Andragogy in MedTech: Why Adult Learning Principles Beat Traditional Training

This episode of the Global Medical Device Podcast, hosted by Etienne Nichols with guest Shannon Decker, CEO of VBC1 and an expert in healthcare transformation, dives deep into the science of how adults learn, contrasting pedagogy (child-centered learning) with andragogy (adult-centered learning). The discussion reveals why traditional training methods, like handing new hires 40 SOPs to read, are often ineffective for experienced professionals in the MedTech industry.

Shannon explains the core principles of andragogy: adults are self-directed, problem-centered, and bring a vast reservoir of experience to the table (schema theory). They are less motivated by sequential, externally guided learning and more by what is relevant, timely, and what is in it for them. This self-directed approach means successful training in MedTech requires catering to intrinsic motivation and providing tactile, real-world practice rather than just videos or documentation.

The conversation pivots to practical applications across the medical device lifecycle. Shannon shares compelling examples, like improving physician adoption of a medical device by shifting the focus from extrinsic financial rewards and regulatory compliance to the intrinsic motivation of improving patient health outcomes. By making users part of the development process and using performance feedback to tap into a professional's competitive spirit, organizations can achieve significantly higher engagement and successful adoption of new technologies.

Watch the Video:

Listen now:

Love this episode? Leave a review on iTunes!

Have suggestions or topics you’d like to hear about? Email us at podcast@greenlight.guru.

Key timestamps

- [03:20] What is Andragogy? How adults learn differently than children.

- [04:45] The role of schema theory and existing experience in adult learning.

- [05:40] Why the traditional "drop 40 SOPs" on a new hire’s desk fails adults.

- [07:15] Case Study: The challenge of low medical device adoption and the missing education piece.

- [08:50] The power of tactile practice and addressing user confidence (e.g., misusing the device).

- [11:00] Contrasting Andragogy (self-directed) vs. Pedagogy (directed/sequential).

- [14:10] Applying adult learning to device development: solving the user's problem.

- [16:45] How to boost adoption: Intrinsic motivation and making users part of the process.

- [18:20] The key physician motivator: Desire to help people over money or administrative requirements.

- [21:10] Behavior science: Focusing on influential champions and mid/top performers for diffusion.

- [22:45] The "Gold Star" effect: Using competitive spirit and relevant KPIs for motivation.

Top takeaways from this episode

- Stop Relying on Documentation for Training: Adult learners need tactile input and practice. Replace or supplement large volumes of SOP reading with project team involvement, practical exercises, and hands-on use to build confidence and retention.

- Focus on the "What's In It For Me" (WIIFM): When designing a medical device or a training program, identify the user’s intrinsic motivations. For clinicians, this is often the desire to improve patient outcomes—lead with this message rather than revenue or regulatory burden.

- Build Champions, Not Just Compliance: Instead of solely focusing energy on low performers or the loudest voices, identify respected, influential leaders (champions) to pilot and advocate for new technology. Their positive experience drives the Law of Respect and encourages wider adoption.

- Use Performance Data as a Motivator: Feedback and benchmarking can tap into a professional’s competitive spirit. Monitor device usage and provide timely, relevant feedback (the "Gold Star" effect) using KPIs that matter to their professional values, not just revenue goals.

- Make Users Part of the Process: Involve clinicians and end-users in the development cycle early on. Actively listening to their challenges and integrating their feedback ensures the final product is designed to solve their problems and fits seamlessly into their existing workflow.

References:

- Dr. Shannon Decker's LinkedIn

- Etienne Nichols' LinkedIn: Connect with Etienne

- Schema Theory: Discussed as the framework for how adults integrate new information with their existing base of knowledge and experience.

MedTech 101 Section:Pedagogyvs. Andragogy

Pedagogy and Andragogy are two core concepts in education theory that explain how different groups of people learn.

- Pedagogy (Child Learning): This is the traditional model where the teacher is in charge. Learning is directed, sequential, and structured by an authority figure (e.g., a child must learn A before they learn B). The child relies on the teacher for direction and motivation.

- Andragogy (Adult Learning): This model recognizes that adults are fundamentally different learners. Adult learning is self-directed, problem-centered, and motivated by relevance. Adults must understand why they need to know something and how it immediately applies to their lives or work. They also leverage their deep existing experience base (their schema) to evaluate new information.

Why it matters in MedTech: In a fast-paced field like medical devices, requiring an engineer to passively read 40 procedural documents (a pedagogical approach) is inefficient. Using an andragogical approach—by giving the engineer a project, showing them how the procedure solves a real-world problem, and having them practice the task—results in faster adoption, greater compliance, and better performance.

Memorable quotes from this episode

"The way we come to learning with adults is different... The best way that they learn is coming up with things that are relevant to them, things that are timely, things that they need. They want to be interested." - Shannon Decker

"I don't talk about the money that they're going to make... What I talk to them about is by paying attention and doing these screening exams, you're going to have an impact on the overall health of your patient." - Shannon Decker

Feedback Call-to-Action

We want to hear from you! Do you use andragogy principles in your training? Have a question about leveraging intrinsic motivation in your team?

Send your feedback, episode reviews, or topic suggestions directly to the Podcast Producer: podcast@greenlight.guru. We read every email and your input helps shape the future of the Global Medical Device Podcast.

