's a lot of secret sources that go into MedTech or businesses, especially in software and AI algorithms. There's tons of secret sauce that go in there and what often happens is to be either patents or secret sauce.

Or whatever. You, you have a lot of academics who get very excited about their idea. They just come up with this brilliant idea that they're going to fix this big problem.

And they decide one of the best things that they can do is to go and present it as an abstract at the next big congress. And they stand there, and they give away all the secret sourcing at public space.

Once you've done that, you can't patent it anymore. You've now you, you now you've given away your rights to patent it. If it's got a secret source and you put up there, you know, we do these things in this order.

There are tons of people sat there with their iPhone in the camera, just either recording you or taking screenshots of your screen and saying, well, that's easy enough. That was the thing that was holding us back.

Thank you.

That happens all the time. And yeah, you'd be amazed at how many times, you know, somebody says to me, you had this amazing idea, and amazingly, they saw the big company came out with it two years later while I was still working on it, and I said, you didn't present it, did you? And he said, yeah, I did, yeah, presented it. And I'm like, well, then you just basically gave it to them.

So, yeah, definitely. Secrets of secrets. There's a whole video on my course just about, you know, keep it as a secret because you would be amazed how many people just give this stuff away.

And I liken it to this, and I think I say it in the video, which is, if your idea is a billion dollar idea, okay, would you go to a congress with a map of your house and show where the billion dollars is sitting and tell people how they can get over your alarm, how they can disable your security features and just walk in and grab the billion dollars?

Would you do that in a public forum?

And if not, then why would you do it for your billion-dollar idea?

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, absolutely not. That's. And that was actually the thing that, I think that's a good illustration because using that illustration, you can kind of apply it to your company and understand how you.

What should be secret. But that was, I guess the question in my mind is how do you determine what should be secret and what should be fed out there as kind of teaser or whatever?

Or is there ever a situation where that makes sense?

Steve Bell: I, I think so when you're trying to get a little bit of buzz going. Well, first of all, make sure what you can patent is patented, even if it's just a provisional patent in the us.

I mean, it costs you like nothing to throw down some provisionals and it gives you a stick in the sand and the clock starts ticking. You've got 12 months into file your formals.

I think what you've got to decide is, why am I telling people this?

So, if it's just to have bragging rights to my friends, you know, in the next hospital down, that's just stupidity.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, right.

Steve Bell: That's just. That's just pure vanity. And you shouldn't be doing startups in the first place, because if it's about your own vanity, you're doing it for the wrong reasons.

So, the question would be, why am I telling people something? Well, I certainly don't want the competitors to know.

Right. Or people who potentially could make a competing product if they see it's a great idea.

If I'm going to investors, I'm trying to tease the investors. Well, there's methods and ways to do that.

Etienne Nichols: Right.

Steve Bell: Very few investors actually sign an NDA. Believe it or not, VCs, very few sign an NDA. But your early investors will. Your friends, family and fools will Definitely sign an NDA.

Get them under an NDA.

Still, in 35 years, not seen anyone sued for an NDA that's been breached, by the way. I've never personally seen it.

Not for a startup. Big companies. Yeah.

But I think what you've got to do is you've got to look at every piece of information you're putting out there, asking, why am I saying this? Do I need to say this?

And that's the filter that I would use. And again, you show more and more as people go deeper and deeper into agreeing to put money into you or to be in a partner with you.

But you, you definitely don't want to give away anything in public.

You want to be very judicious of who you tell.

You want to do your homework on investors.

So, for example, let's say you're building an ophthalmology robot, and an investor says, oh, I'd love to come and see your deck, and I'd love to see this.

And if you don't even go to their website and see that they have a competing ophthalmology robot in their portfolio already today, that's just blatant stupidity.

You've not done your diligence as much. They're doing diligence. You do your diligence. Is this an investor? Do they have contacts? Look on their LinkedIn page.

Well, they've got loads of ophthalmic companies. They got look, okay, you know, should we be showing them everything on our ophthalmic robot today? Is that the right thing for us to do today or is this just information gathering?

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that's a good point. And, and maybe that's a good segue into how to get money at different stages. I'd like to talk because I know you have in your course different, different talks about series A versus Series B versus series C and D.

I assume those are all, you know, having not taken those sections yet, I assume those are all very different.

And can we talk about the differences and, and the pros and cons and what you should be doing for each.

Steve Bell: Yeah, so, so early, early on, I mean, it's very hard to get a VC interested when you've got a napkin sketch. You know that that's not when they're investing.

Let me talk, let me talk very brief, just very briefly, about the, the way that the world of investment has changed since the early 2000 or the 1990s.