Sponsors

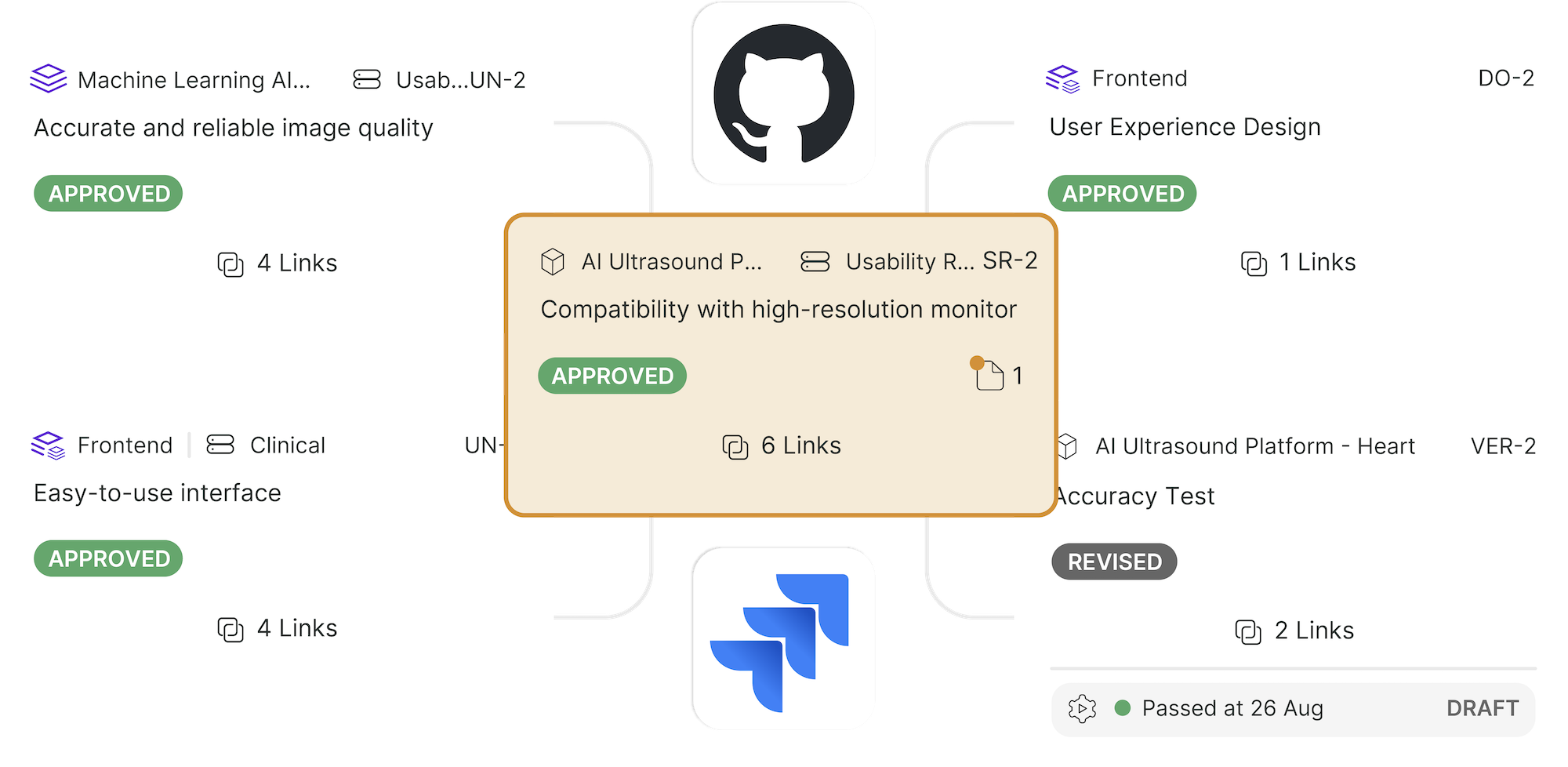

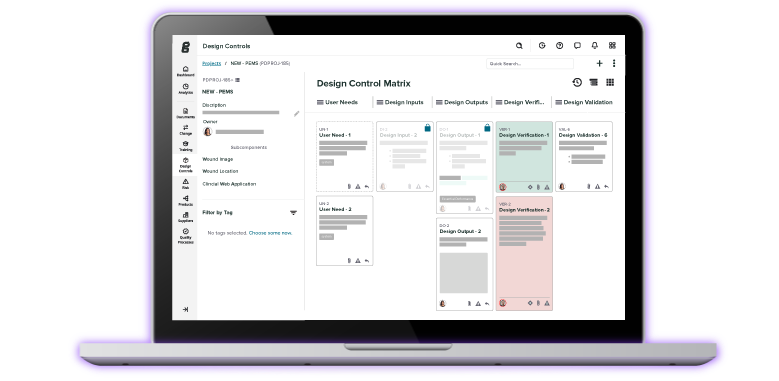

This episode is brought to you by Greenlight Guru, the only MedTech-specific platform with both a next-generation QMS and an integrated Electronic Data Capture (EDC) solution.

In an industry where successful training and adoption rely on integrating quality with practical use, Greenlight Guru helps you eliminate disconnected, clunky systems. By integrating your quality processes (QMS) with your clinical data capture (EDC), you ensure your teams are operating on the same source of truth, making it easier for adult learners—from R&D to clinical investigators—to understand and adopt your technology. Get the purpose-built platform that helps you design and build higher quality devices faster. Learn more at greenlight.guru.

Transcript

Etienne Nichols: Welcome back to the Global Medical Device Podcast. My name is Etienne Nichols. I'll be the host for today's episode. With me today to talk about something.

Well, most of. Let me start this way. Most of us think teaching is teaching, but it's apparently not.

And the way you teach children, which is the way I think a lot of us approach the world, is apparently different from how adults learn. So today we want to break down pedagogy versus andragogy, why traditional teaching models fail adults and how understanding adult learning changes everything.

So, if you train, lead or coach adults, which I think most of us in the quality world, the product development world, you are likely leading someone in some way.

This episode, our goal will be to shift the way you think about learning.

With me to talk about this subject, if I were to break it down as a pedagogy versus andragogy. With us today is Shannon Decker. She leads healthcare transformation and as CEO of Healthcare Clinical Performance Operations at VBC One, she blends deep clinical insights with scalable operations to help medical groups, health plans and providers improve the outcomes and grow revenue.

Her Goldilocks approach delivers just the right support.

And with 20 plus years in healthcare, Shannon has led rich risk adjustments, quality performance and clinical operations at Optum, Brown & Toland Physicians and HealthNet, recovering millions in lost revenue, launching telehealth programs and redefining physician engagement.

I know she's an education educator at heart. She chairs doctoral research and shapes the gen the next generation of leaders. So, thanks for being with us today.

How are you doing and did I leave anything out or misspeak there?

Dr. Shannon Decker: I'm going to copy that intro because that was like the nicest biography I think I've ever had. So, thank you so much. I don't think you left anything out and really thank you.

Etienne Nichols: Well, when we were talking a little bit, just exploring different, different topics and you mentioned this andragogy, that's a word I had never heard before.

So, I would love it if you explain a little bit about how adults learn differently from kids and what that even is.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Yeah, sure.

And glad to share it.

I actually am a professor as well and work in adult education in the social and behavioral sciences.

And, and it was a concept that came out in the 70s and it was the recognition that adults learn differently and a lot of us when we think about teaching or when we're giving presentations, we go back to. We revert back to that common experience that we have as children being in the classroom giving presentations, or those role models, right, those teachers that we saw stand at the front of the room and espouse knowledge.

What? Well, the thing is, is those types of techniques don't work with adults. And so, it really takes a different approach. And so, when I think about teaching adults, it's really thinking about what's important to them. You know, they want to learn things. Even just think about things that you approach today.

You know, you're interested in your hobbies, you know, something happens at your house, and you want to learn how to fix it. And so oftentimes, the way we come to learning with adults is different.

We, when we think about children, it's more sequential. We box things right in subjects. Adults don't learn well that way. And so, the best way that they learn is coming up with things that are relevant to them, things that are timely, things that they need.

They want to be interested.

Oftentimes, too, adults will consume as much information as they can.

Just think about, you know, maybe a time that you wanted to improve a golf swing or you got a diagnosis that was new to you, and you went out, and you rent everything you possibly could and how to change your diet and so on and so forth.

So again, adults are different in how they consume information and how they process information.

The other thing that I would say is important too is that by the time we get to adulthood, we have a lot of experience.

And so, when we take in information, I tend to think of how we think.

I follow a thinking about learning called schema theory. And so, we take in information, and we figure out, and we look at it, and we say, okay, how does this fit in with the scaffolds of knowledge that we already have?

How does this fit in with my existing experience?

And so again, it's, you know, when they're learning new concepts and new information, they're taking that in. And as someone that's educating them, you really have to understand what perspective that they're bringing, because you may have to override that.

You may have to shape that so that they get to the end goal that you're intending for them.

Etienne Nichols: In the medical device industry. Because I'm just thinking about applying some of the things that you're saying.

In the medical device industry, it seems like it's a tradition to break the spirit of a new hire by dropping 40 sops on their desk. On their first day for them to read and understand.

And, and I've done. I've gone through this experience multiple times, and as a manufacturing or regulatory or product development engineer, the different roles that I've experienced. And you read and you understand, you fill out a quiz and then it's like, gone.

And so, I, I wonder, are there, if you were to.

Do you have any examples of how applying this, it breaks the system.

Dr. Shannon Decker: For the sop?

Etienne Nichols: Well, I'm just thinking of maybe, maybe examples of, of wrong ways of training that we typically fall back on and right ways and maybe better ways to do that.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Yeah, so there's lots of ways I think I can go with that question. But it's a great question. And you talked about medical devices, and I have a lot of experience doing that in putting out medical devices and making sure that physicians are using them.

And I can share some of those experiences of what was happening before and then what happened after we had done our implementation.

And so, I worked with a very large medical group.

We had over 800 physicians.

We covered in total across Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, commercial, close to, I would say, 750,000 lives.

So quite a few.

And at that time, our vendor, when I started there, the medical device company, one of them that we were using was just handing out devices.

And I was like. And I was looking at the data and trying to understand why the prevalence of disease capture in a particular area was as low as it was, because knowing that we were putting out these devices, it should have been more in line with what we would expect with the population.

And it wasn't.

And we also weren't seeing, you know, we could tell when people were plugging in and, you know, whether or not they were using the device and getting some of that data back.

And when I spoke to the vendor, you know, they had shared with me, they said, well, you know, we don't really provide any education, or they can go on, and they can watch a video.

I know a lot of those tech vendors like that, you know, they figure if they put a video out there on YouTube and that's all well and good, but really, when we think about adult learning, there's a few things that need to happen and a few considerations. We learn in different ways.

And I think one of the things that we know about adults, too, is that they need that tactile input. In fact, when we think about learning, and I can talk about a lot of different things, but we think about auditory, visual, and tactile inputs in order to take in information into process.

And those things resonate well with adults, too. And so, in this instance, again, you know, devices were handed out.

Doctors didn't use them.

And what we did to change that, to bring in principles of andragogy to make sure that they were using the device, we did a few things. We said to them, hey, we have this great device. We showed them their results. And so, I think a lot of times showing them what their performance is.

So again, it's revealing something to tackle, right? And so even with that new hire, rather than SOPs, put them in a project team and let them work on something.

And so, the same thing here. So, sharing results with physicians about how they were doing and how they were doing compared to their neighbors was really motivating to them. In fact, oftentimes getting a lot of concepts here, but oftentimes intrinsic or that internal motivation has a stronger pull than what we think about extrinsic motivation.

Right, which is typically things like money. And so, we all want to do well. And so that was a huge motivation for them.

Other things that I said to them was, I'm going to be monitoring how you're using this. I know what your patient panel is, and I would have an expectation, because you have this many and at the time it was senior patients in your panel, that you should be testing X amount of times.

And we would watch for that. And so, by providing that feedback, it did a few things, right? I could call them up and say, hey, I noticed that you're not using your devices often,

as I would expect, given your panel, has anything changed? And I'd find out, you know, someone left the office, the person that did that piece no longer was there. And so, we would have to go in and do that retraining.