So back in sort of like the 1990s, you could walk up and down Sandhill Road in California to all the different VCs and go in with a napkin and some of them would actually think, oh, that's great, I'll put some money down.

Very early on then there was a crash in 2007, 2008. There was a lot of drawback of people putting money in. There was a lot of bubbles have been burst.

So, a lot of the venture in venture capital actually retracted a little bit.

And what I found now is that if you're looking in 2025, a lot of the VC, a lot of VCs, not all of them, but a lot of the VCs are much wanting later stage. And there's many reasons for that. One is to do with the length of cycle of funds.

So, in the 1990s, you could literally sell a napkin sketch sometimes and actually exit. You could get some basic patents and exit. You could, you know, your IP could be exited.

And the average back in 1990 for a startup was less than five years from when you did a MedTech startup to when it went out. The average was actually quite fast.

Roll Forward today is 12 years. Well, that's almost three cycles of a lot of VC funds. So of course, they're going to be much more cautious of when they put the money in, how many rounds will they have to go through, how much follow-on cash will they have to have, how much dilution will they get.

So, everyone immediately thinks startup VC, that's not the only way there are angel investors for the early seeds. So, these are people, high net worth individuals, family offices, they've got lots of money and they're looking for fairly high risk.

They're not super, super technical. They won't do as much diligence or due diligence as most of the more seasoned large firm investors.

They're more likely to have a punt and you've got your three Fs. They got friends, family and fools, you know, and yourself. You should be putting your own money in. I do say strongly, if you're not willing to put your own money into your own idea, why should somebody else put money in? Means you don't believe in it.

So, I think early on, in the early seed, pre seed stages, there's grants, there's government grants, there's non-dilutive grants, there's all kinds of money you don't have to pay back.

Go and dig as many of them as you can.

If you're in an institution like a university, I'm sure they've got some funds and grants.

There's little incubators and there's all kinds of money around and that can get you going, that can give you that seed capital to see whether your idea is going to go anywhere.

And then as you're going to get towards more of what would be defined something like a Series A. Okay, so this is where you send to get the first professional investors coming in who are looking at doing this.

You're going to go out to again some high-net-worth family offices. And some of these family offices will put 10, 20 million in. So, they're not like they're going to put in 100,000 like a friend next door.

But some of these offices will put good checks in. The strategics sometimes will put money in at that point. So, the big companies will have a fund like a J&J DC Fund, Development Corporation fund or Intuitive Ventures fund or several of the companies have investor funds, and they like to get in nice and early and make sure they are checking what's coming down the pipe.

And then you go to the VCs and there'll be different small VCs, large VCs, different funds.

And then as you go through the different funding you go to bigger VCs and then you go out to different money markets. So, there'll be private equities, there'll be large cap funds that will be putting money in.

You know, things like Softbank, they, they'll put a lot of money in things like Ali Bridge, China, some so some big funds will start putting money in so, and start small, start on the seed, close and family.

More professional investors going to the big investors as you go forwards.

And one of the things that I do say is that in the very, very early rounds, you don't really need a broker or a bank.

Once you start raising professional money, my biggest advice to people is get a bank or get a, get a proper investment advisor. Who's going to do that? They're going to cost you 6 to 8% of the raise, worth every single penny.

It's an interesting thing, you know, and it's a thing that I do want to say at this point.

The startup is trying to be a startup and build product. You're not an investment firm trying to raise money.

Sounds weird, I know that, but how much effort do you want your C suite raising money and how much of the CEO's time do you want? Literally just raising money, which is the majority of their job, by the way.

But how much of the rest of your team do you want raising money? Or do you want your CEO to have a professional investment advisor next to them who has all the contacts, can pick up the phone to a lot of people, knows exactly what your investment would suit for that fund?

I advise people very strongly that once you start getting to professional rounds, have a professional raise the money with you. A or A for you.

Etienne Nichols: Okay, interesting. And so, before we get to that point, before the CEOs raising additional rounds and so on early on with that angel investor round, are there suggestions you have when it comes to the cap table and how to manage that, that that are more beneficial later on?

Steve Bell: Yeah, yeah. So, one thing that really turns off sort of later stage investors is horrible messy cap tables that need to be cleaned up.

There's two or three things that can happen in a cap table. One is that you've got a very fragmented cap table that's just all over the place and at different rates and rounds and you've raised money at different ways and different costs, and it's not been done in a very professional way.

That becomes a very messy cap table. Try and avoid that early on. You know, get some advice from somebody in the finance world, even if it's just on how to structure your cap table, how to make your share allocation.