But that's another piece that's important to adults, is really getting that feedback and not on a regular basis. Because if you tell them it's coming at certain times, right. They expect it.

It's good to watch and to give them feedback in a way that is not as expected.

And again, that'll be important to guide behavior.

Other things that we did is we called them in, we provided dinner, or we'd go to the office, but we'd sit down with them, and I'd say to them, okay, I want you to actually use this device. And let me ask you, I know I have this challenge, you know, who reads the book in trying to put things together or to understand instructions, I can tell you behind me, I have a lot of camera equipment, and I'm still trying to figure out how to use it, because I hate reading the book.

And the same thing, right, for our physicians and for others, other adults that we're working with.

And so, the best thing that you can do is to give them multiple sensory inputs, especially tactile practice.

And we would hold dinners. That's the other thing, too. Adults like to learn in groups so that colleagueship is important.

So, we brought them together at a dinner and we said to them, bring your devices. And let me tell you, that's when the truth came out. They brought me spirometers that had been in a box for five years. The dust was thick on it, you know, you were coughing and sneezing.

And they brought the devices in, and we actually said, okay, we're going to have a practice session. And that's the other thing, too.

Around technology especially, people need to see how it's useful, and they also need to feel confident as users. And so, we gave them that tactile practice. And so, they sat around the room, they got to test their friends.

They brought people from their office. When we were in the office, we brought everybody together and they had an opportunity to actually use it. And what we found in a bunch of different situations, there were instances where, and I know you're going to be surprised, and these are super smart people, but we all do it right. Didn't have the battery put in use too much jelly. So, the conducer wasn't working.

All sorts of different things that made it, so they didn't feel confident as users. You know, it was that getting over the hurdle of getting it out of the box and actually putting it together and then finding that it was useful and then again giving them that opportunity to practice.

So, all those things are really helpful and tap into what it is to work with adults and why it's so important to think of them differently and really think about your audience as opposed to teaching in a way in which you were taught.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, so I kind of think categorically, or I like to categorize things. And we talked about a few different areas where this could be applied.

I'm thinking of, like, technology development, when you're developing the device, when you're selling the device, and then actually adopting, which is what I think we spent a lot of time on, which is super important, is adopting that device and actually getting them to use that.

But maybe before we go into each one of those categories, can we talk a little bit more about some of the principles of andragogy?

Specifically, if you're able to tell me where it might be in somewhat opposition of pedagogy, I'm just thinking like, okay, a child might learn this way, and we want to revert back to teach people the way we always taught as children.

Are there any things that are almost the opposite or anything kind of like oppositional to that way of thinking or teaching?

Dr. Shannon Decker: Absolutely.

Usually when we think about children in the way in which we teach, you have someone that's guiding the learning. Adults guide their own learning.

So, they're going to. It doesn't matter. And you can think, just even in general about organizational change.

You know, you have people that are going to approach it differently. No matter the message you get out, you might think about. And just to give folks an example of a memo that you've put out, or maybe you've said something in a meeting, you've reiterated something time and time again, and then you're confused as to why other people, you know, the audience came away with different messages, even though you spoke the same words in the same way at the same time, you know, to that, that whole audience.

And so, they're going to come to learning in a different way.

The way children typically learn is they are directed. And so, you have someone that is determining what their learning is going to be.

And usually the construction of the content, too, is sequential, where when we think about adults, pieces are being pulled in as needed as they need to learn. And just think, too back to a class that maybe you took in high school or even elementary school.

Think about science.

You learned about science sequentially.

You learned about cells, and you learned about the functions within cells, and everything was planned for you and the order in which you were going to learn it. And you had to master that skill before you moved on.

What's different about adult learning is that oftentimes they don't need someone standing at the front of the classroom. Right.

They need someone that will facilitate them and say things like, you know, after they run out of places to look for information, go look here, or did you think about this? Or did you check this?

And their own motivation will drive them to find other sources and then in how they consume information.

When I think about pedagogy in teaching of children, it's the textbook, it's sequential, it's guided.

Whereas with an adult, it's guided by what they feel internally that they need to know.

They'll pull in information.

They may look over here and then look over there. As far as in pulling information, um, it's not going to be what somebody's Told me I need to learn, but rather whether or not they're motivated to learn it. And so, they really have to understand what's in it for them, because those are the things that they'll pick up.

And, you know, you mentioned about development or even, you know, adoption. They have to understand what's in it for them and how, you know, how it's going to be useful for them.

Etienne Nichols: Well, I'd like to dive a little bit deeper on how to apply this across these different, maybe three different inflection points. But I can 100% identify with what you're saying, because I can point to a time where I was going to be an event.

I do not play piano, but I thought, you know, there's going to be a piano there, and I could get everybody's attention by just playing a really quick blues riff or something, just for like 30 seconds, just really.

And so, it didn't take long, but I thought, okay, the, the. The problem I want to solve is I want to get everybody's attention, get them entertained, and then I could launch into my presentation.

But. But I'm just going to play this piano. So, I just learned it. I spent like, I don't know, half an hour. And I just, just so you might think that I play piano based on that, but I only learned it to get the attention of the audience in that moment.

So, I don't play piano, but that was a problem I wanted to solve.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Well, and that's fantastic, too. And think about, too, the energy that you expended towards that. Think about, you know, do you have those times if you think back to your experience as children in schools?

Right.

Oftentimes the impetus for learning was given to you by someone else. You brought that and had the passion and the desire and then also too invested that time specifically for learning that skill.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah. Yeah.

That's interesting.

I don't think I've ever made the connection between the learning of when I was younger versus what drives me to learn now. So that's. That is very interesting. How can we apply this to the development of a device?

Because when I'm developing a. We talk about human factors and solving the problem, not just focusing on the technology, but what are some, some specific actions we can take when we're developing a device.

Dr. Shannon Decker: I think talking to the audience, talking to the users, a lot of times we assume we know or. And I'm, again, I've been a part of implementations and have worked with a lot of technology, with physicians specifically, over the last 26 years.

And what I found is, is that, you know, a lot of times you would get great technology and folks would bring in and say, look, what I developed, isn't this great?

And they would try to sell it to the physician. And that really is a backwards way of thinking about development.

Or maybe, maybe it's forward and you need to think backwards.

You really need to think about, you know, who your users are and develop to solve their problems.

You know, really get to know what it is that's important to them and build out from there. You know, the old adage, if you build it, they will come, they won't.

And so, you really need to think about finding things that physicians, if you're thinking about clinicians, but it could be any audience in any market that you're working on.

But find out what it is, you know, that challenges them, that either drives inefficiency, keeps them from reaching whatever motivation is that they have.

And if you can tap into that and then build out or even build your messaging right around that, you're going to have much greater pickup and adoption and a much more, again, accepted product that people are going to be open to using.

Because think about it, when you are developing a new product and you're handing it to them, like in the instance when I gave those positions, you know, different medical devices to go and use, had I not shown them how to use it, had I not given them those opportunities to practice, had I not shown them how to fit it into their workflow and given them feedback.

So, I'm constantly giving them reinforcement of how they're using it.

They never would have used it. Right. It would have been too difficult for them to understand how it fits into what they're doing.

And so, again, I think you really need to have that in mind whenever you're developing any tool, start with a challenge or something that they're trying to solve for and figure out ways that it can fit in to how they're currently working.

You know, that's another thing, too, with adults. You can't ask them to go from sitting on the couch to running a marathon. You have to give them time to get ramped up.

And so, again, if you're developing slick tools, you have to remember that it can't come in and totally upend everything that that clinician is doing in their office.

Or at least you have to make the process.

You have to guide them along that process so that it doesn't feel like, again, you're totally flipping the table and they're having to, you know, undo everything that They've done before it can be done. It's just really difficult.

And again, I know I mentioned it earlier, that's the other thing too, is that when you're working with adults, they're bringing a ton of experience that you with your new device are coming up against and trying to convince them that they need to use that when they have all this other life experience that they've gone through that's telling them, you know, that they've been doing it right for so long.

So those are some of the things that I would take into consideration when.

Etienne Nichols: I think about that adoption, because I really like that idea. I had a mentor tell me the heart of the problem is the seed of the solution. I don't know who originally came up with that, but.

But the idea that you really understand the problem you're trying to solve, the solution usually just presents itself.

And if that's the case, and if we're thinking about how to get someone to adopt this while we're in development, we think about those intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

For example, the ability to see when someone uses the device and keep an eye on those different things, or the ability to monitor that and compare it to another clinician office so they under have an idea or a benchmark to compare themselves to. I almost think of like the competitive part of a physician might come out and say, well, I want to be, you know, I don't want to be average.

I want to be above average. What are some tips and tricks you have in thinking through what and. Or finding out what those motivators are so that we can build them into the product and really take advantage of that?

Dr. Shannon Decker: Sure.

So, one of the things that I would recommend is make people part of the process.

If you make them part of the process and they participate, then they're more likely to come along.

And so early on, and I know that we think we do that, but really make them part of that project team and listen to their input. When they give you input, don't dismiss it and think that you have a better tool.

Really listen to the feedback that they're giving you.

You mentioned intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. And I'll just share with you.

I have been.

So, I conduct my own research, and I've been doing this phenomenological study, talking to physicians about their experience in medicine, how they went to school, what they thought medicine was going to be like for them, and then their experience since getting out of school, now that they're in practice, and then particularly focusing in on how maybe Covid may have changed that for them.

And even though we're out of COVID Right. How those effects still linger. And one of the things that I can tell you, so I've interviewed 37 physicians thus far across the nation, primary and specialty, so an equal mix, different ages. But I can tell you what every single one of them has said to me, which is one of the reasons why I wanted to take the study up, was that they went to school because they wanted to help people.

And if you can appeal to that motivation.

And those are the things when I go out, and I talk about new programs that I have, and I work a lot in value-based care.

I don't talk about the money that they're going to make.

I don't talk about the administrative burden or how the government needs this data.

What I talk to them about is by paying attention and doing these screening exams, you're going to have an impact on the overall health of your patient.

And we know, and I'll just give an example, I use this a lot.

Diabetics, we know that their eyesight is impacted usually within the first year of receiving a diagnosis, definitely within the first three years.

And to the point that if they don't have it under control within 10 years, there's significant vision loss.

If I say to them, you know, oh, make sure that you use this diabetic retina, retina camera to perform the retinopathy exam that they're supposed to get every year. And isn't this a great piece of technology not motivating to a physician? If I say to them, I'm going to pay you $25 for every test that you conduct or $100, there's a few things wrong with that.

It's a slippery slope because $25 might work for someone and then that might not mean anything to anyone else, right? They want 100. And over time you're going to keep incenting and then you really divide, right. The behavior that you want from that reward that you're giving.

And just think, I'll leave you with this too. Think about all the gift cards that you've received in your lifetime and, and I don't know about you, but I've lost them, they sit in my wallet, I forget about them, right?

So, it's really not something that is a strong encourager of behavior. Or even if I said to them, oh, the government requires it, think about when you've been told you have to do something that you don't want to do, or it adds to your day.

And it just seems burdensome. Right. You're fighting it tooth and nail, pushing up on it. You don't want to do it.

But if I say to you, here are the statistics that I know about diabetics, and this is what I know, that happens. And so, you have to do this exam every year.

Those are the things that will motivate that physician to want to do those exams because they believe.

Right. That it improves again, improves health outcomes, improves the lives of their patients. And so those are the things that I think that you really need to think about.

Etienne Nichols: That's an interesting study that you're. You're performing. And it's encouraging to know that that's the motivating or the driving factor for a lot of people that go into med school, as far as being able to help those patients.

I would be interesting. Yeah, go ahead.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Well, I was going to say think about the sacrifice, the hours putting off. Right. Possibly family, the hours that they're spending studying, the money that they're spending towards school. It has to be for something greater.