And then the other thing that you see often is that if you've got one or two founders, they have this weird thing of trying to cling onto all the equity, like too much equity, and they cling on to too much of it too early on and that'll work with friends and family, but that'll bite you later on.

That will bite you later on.

It doesn't look professional; it becomes a bit of a problem. And a founder who wants to retain 80% of the share of the company and only wants to give a VC 2%, they're dreaming, right? So get your cap table, especially in the first early rounds, the, the pre. Seed, the seed money.

Try and have a financial expert help you to structure those cap tables in the right way and take the right investments. You know, anybody with a check isn't necessarily a good investor.

You, you really want to have a couple of things in those early investment checks.

One is you want some industry knowledge. If you can, if you can find, you know, if it's a surgical product, other surgeons at least will understand it a bit better. So that when you have those discussions with them a bit later on, when it gets a bit feisty later on, they can understand at least the space that they're in. If it's some auntie who you know has a cake shop in, in New York or whatever, they're not often the best. Even though they'll give you 30,000, $50,000 in investment seed money, they're not always the best.

Saying that though at CMR Surgical, one of the best investors we had was an author. She actually kept the company alive in the very early days, was a local author.

So, it can work. I'm not saying absolutely no. But if you get to pick and choose your fight, make sure that you try and take some financial investors, people who've got financial links to bigger funds, so they're high net worth individuals who do they have a Rolodex and a network out to do they have it onto follow on seed capital or more capital to do bridging rounds.

Try and find some professionals who've been MedTech. Try and find some professionals who are in this space. So, if you're for example a dental company, have a couple of dentists who are putting some money in because they'll be able to get you free.

Good advice.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Steve Bell: You know, these are all the small tricks that you do early on. But don't let the cap table become 100 people giving you $10 checks. You know, that's not the way to do it.

You want, you want to set yourself a minimum amount that people come in on and structure that early rounds. You know, let's say you want half a million, you probably want 5, 6 investors coming in on a half million round max, because otherwise it becomes A mess.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. That makes sense when it comes. So, if we were to kind of move on a little bit from the funding, because there are a couple other things I wanted to ask you about.

So, one of the things that you say is stay startup as long as possible. I'm curious what. Yeah. What that means.

And I will. Maybe we'll start there.

Steve Bell: Yeah. So, there's several things that can happen and I've been part of this when it's happened as well. So, the reason that startups can actually win in spaces is because they're startups and they're agile and they can pivot very, very fast.

And pivoting happens all the time.

Right.

So, you've got to be able to be able to pivot fast. You've got to be able to do stuff on a shoestring fast, nimble.

What tends to happen is some of the investors say you need, you need someone from one of the big companies to come in.

Your C suite needs a seasoned pro and that's fine as long as they're a startup season pro.

You take somebody out of one of the big companies who's never been in a startup, the first thing they do is let's write some new SOPs.

Let's make sure that we get an expense system in and let's make sure we get this system in and let's hire some assistance for me because I'm obviously not going to book my own travel and let's get on the AMEX travel program and let's.

And what happens is, I think it was one of my colleagues at one of the last companies that said you get this thing where you just end up in sludge and you slow the startup down.

You don't have brand, you don't have size, you don't have the money, you don't have this. What you have is agility, smallness, nimbleness, and ability to flex and pitch. Very flex and pivot very, very fast.

If you throw that one advantage away, you're not going to survive.

And the way you do that is to try and stay as a startup as long as possible with the way that you hire the people that you hire.

You know, does it need an SOP or does it just need a bit of common sense and two lines in an email?

Stop having meetings for meetings sake. Once you start getting to 10 people in a room four times a week, that's no longer a startup.

That's, I want to be a big company.

So, I really say to people, the longer that you can stay as A startup, the longer you can avoid having an HR person, the longer that you can just keep that agility small where everyone's saying I'm working 130% of my time, but the CEO can literally in the morning have talked to everybody individually.

I think the longer you can stay at that, the higher the chances of success, the less chance you start getting into the spending like drunken sailors and burning through your money.

And I, and you know, we can talk a little bit about burn in a minute. But all these things, time, resources, people, energy, these, the resources that you've got to keep in the startup frame because that's your differentiator as a startup. That's the thing that makes you be able to do this faster, better, quicker, more.

Okay, we're back.

Etienne Nichols: So.

Well, you mentioned two things there. You mentioned the hiring people, you know, maybe from the larger company and you also mentioned as long as you can keep an HR, as long as you can avoid HR.