You reminded me though, too, and I wanted to share this with you and about the competitive spirit of physicians. And that's true.

So, some other behavior science that I can espouse to you a few things.

So, think about when you're trying to get technology out there.

There's something about this principle of diffusion.

Don't look for the loudest musician in the room.

Think about those that are influential. And so, when I would look at setting up programs, I wouldn't look for the doctor that had the biggest practice or that spoke the loudest in the room.

I would look for those on the periphery that had a strong influence, that were well respected in the community.

And I would go and talk with them, and I would work with them and make sure that they had a positive experience.

And when they did, they would share that information.

The other thing I would say, too, is along that same line, don't always think about focusing on low performers.

Also, you have to remember that some of the people that are easiest to move and where you can get the most traction are going to be in the middle of that curve.

Right. Or even at the end. We want to keep reinforcing those that are doing good work and giving them pats on the back. They need that reinforcement not only to keep up.

Right. And keep doing what they're doing, but also to. They provide a model and example to others that will eventually come along. When we think about adoption curves, right. That I know a lot of you have learned about in order to, you know, there are those late adopters or those low performers.

Instead of focusing your energy there, focus on the middle and the top part of your curve, and that will encourage those low performers, or it should, anyway. You'll get less and less of them, and it will slide that curve just a little bit so that more are coming along.

And I'll give you one more.

I can remember sharing results with physicians. I was at a physician dinner, and I would put up a grid, and people say, oh, you don't want to call them out?

Baloney. They want to know. But even if you blind it, they're going to figure it out.

And in this instance, I did blind it. I didn't put their names. I just put how they were performing.

And in that instance, I also chose the company that I was working for. A large healthcare company wanted us to focus on the revenue. And instead of that, I chose metrics.

I included that one because it was important. It was part of my job. But I included other metrics, too, that I knew would be important to the physician. Like, hey, I know that of all the conditions that this patient has, you didn't document them all.

And we know that this is important for XYZ. So, I came up with five or six additional KPIs that I wanted to talk about that were important.

And in the end, those. Those metrics actually got at the revenue. Right. But instead of leading with the revenue, I talked about the things that were important for health that I knew would appeal to them and would also speak to performance.

And they mattered, and they tied into the motivation that they had.

I didn't have their names, but I put gold stars next to all those that were performing.

And let me tell you, I had people chasing me around the room at the break after, you know, later in the evening, wanting to know how they, too, could get a gold star. And they figure out, just like we did as kids, right.

Who was in the Red Robin reading group versus the Bluebirds or what have you.

They can figure it out, too.

And they wanted to know how they, too, can, you know, could get a gold star. And so, again, I think that those are things, you know, that you can be thinking about as you're thinking about learning and technology adoption and trying to change behavior.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, there's some things that probably don't ever change.

I want to know how we fit into the overall. Yeah, that's interesting. And no, I mean, you. You mentioned a couple things there that I think are worth highlighting.

I think of when you talk about going to that. Well, respected. Maybe he's quieter, but he's clearly respected in the industry. I think it's. John C. Maxwell has that 21 irrefutable laws of leadership, the law of respect.

Those people follow leaders stronger than themselves or those who are more respected than themselves. And I think that's valuable.

The gift cards. I've never heard anyone else call this out, but there's a book called Giftology by John Ruhlin, and it's one I recommend. It's a short little reader. Um, but in that, I kind of learned a little bit of what you're saying as well.

I have my team. Sometimes they want to bring up gift cards, and I just tell them that's kind of like a homework assignment. I. I mean, if it's big enough, sure, you.

Maybe you've motivated someone, but I'm the same way. And so motivating people in those different ways, that's. I think that's valuable and worth emphasizing.

Dr. Shannon Decker: We would. Well, and I can tell you, too, in this.

In this instance of this program, in addition to calling out the physicians, you know, that were making a change or a difference, we also looked for leaders or champions within the medical groups. And I was working at the time; it was with 16 different IPAs.

And just to that point, we would. We gave them a stipend for the extra work that they were doing.

But we looked at things like how they were motivating. It wasn't just top performers.

It was those that maybe had the greatest growth. And so, we came up with other things to reward that would encourage that behavior. And also gave an opportunity for more people to participate.

Right. So that they felt like they could have a stake in it, too.

We gave them the title of associate medical director of you know, clinical quality.

And I gave them a really nice trophy. It's this big crystal trophy that they could set in their office, and then we would present it to them in a dinner in front of their peers.

And that was huge.

That was really touching and meaningful to a lot of them. And so, while the stipend, you know, the additional monies were important, it was an outward display of appreciation and of patting them on the back. Right. And acknowledging the work that they had done.

And, you know, to your point, the gift card is the homework assignment. Now, you gotta go out and use it. You gotta remember that you have it.

But if you say to someone in a meeting, hey, I really liked what you did, and you have to be specific.

That's the other thing with adult learners. You have to be very specific and name the, you know, name the behavior.

So, I really liked when you did this. And then this way they remember and it's repeatable.

Etienne Nichols: I kind of go on a limb here. This might be a little off topic, so feel free to punt if that is. But what about culture? Does that. Have you. Have you seen any culture differences in how all this can be applied?

Dr. Shannon Decker: I haven't. However, I would say that there are intersections where culture does impact.

And so, depending on age, depending on gender, depending on race and ethnicity, it can have an impact.

There are certain cultures that are taught, and I'm thinking particular race and ethnicity that are taught to respect or to treat like you were saying, you know, an authority figure differently. And so there may be different ways to appeal in that way.

So just, again, be thoughtful.

But I can tell you I've gone into a lot of physician offices in Southern California.

And, you know, if you've been to Southern California, you would guess that most of those physicians are of a different race and ethnicity than I and still was able to command respect. And I think that some of the things, when I think about those types of interactions that bring in what I've said previously and maybe expand and pull out some of the nuances, I would say always enter or come from the standpoint of, you know, you're there to help and you're there to listen, don't speak over someone. And so, I would always go into an office and say, tell me how I can help you. Where are you having challenges? And I think that that's something that's universal.

It may take a little longer, you know, depending on, you know, the level of respect that you have, but it still was effective.

And then the other thing I would say, too, is make sure that you prepare.

Don't go in there not having the data that you need. And when you don't have it, though, so here's the thing. If you don't know the answer, greater respect if you say that you don't know, but you'll get back to them and then get back to them in a timely fashion so that they're, you know, they're not left hanging when you're asking.

And that's something else that I would say when you're asking someone to make an investment in you, because that's what you're asking, right? When you're putting out those devices, it's homework.

They have to learn how to use it. They have to figure out how to incorporate it into their practice.

If you ask them to make an investment in you, you need to make an investment in them as well. And so that means not going into the office hurried. Yeah, donuts and things like that may help, but again, that's extrinsic motivation.

You know, it might get your foot in the door, but it's not going to. No one's going to remember the great box of donuts that you brought them. You need to have a more lasting effect.

So go in there, you know, maybe a few times over a time period, but make sure that you're willing to listen and then really listen. Right. And don't think that you can apply your understanding over theirs because you're not at any more of a privileged place than them.

If anything, that you're less.

And then understand, you know, what their issue is and try to solve it. If you say that you're going, you know, you promise something, you better deliver and deliver within a timely fashion so that they remember that you made that promise to them.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that's really cool. I like the.

The good application and the way to do that. So, I'm going to flip it a little bit.

When I was in manufacturing, they taught us all these different Japanese words like kata and kaizen and pokyo gemba.

There's one that they didn't teach me, but I recently heard, which was hanmen kyoushi, which is the opposite aspect teacher from whom one learns what not to do. And I wonder if you could tell us any.

Any things that. Now this seems to be the way a lot of companies are trying to get their technology adopted. And these are the mistakes they make. These are the pitfalls.

Any thoughts? There's.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Well, that term is new to me.

Etienne Nichols: It's okay. It's a Japanese term. Probably never.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Yeah, no, but the concept. The concept isn't.

Yeah, I would say so. It makes me think of a couple of things. One would be that it's very difficult to unteach, to unlearn bad behavior.

So, if somebody's learned something that is inappropriate or, you know, isn't incorrect, you know, we've proved that the world, hopefully no flat Earthers listening. But, you know, if we learned that the earth was flat, it's very difficult to understanding that the earth is round.

And you have to work twice as hard to unlearn wrong thinking or wrong learning.

When you use the opposite to challenge someone, I think it can be very powerful.

And I go back to. We're talking about words.

I have to remember this a long time ago, when I think about learning, it comes from the Latin word educare, which means to care.

But when we think about care, it's really. It's about causing strife when we go back to the actual meaning of the word.

And so, you know, you make me think of the opposite, because when you create that friction, right, when you. Or that dichotomy in the mind, it's more likely to be a disruptor.

So, I think it could be really positive. I think of ways, you know, that maybe are opposite, some things that you might show.

Trying to think of an example, the one I can think of that I think would fit here would be working with a physician once in their EMR and helping them set up a template within their EMR to do the PhQ2 and PhQ9 assessments.

And what we did is we found out that they were doing it in one particular way.

I don't know that we could necessarily make it harder.

I don't know, maybe it doesn't work.

But anyway, it was an opportunity to demonstrate one way in which things were being done versus another and then pointing out the inefficiencies.

And I think that, you know, if you can do that, but that is a very powerful tool if you're able to identify that and share with them, you know, based on whatever.

Whatever technology it is that you're trying to get them to adopt.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, that is interesting. I did not know the root of education, and that's interesting. And you talk about that. Conflict versus peacemaking. I don't know if you ever heard the phrase peacekeepers avoid conflict to maintain the status quo, while peacemakers embrace conflict in the pursuit of peace.

I always like that phrase, you know, peacemaker versus peacekeeper.

Dr. Shannon Decker: I have not heard that, but I agree with it 100% and definitely think that that is spot on. So, thank you for sharing that.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Any other pieces of advice or thoughts that would be helpful for the audience when it comes to this different type of. Of teaching? Really bringing people along to.

To approach. Approach teaching in the way that adults can actually embrace it and truly apply it. Any. Any last thoughts?

Dr. Shannon Decker: Just a. A couple of things I know I mentioned about the different modalities. If you want to encourage adoption and, and greater depth of experience and learning, you know, think about visual, auditory, and tactile activities so that touching.

Right. We don't just need to see things; we might need to hear it too.

And everyone has a different learning style, you know, and I'm sure the audience will say, yeah, I learned better by doing. I'm that type of person.

Not everybody is, though. Some People learn by seeing, some people learn by hearing.

And so do provide different opportunities for the different learners that you have out there.

The other thing is, though, is by tapping into the different senses, you create a more enriched experience.

And so, you'll have a greater opportunity again for use in the way you want.

The other thing, I would say a couple more things.

Think about what it is, what behavior you want folks to demonstrate, and then make sure that you teach in that way and that you support in that way.

So, a lot of times, and I use the story of, you know, the driver's exam, if you read just the book, you don't know how to drive a car, you actually have to go out and practice. Right. And so, when we think about driving a car, you need to go practice.

I understand you don't have to do this in all states, but I had to, you know, do parallel parking and the K turn and, you know, demonstrate that you're not going to get that by reading a book. And so why do we expect, you know, our physicians or others to know how to operate a machine if we just give them the manual? And so again, you have to give them opportunities to practice.

And there is something about knowledge if they're, you know, if you're interested, I always think about Bloom and Bloom's taxonomy and the cognitive levels that we go through when we're learning information.

And so again, if you want someone to perform, say, at. And a level of evaluation, you know, you can't just give them a manual to read, which only taps into them working at, you know, comprehensive levels.

So those would be some things. So, think about who it is.