Talk to me a little bit about hiring and just your, your, your thought process about that. How do you find the right people?

Steve Bell: Yeah, hire people that you know, respect and can work with. So, so one of the things I talk a lot about in startups is you're going to spend more time with them than your family.

Right. So, you better like them, they better have the same mindset. And I talk a lot about creating a cult.

I think a startup is a cult, not in a negative sense, but it's, it's got that cult like thing is a devotion to an ideal where you're all like-minded and you all just doing what you do for the cause.

Okay, so a startup really is, should be like a cult.

So, you want like-minded people with you, especially in the early stage of a startup. And the best way you can hire is either to go to people you've done a startup with before.

If you've not done a startup before.

Personal recommendations do not go out and go through, you know, putting adverts out there that everybody can answer to.

It has to be hire people that you trust, and you get the trust either through knowing them already and seeing what they've done. You know, but reading people's CVS and stuff, I mean CVS should just be binned into the fantasy world.

Etienne Nichols: It's just, especially with AI now.

Steve Bell: Yeah, of course, you know, everyone can have a great resume, right? That reads brilliant and the hiring of it needs to be done by one person who, you know, you can't have these massive committees in the early days if you've got a Team of five people, you know, very quick, nimble.

If three of you need to sit in the room, you bring them in one interview and you decide there, and then we're taking you. Or not. Okay. If you've got to debate and deliberate, you're already no longer a startup.

You're done. You're already getting into the big company mindset and mentality, which is, let's do this by committee. Let's do some psychological testing, let's do the psychometric testing. Let's set them through a red, green, blue test.

You know, all that kind of. Kind of stuff that just. That's not what startups are about.

Etienne Nichols: So really what you're talking to, I mean, we're talking about hiring, but really what I'm hearing is more decision making in general has to be agile and nipple.

Steve Bell: Oh, absolutely. You know, you have to be able to make the decision without going through committee.

Because if you're a startup that's burning, let's say you're burning $10,000 a day and you say, I want to make a decision, and somebody says, well, can you do me a favor? Put something on my schedule for three days from now and we'll have a talk about it says three days.

There's your $30,000.

Just $30,000 are burned while you're making a decision.

You have to get into this burn, baby, burn mentality.

Everything is burn.

Every second of everyday counts. Every decision that you delay kills you because it eats your money.

It doesn't mean you always make the right decisions but make a decision and don't have it by committee.

Make it with the best person in the room with the best knowledge, makes the call and you'll get it wrong. But that's okay because you've taken action and you're wiser because you'll have learned from it.

So again, I can't stress enough, be it hiring or deciding what coffee machine you're going to have in there or whatever it is, right?

Your office space, you decide. You're the ones that's charged with doing it. Do it, come back. We all live with it.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. Sometimes I think people probably use too much of their leadership capital on, like you said, the coffee. The coffee. You want to weigh in on that? Who cares? Yeah, that makes sense.

Steve Bell: Yeah, yeah, yeah. And you'll get it wrong, right? You know, most decisions are done wrong, but then you'll adapt it and make it work because you're smart people, so don't get hung up on that. And definitely what you don't want to do is be outsourcing to an HR person. Now there's agencies out there that can help you, right?

So, if you've got somebody who you, you got a position, you just don't know anybody. You don't have a CTO. Right.

Go and find an agency that is absolutely known for finding the best startup people. You know, I, I work a lot with people like Joe Mullings, you know, Joe Mullings's group.

They'll find you a CTO and they'll find you the best CTO and they won't throw you a set of garbage. It's as good as having a friend recommend it because their reputation lives and dies on it.

So, you know, use one of them. But don't have an internal HR person who's going to do the hiring for you and then schedules you to have the interview after they've seen them.

What is going on with that with startups? You know, you should, you should not have an HR person until the last, last minute. You can take HR advice on contracts, on hiring, on legal things, setting up, you know, share schemes and all this kind of stuff.

Get advice, but don't hire an HR person.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Steve Bell: And they don't do it. You take the decision, you do it. But you take some advice from an external HR consultant or, or agency.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, makes sense.

So, we talked a lot about some of the, the top five things that, or whatever, the, the top things that stood out. I use that illustration when your wife walked in the room, said, I'm tired of hearing all this.

What are some things that are really subtle that maybe they don't come up until you really get deep? Is there anything that's just really, you have to dig deep to really get to this. But really something probably everybody needs to hear.

Steve Bell: Yeah. So, it comes up and it shows up as something deep. But it's actually there from day one. But you just didn't look at it because it wasn't the time.

So, it's friction between, it's the wrong kind of friction between the leadership team.