Envision who it is that you want at the end. What do you want that position to look like using your technology and then work backwards? What are all the things that you need to do to get them there?

And understand too, because again, those adult learners understand the experience that they're bringing to it because there may be opportunities to tap into that as well. And not everybody in your audience will be the same.

So, understand that the needs of someone, the front office staff, may be different than the physician. But also, too.

See, I have a lot to say.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Also, too. Don't discount any position that anyone in that office has.

Everyone will be important to contributing right to the adoption and the use of any device that you're putting out there.

Etienne Nichols: Oh, yeah, I think that's a really wise thing to say. My wife is a nurse and she; she has lots of stories about the nurses really making things happen or not making things happen. So regardless of where you are.

Yeah, you may actually, I. I know I said that was the last thing you made me think of something on the fly. So, I'll just throw you another curveball that you can feel free to ignore.

Holding into the recesses of my mind when you were talking about the way that people learn, I think when I was taught early on it was something. I think someone used the phrase auditory, visual or kinesthetic use, tactical.

And are there tricks to knowing how someone learns better? I was taught that the way someone talks might be an indicative. If they talk really, really fast and they say, I see it this way and this is the way I have to see it happening, then you know, their visual.

If they talk slower, it's more auditory. And then I feel like you get into that kinesthetic. I don't know if you have any thoughts or tricks.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Um, so kinesthetic tactile. I mean the same thing. I'm using them synonymously. Um, I don't know of recognizing the differences. I've just always provided all those experiences in any learning that I was doing.

And even though, and this is what I would say too, even though someone might be a kinesthetic learner, right. Or. Or learn through touch, it doesn't mean that you shouldn't still reinforce using other modalities. I think it's important to bring a balance of the three.

You can certainly. And as an adult learner, again, right, you're going to choose your learning style. Some of us are going to go watch YouTube videos, some of us are going to listen to a podcast.

Some of us may sign up to go to a conference.

There’re different ways or different inputs and information that we're going to look for.

Some of us prefer reading a book versus listening to a book on tape, but it doesn't mean that while you may have a preferred modality that works for you, I think it's still important to try to tap into those other senses because again, the more sensory input, you know, you had mentioned about, you would learn things and then you discard it.

When you read those SOPs, if you want someone to really understand those SOPs, have them not only read them, have them, teach a lesson on them, have them, highlight them, have them, you know, use all those different skills and by manipulating information in more ways.

Because that's another thing too, if you want, you know, there's a reason why we have commercials and are presented so many times to people and why we have to do that or why billboards can be so effective.

Is because we need to have people presented with information multiple times.

Usually there's a number to it, it's five to eight.

And so, if you provide five to eight experiences to someone with content or with information, they're more likely to hold onto it.

And it transfers from short term to long term learning.

And the way in which you do that is by creating these multifaceted experiences by again tapping into our different senses. And you know, we said kinesthetic or tactile, auditory and visual, but there's other things that you can do too. You can use olfactory, right? There may be scents and smells and things like that or taste that you can add in there as well that would help someone again consume and hopefully master information.

Etienne Nichols: Yeah, yeah, that's really interesting. I, I might even be interested at some point. Maybe we'll have to talk about the additional, like, I don't know what you would call them, feelings of sadness, anger, et cetera. I mean, because it seems like there's some elements that you could bring out there as well to even heighten the aware. So in addition to the physical tactile.

Dr. Shannon Decker: 100%, the anger piece goes to what, you know, kind of what I was saying about the educare and the caring and the creation of conflict or what you were saying about the opposite.

So, our emotions absolutely can have an impact. And a lot of times when we're in that state, think about that. And even like studying for an exam in college or how we learn today as adults, if we have the pressure of, you know, our spouses yelling at us to fix the leaky faucet, we're motivated right by that angst to go out and learn as much as we can. Or our boss, we know we might get fired if we don't learn how to sort in Excel.

Whatever skill that it is you're trying to learn, those types of things can definitely influence how you're learning as well as influence your motivation for learning.

There's definitely some shaping that's going on in the mind around that.

Etienne Nichols: Well, I know you have research going on now and all the different things that you're working on. Where do you recommend people go to find you? We'll put links in the show, notes and so on.

But if people want to just go find you, if they're driving in the car, where do you recommend to go?

Dr. Shannon Decker: I really appreciate that you can find me on LinkedIn.

I have a pretty good presence there.

I actually publish my own podcast specific to Value Based Care and usually launch it there. I do have a YouTube channel as well, but most people find me on LinkedIn or you can find me at my company,

www.vbcone.com right?

Etienne Nichols: Awesome. And we'll put links to that. It's always great to have another podcaster on the show and but I know we're close to time, so I'm going to let you go.

Those of you been listening, thank you so much for listening to the Global Medical Device Podcast. Shannon, thank you so much for all your insights.

Really appreciate you coming on. We hope you all enjoyed the show, and we will see you all next time. Take care.

Dr. Shannon Decker: Thank you.

Etienne Nichols: Thanks for tuning in to the Global Medical Device Podcast. If you found value in today's conversation, please take a moment to rate, review and subscribe on your favorite podcast platform. If you've got thoughts or questions, we'd love to hear from you.

Email us at podcast@greenlight.guru.

Stay connected for more insights into the future of MedTech innovation. And if you're ready to take your product development to the next level. Visit us at www.greenlight.guru. Until next time, keep innovating and improving the quality of life.

About the Global Medical Device Podcast:

.png)

The Global Medical Device Podcast powered by Greenlight Guru is where today's brightest minds in the medical device industry go to get their most useful and actionable insider knowledge, direct from some of the world's leading medical device experts and companies.

Etienne Nichols is the Head of Industry Insights & Education at Greenlight Guru. As a Mechanical Engineer and Medical Device Guru, he specializes in simplifying complex ideas, teaching system integration, and connecting industry leaders. While hosting the Global Medical Device Podcast, Etienne has led over 200...