So, if there's four or five of you and you're all excited and the idea is great and everything's good, you're all looking through rose tinted glasses. So, you can ignore the fact that this person does that, you know, he's a bit, okay, you know, Johnny's a bit demanding sometimes when you know that's okay, fine, it's all working out.

When you're digging deep, you're getting deep into it and there's a crisis because there's always crisis and stuff. It's literally lurching from crisis to crisis in a startup.

Those small niggles that you kind of rode over at the beginning, if you don't either address them, nail them or say that person can't work with us early on, when you come to the crunch time, that's when your leadership is going to just get into absolute, you know, head smashing together.

You're not going to make decisions, people are going to be back biting, fighting, political.

They will be amplified massively in the moment of crisis.

If they're there at the moment of joy and, you know, champagne at the beginning and the, the, you know, everyone's in the love fest at the beginning and you still see it. I guarantee you when that gets amplified through the we're in a crisis and we're running out of money and you didn't do this and we didn't, those things will be amplified so big. So, you've got to watch for those early on and as a group, you've got to address them and you got to say, if we're going to work together, that has to end now.

And don't be scared. It was said by, I forget who said it, but they said cut the cancer out of the culture very early on.

So, if you see somebody who is a narcissist, okay. And a lot of people who found companies, they're narcissists. It doesn't matter if they're the founder.

The company is what counts, not the founder. This is not the founder's project.

This is a company that is a standalone entity and people forget that. And you have to remove those toxic elements very early on. And that's why you need a very strong board from day one.

And you need people on the board who'll say, we will not tolerate this early on because it's fine, you can live with the beginning, but three years down the road, it will destroy your company.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Steve Bell: So that's one of the big things that I, I see that when you get into the weeds, really, really comes up and destroys companies.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

This has been a really fun conversation and I might want to, I don't know if you'd be open to it, extending it at some point. But if there was one takeaway that you could, if you were sitting in front of a founder and you had to give them one piece of advice, what would that be?

Steve Bell: I think be honest about the need and the idea and if it's the wrong need or idea, kill it immediately. Don't hang onto it because 10 years from today you'll wish you'd killed it on that day.

And doesn't matter how good you think you are, because everyone's good, right? Everyone's brilliant, everyone's amazing. And of course it'll be different for me. I understand it's not quite right, but I'll make it right.

I understand it's not quite there, but I'll make it the great business because I'm so powerful, great and amazing that it'll happen.

Not true.

Not true.

The truth is that if the idea is bad at the beginning, it will be bad 10 years from now. And it won't be you that kills it. It will be your customers, and it will be the market that will kill it.

But don't have spent five, 10 years of your life to wait to get told by the market and the customer.

That was a bad idea. Why did you even think of that?

Be honest, rigorous, early and go to people who are not sycophants and say what do you think of that idea? And if they say that's a really bad idea, listen.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, I think that's good advice.

Well, Steve, really appreciate this and I'll just direct people to your website. How to startup in MedTech.com if there's. Do you have any other ways that people can get a hold of you or preferences?

Steve Bell: Yeah, so they can get me on LinkedIn. So, Steve G. Bell. Steve G. Bell on LinkedIn. Just join me on LinkedIn, follow me, send me a message on there and I can either be in touch or send you to the website or help you with funding through, through putting you in touch with people that are very, very good at finding with funding. I have a lot of resources on my website as well for people who can help you with funding. Experts, licensed funding professionals.

Because funding is one of the hardest things at the beginning that people have and yeah, just contact me, reach out and I'll try and help all I can.

Etienne Nichols: Fantastic. Well, we'll put all those links in the show notes so people can find them and I'm looking forward to your book coming out as well. I'd love to revisit that when that.

Steve Bell: Happens, but yeah, yeah, 50% through of the final, the final edit and I keep getting sidetracked so I will get out. It'll be, it'll be out before the end of the year, I promise.

Etienne Nichols: That's kind of like a startup in and of itself. I'm sure that's awesome. Really excited about that. Well, thanks so much, Steve. I'll let you get back to it. And those who've been listening, thank you so much.

We look forward to seeing you next time. Everybody. Everybody take care.

Thanks for tuning in to the Global Medical Device Podcast. If you found value in today's conversation, please take a moment to rate, review and subscribe on your favorite podcast platform.

If you've got thoughts or questions, we'd love to hear from you. Email us at podcast@greenlight.guru, stay connected for more insights into the future of MedTech innovation. And if you're ready to take your product development to the next level, visit us at www.greenlight.guru. until next time, keep innovating and improving the quality of life.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

.png)

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...